| Globally, millions of children suffer from vaccine-preventable diseases. The significant majority of them are from developing countries; nearly one million children miss their childhood vaccines only in Ethiopia every year. A cross-sectional mixed study was conducted in the north Shoa zone of Amhara regional state in Ethiopia to assess factors affecting childhood vaccination coverage.

A total of 371 caregivers were included, and 80.3% of them were female. Twenty caregivers were purposively selected for an in-depth interview. The quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and logistic regression, and the result was interpreted based on OR, AOR, and p-value at 95% CI. About 218(59%) children were found fully vaccinated. Childhood vaccination status was found to be affected by caregiver knowledge and awareness, such as an awareness of where to get the vaccines AOR 0.33[0.12, 0.9] with a p-value of 0.003, and knowledge of when to start vaccination AOR 0.23[0.11, 0.47] with a p-value <0.001 at 95% CI, being aware of the vaccination schedule; those who can easily recall the next schedule was 7.46 times highly likely to fully vaccinate their children, [3.04, 18.35] with p-value <0.001. The sociodemographic variables were also found to have a significant association with full vaccination status; distance from the health facility between one to four kilometers AOR 0.2[0.07, 0.58] with a p-value of 0.003 and from four to eight kilometers AOR 0.24[0.08, 0.71] with p-value 0.01. Caregivers’ pre and post-health facility visit experience also had a significant association with full childhood vaccination status; hearing peers complain about vaccination service AOR 0.33[0.16, 0.69] with a p-value of 0.003 and those who didn’t receive advice from a health professional on the next vaccination schedule, AOR 0.35[0.12, 0.99] with p-value <0.001. Vaccine promotion had a significant association with childhood vaccination status; caregivers who strongly disagree on the adequacy of vaccine promotion AOR 0.21[0.05, 0.86] with a p-value of 0.029. The qualitative study findings also complement the result of the quantitative study. Moreover, the finding from the qualitative and quantitative study agrees with the desk review result; the gap analysis in the Ethiopian Health Sector Development plan and Immunization Strategy reviews as well as the weakness of the Ethiopian Health Extension Program. To solve the gap identified, the study recommends that the North Shoa Zone and Amhara regional health bureau work with its partners to increase the knowledge and awareness of caregivers and improve access to vaccines and service delivery strategies. 1. IntroductionVaccines are the most important public health discovery in human development. The term vaccine derived from the Latin Variolae (cowpox), which Edward Jenner demonstrated in the second half of the 1700s, could prevent smallpox in humans.(1) Currently, the term vaccine refers to all kinds of biological preparations which can be prepared from living organisms that can enhance immunity to prevent disease or, in some cases, treat disease. Vaccines can be produced and available for use in different forms. Besides the bulk antigen that makes us a certain vaccine, there are several ingredients that will be added, like water. The quality and potency of the vaccine also depend on the additives in the vaccine and other environmental factors. As much as possible, vaccines are formulated so as to be both safe and immunogenic when injected into humans. Vaccines are usually formulated as liquids but may be freeze-dried (lyophilized) for reconstitution immediately prior to the time of injection.(1) 1.1 Background and ContextDespite the discovery of more important technologies in vaccine and management; still, there are gaps that hinder vaccine delivery and achieving the complex immunization schedule where children will receive an entire course of vaccine required to be completed before the age of three years, and in most cases, in less than two years of age.(2) The presence of an effective immunization program in a country can help a country in saving the loss of economy for health care through early prevention of vaccine-preventable diseases. An analysis conducted in China on the measles vaccination campaign in the eastern province of Zhejiang, which provides one dose of measles-rubella vaccine at eight months of age and one dose of MMR at 18 months, estimated that for every dollar spent on immunization, the health system saved about $6.06 in treatment costing, including the cost of treatment complication and longer effect. (3) In the United States alone, nearly 103 million childhood diseases have been prevented due to childhood vaccination programs since 1924. In the US, an investment of one dollar helped to save three dollars from the payer perspective and 10 dollars from the societal perspective.(4) The economic benefits of the vaccine for developing countries are significantly higher than those in developed countries; a recent study conducted on the economic benefits of the vaccine in developing countries indicated that an investment of one dollar on vaccines in developing and middle-income countries would have an economic return of $44.(5) 1.2 Immunization in EthiopiaRoutine immunization started in Ethiopia back in 1980 with six vaccine-preventable diseases, namely measles, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, and tuberculosis. The initial target was to increase by 10% annually and reach 100% coverage by 1990; however, this target is still not yet achieved. Full immunization coverage varies from region to region across the country, where the highest coverage is in the Tigray region with 80%, while the lowest is in Somali and Afar regions with less than 5%.(6) After many years of attempts, immunization coverage stood at 71%, according to the World Health Organization and UNICEF estimates in 2018.(7) However, the full immunization coverage of children under the age of two is still not yet able to cross 50%. The immunization coverage in Amhara regional state, the region where this study will be conducted, is one of the lowest as compared to some other regions like Tigray and Addis Ababa. According to the EDHS 2016, the full immunization coverage of the region was 41.6% which is very far behind the World Health Organization recommendation; 90% of children should be fully vaccinated.(8) 1.3 Ethiopian National Health PolicyEthiopian health policy came into shape during the Degree regime that was mainly given priority to disease prevention and control through health promotion and basic curative services with a special emphasis on the rural community. This initiative was started through technical support from the World Health Organization. The initiative, however, was interrupted before it came to full implementation due to regime change, which was replaced by the current regime. The current regime revised the existing health policy to address ten thematic areas emphasising decentralization of services, improving preventive aspect of health care, equitablity, intersectoral colloaboration, etc. The revised health policy has indicated eight areas of focus and special emphasis on family health service, particularly on the health of women and children. One of the sub-area of concern indicated in the national health policy was expanding and strengthening immunization services, and optimizing access and utilization.[1] Despite a significant change in the overall structure of the health system, it seems the health policy is not yet attended to its goal of improving the maternal and child health sector, especially in terms of optimizing access and utilization as the full childhood vaccination coverage remains at its lowest point compared with the World Health Organization recommendation. It is important to evaluate its implementation from a different perspective, and as this study will evaluate the factors that contributed to the low coverage of full childhood vaccination, the finding will be used as an input to revise the policy on optimizing access and utilization of childhood immunization services. 1.4 The Ethiopian National Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI)The Ethiopian EPI is mainly supported by the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, and other partners like Global Alliance for Vaccine and Immunization (GAVI), both technically and financially. Other partners supporting the government of Ethiopia mainly come through these organizations to supply vaccines and cold chain management. The Ethiopian government has mobilized funds to cover the cost of BCG, TT, and 50% of OPV since 2009.(10) Immunization services are being provided in all health facilities, including both government and private hospitals. In public health facilities, routine immunization services are free of charge. In areas where the residents are outside 5 kilometers of the static health facilities, the immunization program is organized in the form of an outreach service. The Reaching Every District (REC) approach was piloted in 2003, and the finding showed there was a significant improvement on the DPT3 planned to scale up in another woreda where there are coverage gaps. This approach was mainly in use in areas where the immunization coverage was too low, like in the Afar, Gambella, and Somali regions of Ethiopia.(10) The existing immunization program document indicated that an advocacy workshop was conducted targeting regions like Gambella, Benishangul, Afar, and Somali regions to address the existing gaps and improve implementation. Despite the presence of leadership to implement immunization programs, financial problems and human resource gaps remain a big challenge in those regions. (10) 1) Problem statement and purpose2.1 Problem statementNearly three million children are dying from the vaccine-preventable disease each year, and the majority of this figure comes from developing countries due to lack of access to the vaccines. Whereas, people in the developed countries are showing complacency to vaccination programs which have impacted disease elimination efforts; for example, measles elimination in developed countries is affected by caregivers’ perception that as the “disease is no longer available in a developed country, a vaccine is not required.” This has caused a disease outbreak in the US recently; the case of a measles outbreak is an example.[2] A significant number of children are not getting a vaccine at all due to several factors like geographic inaccessibility, conflict, and other sociodemographic factors. Among those who started the vaccine, still, another significant proportion of children are missing the consecutive doses. In 2020, about 23 million children were missing their basic vaccination program globally; the data shows an overall increase in the total number of children who missed their vaccination program compared to the report in 2019.(12) The WHO report indicated that about 3.5 million children are missing their first dose of the DPT vaccine, and nearly 3 million children are missing measles first doses in the year 2020 compared to the year 2019 the same year.(13) More than 13 million under-five children live in Ethiopia; nearly one million children are missing life-saving vaccination each year.(14)(15) Studies show that almost 50% of children miss their childhood vaccination, and this varies from region to region and urban to rural.(16) Studies conducted previously showed that the coverage was even worse than the current one, in which as low as only 33% of children got fully vaccinated with high inequitable access to the vaccine. The vaccination coverage in Addis Ababa was seven times higher than in the Afar region.[3] The Ethiopian Health and Demographics Survey (EDHS) 2018 showed that the full immunization coverage of the country stood at 38.5%, while the Amhara region’s full vaccination coverage was 45.8%.(8) A quantitative study conducted in the North Shoa zone to assess factors affecting low measles vaccination coverage showed that the coverage remains at 71%, which is still far behind the World Health Organization recommendation.(18) This study was conducted in a limited area that cannot represent the other district situation, and also, its scope was limited to measles vaccination coverage which will be difficult to generalize for the general population when we talk about childhood vaccination. Generally, while vaccine remains the top solution for reducing child mortality globally, coverage of full childhood vaccination remains unsuccessful. The greatest challenge is found in developing countries, including Ethiopia. The area where this study will be conducted is one of the marginalized areas where road infrastructure and access to health facilities remain poor. In addition, the area is known for different cultural and traditional believe that affect childhood vaccination. 2.2 Justification of the studyConducting this study in the North Shoa Zone of Amhara regional state, particularly in Menz woreda in Ethiopia, will help to explore factors affecting optimum childhood vaccine uptake. The caregivers’ journey to immunization framework preferred to be used during this study to deeply understand what are the barriers at different stages for a caregiver to access full childhood vaccination for their children. Previous studies conducted in Ethiopia either lacked methodology or completeness; most of the studies were conducted to cover the quantitative aspect, while the qualitative remain very important to explain the quantitative findings and adequately support our inquiry. To the best of my knowledge, until this research proposal was developed, there was no study conducted to assess factors contributing to childhood vaccination coverage in the particular area where this study was conducted. Thus, this study will help to determine factors influencing optimum childhood vaccination. Besides, this study will be taken as a reference to study contributing factors for below optimal coverage of childhood vaccination in the future in the same area. 2.3 Purpose of studyThe optimal full vaccination coverage can be affected by several factors, including policies, environmental, societal, and family-level factors. On top of all factors, family-level factors, especially the role of caregivers, particularly mothers in the Ethiopian context, play a significant role. Hence, the purpose of this study focuses on assessing factors affecting the care givers’/mothers’ journey to vaccination, starting from deciding to vaccinate a child to completing full doses of a childhood vaccine. Hence this study assessed caregivers’ sociodemographic factors, knowledge and awareness, decision making and process of vaccination challenges, pre and post-health facility visit experiences, as well as the extent of vaccine promotion. The study was intended to assess these factors both quantitatively and qualitatively from the caregivers’ perspective. Moreover, the purpose of this study was to review the existing policies, immunization strategies, and other relevant guidelines and documents, including the Health Extension Program to link the finding from this research and show gaps with an appropriate recommendation to policy makers. 2.4 Scope of the studyThis study is a cross-sectional conducted from January 15 to February 15 to assess caregivers’ journey to vaccination using qualitative and quantitative methods in selected woredas of the North Shoa Zone. The initial sample size for this study was calculated to be 364, and it was adjusted to 400, considering a 10% nonresponse rate. The data was collected considering four different settings; urban, semi-urban, rural, and remote areas proportionally from selected woredas in the north Shoa Zone. Quantitative data was collected through a house-to-house interview using a semi-structured questionnaire, while the qualitative data was collected through an in-depth interview of 20 purposively selected caregivers among quantitative study participants. Besides the qualitative and quantitative study conducted through primary data collection, the country’s national health policy, national Health Sector Development Plans (HSDPI-IV), National Expanded Program for Immunization(NEPI), and National Health Extension Program (NHEP) were reviewed to link the gaps seen from the study related to the policy and strategies and provide appropriate recommendations. 2) Objective of the study3.1 Primary objectiveThe primary objective of this study was to assess factors influencing childhood vaccination coverage in the North Shoa Zone of the Amhara region in Ethiopia from the perspective of caregivers. This study used the caregiver’s journey to immunization framework developed by UNICEF and its partners to analyze individual, family, and health facility-related factors that can influence the decision of caregivers to fully vaccinate their children. The study was found to be the only research done in this particular area to assess what factors contribute to low coverage of childhood vaccination though the problem has existed for a long time. Hence, this study can be used as a reference for upcoming research in the field. 3.1.1 Specific objective

3.2 Secondary objectiveThe secondary objective of this study is to review country documents related to immunization and provide recommendations for improvement based on the study findings to improve the policy and strategies in the future targeting childhood vaccination. 3) Statement of hypothesis and research questions4.1 Statement of hypothesisThe overall childhood vaccination coverage in Ethiopia is one of the lowest, and full childhood vaccination coverage is the worst, which remains less than 50% nationally. Considering this fact, the researcher believes that the factors contributing for unable to attain full childhood vaccination or optimum childhood vaccination coverage need to be well studied especially in the area where this study will be conducted. The researcher believes that the absence of a previous study in the area has created a gap in policy development and implementation of immunization programs. The researcher believes that a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods will help to explore adequate information on why attaining optimum childhood vaccination coverage remain challenging. Besides, the researcher believes that reviewing the existing national health policy and providing feedback will help fill the gap and revise the existing policy to improve the implementation of the childhood vaccination program. 4.2 Research questionsThe research question address one main question, which deals with the factors contributing to low childhood vaccination coverage, and the second question shows how low childhood vaccination coverage can affect policy development and implementation. Question: How the caregivers’ journey to immunization will be affected by different factors in vaccinating their children during childhood? Furthermore, how the national health policy development and implementation be affected by low full childhood vaccination coverage? To address these two questions, the researcher will study:

5) Literature reviewIn this literature review, keywords were used to search studies and reports documented, including vaccine, vaccination, full vaccination, optimum vaccination, knowledge, attitude, hesitancy, refusal, cost, reminder, and caregiver. Similarly, the following key phrases were also used to search: subjective norm, caregiver experience, perceived behavioral control etc. all literature, including those terms, was searched and considered for review except for studies done before 2000. Evidence about adult vaccines and animal vaccines were excluded from the beginning and not considered for review. 5.1 Sociodemographic factors and optimum childhood vaccine uptakeSociodemographic factors are one of the factors that influence the personal decision to seek health services. M The study conducted in Italy showed that vaccine hesitancy is significantly associated with the economic status of caregivers ranging from OR of 1.34 to 1.59 from low to the severe low economic status of a mother. On the other hand, vaccine refusal was significantly associated with the education status of caregivers, with an OR of 1.89[1.23, 2.93].(19) Similarly, a study conducted in Bangladesh to assess factors that influence full childhood vaccination showed that children born from lower sociodemographic quantile have a lower chance of completing full dose childhood vaccination.(20) Another study conducted in Greece showed that children born from a minority group, those born outside Greece, born from a young mother and had many siblings or their parents were less educated found to be a chance of completing a recommended vaccine according to the vaccination schedule was very less likely. “The weighted proportions of children with complete and age-appropriate vaccination among households with three or more children were 26% and 38% lower, respectively, compared with those of households with only one child.” (21) Another study conducted in Nigeria proved that the sociodemographic status of a caregiver is one of the most influencing factors for optimal childhood vaccine coverage. The study showed that immunization coverage was significantly associated with childbirth order, place of delivery, number of children, maternal age, geographic location, maternal education, religion, literacy level, wealth index, and occupation at a 95% confidence interval in multivariate analysis.(22) The study, which was conducted to analyze factors influencing childhood vaccination coverage, showed that the sociodemographic status of caregivers took the highest share with 35%, followed by antenatal care utilization (17.7%), and maternal education (13.2%), and region.(23) Studies indicated that there is a huge variation in vaccination full coverage across regional states and even from region to Zone and woreda. The study conducted in the Waghimra Zone of the Amhara region showed the percentage of children who are fully vaccinated was higher than the national average but still lower than the World Health Organization (WHO) recommendation. In this study, the most significant sociodemographic factors that contributed to full vaccination coverage were maternal literacy rate, distance from a health facility, and place of delivery (home or health facility).(24) Generally, these studies conducted in the different countries showed that attaining a full course of vaccination according to the country’s immunization schedule remains unachieved, and it also gives a clear impression of how the sociodemographic status of caregiver influences full childhood vaccination. 5.2 Knowledge of caregivers and optimum childhood vaccine uptakeKnowledge is understanding of or information about a subject that you get by experience or study either known by one person or people generally.(25) In the context of this study, knowledge refers to the caregiver’s understanding of or information about vaccine and vaccination, vaccine-preventable disease, and the importance of vaccinating a child for his/her future life that was gained as a result of exposure to vaccine-related information either from a health professional, mass media and house to house volunteer campaign message or IEC materials designed for the purpose of promoting vaccination or informally from a family member, friends, religious leader or traditional leader. Studies showed that mothers’ knowledge about the importance of vaccination is highly correlated with the chance of children being fully vaccinated. A study conducted in Cyprus indicated that mothers with a good knowledge of vaccines were more likely to fully vaccinate their children, and this depended on who is the source of information; trust in the information and advice from a trusted person helped in increasing full vaccine coverage.(26) Improving a mother’s educational status has importance in improving the overall health condition of the family, including children’s vaccination. The study conducted in Nigeria to assess the association between mother knowledge and full vaccination coverage showed that the education status of mothers was highly associated with the chance of their children being fully vaccinated. More significantly, mothers who have an awareness of when to start immunization for their children are more likely to vaccinate their children until they complete the full course of the vaccine according to the immunization schedule of the country.(27)(28) Similarly, a study conducted in Eritrea showed that children born from educated mothers are more likely to be fully vaccinated compared with children born from less-educated mothers.(29) A study conducted in Amhara regional state hard-to-reach areas of Sekota Zuria woreda also showed that mothers’ knowledge of immunization was found to be highly associated with immunization coverage in general.(24) Overall, improving mother education has multiple significant not only on the health of the family but also on the overall development of the country. Hence countries are committed to improving female education enrolment at all levels. This commitment includes the Ethiopian government, which resulted in a significant improvement in female education. Female primary education enrolment improved from 9.4% in 1971 to 96% in 2015.(30) Similarly, through the deployment of Health Extension Workers(HEWs), each woman is getting basic health education, particularly on family health, including EPI, hygiene and sanitation and safe food handling, etc. this intervention basically helped to improve the overall basic health services and helped to improve health-seeking behaviour of the rural community.(31) However, the implementation varies from place to place and depends on the regional and zonal administrative commitment. 5.3 Caregiver’s intention to vaccination and optimum childhood vaccine uptakeThe way caregivers think and feel about vaccines and vaccination influences the decision to vaccinate her/his child. Definitely, a mother with a positive attitude towards vaccines and vaccination will have a high probability of vaccinating her child with full doses. The intention to vaccinate is one of the most decisive factors that affect a decision to vaccinate a child, and a mother needs to break this obstacle before her child gets full childhood vaccination. This will be influenced by individual attitudes towards a vaccine, perceived behavioral control, and the subjective norm. Perceived benefits of the vaccine also determine the chance of vaccinating a child with a full course of the vaccine according to the country’s immunization schedule. In addition, perceived behavioral control is one of the factors that interfere with the intention of the caregiver to vaccinate a child. For example, a mother’s decision to vaccinate her child will largely be determined by the influence of her husband; if a husband has accepted the decision to vaccinate the child, then it is highly likely the child will get vaccinated.(32) Such a kind of challenge to immunization programs is common in Somali, where a mother alone cannot make the decision to vaccinate her child even though the vaccinator went house to house in the absence of her husband. A vaccinator explained the problem in the following sentence: The main challenge we face is taking the vaccine to the house and discovering that the mother and/or child are away. If they are at home, another problem we face is being told that the father is away and that the mother cannot make the vaccination decision. This situation occurred this week during the measles campaign.(33) Similarly, the study conducted in Nigeria, Amibara state, showed that the perception of caregivers is significantly associated with full coverage of childhood vaccination, especially the perception of mothers on the vaccine efficacy, safety, and effectiveness found to be the most influential factors on caregiver decision to vaccinate children.(34) An increase in the knowledge of caregivers about vaccine improves both attitudes and practices on vaccination. Improving the knowledge of caregivers about vaccines cannot be achieved in the short term; these needs coordinated effort and sustainably improved access to information on vaccines and vaccination. Different countries use different strategies to increase caregivers’ knowledge and awareness about vaccines. The studies conducted in Nepal showed that the role of voluntary community health workers was very important in improving caregivers’ knowledge which in return resulted in high vaccination on childhood vaccination.(35) In addition to an awareness creation session targeted to improve the overall knowledge of caregivers on vaccine safety and effectiveness, the role of vaccine promotion using any available means, public opinion, and quality of vaccine service was found to be one of the determinants of attitude toward caregivers and this found to be linked with vaccination coverage.(36) Studies in different countries show that mothers’ positive attitude about vaccines and vaccination was found to be highly associated with the probability of vaccinating their children. A study conducted in the rural setting of western Uganda showed that mothers with better knowledge and awareness of vaccines were found to be more likely to vaccinate their children with full vaccine doses, whereas mothers with low awareness and poor knowledge of vaccines and vaccination were found to have a fear of the side effects and ignore to take their children to vaccination and less likely to vaccinate their children until they complete their vaccination.(37) Similarly, a study conducted in the Amhara region of Wadala woreda showed that a positive attitude about vaccines was significantly associated with vaccinating their children three, two-three times (OR=4.30) and four-five times (OR) 3.227). (38) 5.4 Accessing vaccination service opportunistic cost and optimum childhood vaccinationCosts associated with accessing immunization services are one of the obstacles that affect caregivers from taking their children to the vaccination site. In most cases, the cost includes the cost of administration of a vaccine, which varies from country to country and from public to private facility, and of course, the travel cost of the caregiver to reach the health facility from her/his home. These costs in the US range from around $8 to $29 for administering the vaccine, and assuming a caregiver will cover two hours for travel, it will cost around $23.(39) The cost of accessing the immunization service is not always directly related to the vaccine as the vaccine will be free in most area in the developing world; however, there is an opportunistic cost that affects the decision of caregivers to vaccinate children fully. Comparing children born from a poor family with children born from the richest family, those born from low economic families are 36% less likely to be fully vaccinated at childhood age.(40) There is no proven evidence in the developing country how the cost of traveling hours on foot to get a vaccine will be calculated in terms of money. This remains difficult to calculate, and the feeling will vary from place to place and person to person. In the area where this study will be conducted, the cost of administering a vaccine will be covered by the government, and no cost will be paid by the caregiver. Similarly, transportation costs cannot be calculated easily as a caregiver will walk on foot for hours to reach health facilities. 5.5 Caregiver health facility experience and optimum childhood vaccinationHealth facility experience matters a lot for a caregiver to make another round of visits to get vaccination services. Health facility experience includes caregiver satisfaction with the service provided, health professional communication skills, and missed opportunities. Caregiver satisfaction determines her return visit to the same health facilities; caregivers who are not satisfied with the service will have a low chance of returning for a similar service. A study conducted in Nigeria showed that only 19.4% of mothers who participated in the study were satisfied, while a significant majority (80.3%) were undecided, and 2% of the mothers were dissatisfied with the immunization service provided.(41) A study conducted in Egypt showed that 95% of mothers were satisfied with the immunization service provided at the health center level; however, the satisfaction rate was not associated with full childhood vaccination coverage.(42) Similarly, studies conducted in Ethiopia on the satisfaction of mothers on immunization services showed that a significant number of mothers are not satisfied; only 68.2% of mothers included in the study reported that they were satisfied; however, this study did not mention anything about the association of low vaccination coverage and mother satisfaction with the service.(43) Caregivers’ satisfaction can be affected by different factors, including the health workers’ communication skills. Nowadays, as technology advances, health professionals’ ability to improve communication skills to interact with patients and family members is not improving; health professionals are failing to understand the patient’s biological and psychological problems and empathy to feel their problems and explain how they will be helped. This has a lot of consequences, including a lack of adherence to treatments.(44) Similarly, health professionals understand the challenges of caregivers in obtaining immunization services need to be understood, and they should be helped in a way they will continue to visit the same health facilities. Health professionals’ attitudes towards treating their clients, their technical competency, and their communication skills have a very significant impact on treatment effectiveness, on the client’s knowledge and satisfaction. Similarly, in immunization, health works qualities can be reflected in terms of the coverage and dropout rates, and it will have large consequences at large on the herd immunity (community will be vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases).(45) Studies showed that caregivers who met health professionals with good interpersonal communication skills are more satisfied though this area still needs further study; very few health professionals were found trained in interpersonal communication skills in an area where studies were conducted. (46) A missed opportunity is another challenge caregivers face at a health facility who are visiting for immunization service. A missed opportunity refers to an act of caregivers or any eligible person who is eligible for vaccination contacted with health service points and unable to get vaccinated with the intended vaccine type due to several reasons.(47) The missed opportunity is one of the challenges that affect immunization coverage in many counties. Reason for missed opportunities includes the failure of health facilities to administer all vaccines at the same time for eligible children according to the country’s immunization schedule, false contraindication, health professionals’ practice of being unable to open multi-dose vaccine vial for a small number of children to avoid vaccine wastage and logistics problem.(48) The knowledge of health workers to identify contraindication is one of the factors that increases the magnitude of missed opportunities. Studies showed that the knowledge of health workers on contraindication was found to be insufficient or failed to identify it; a study conducted in Burkinafaso showed that 83% of health workers were not able to identify the correct contraindication from the vaccine.(49) Reducing missed opportunities alone will significantly improve vaccination coverage in general and will contribute to getting children fully vaccinated around the globe. Studies showed that reducing missed opportunities alone can improve vaccination coverage in a country by up to 30%.(50) 5.6 Caregivers after service experience and full vaccination coverageCaregivers after service experience like the absence of reminders, health workers unable to explain the common side effect the child may have, cue for action, talking next steps (which of the vaccine the child already received and which vaccine left according to the national EPI schedule), health professional unable to receive caregivers’ feedback about her experience at the point of service etc. will significantly affect the chance of caregiver to do her next visit in the same facility. Evidence showed the more caregivers received balanced information on the benefits of the vaccine and side effects, the more they will be confident to decide on vaccinating their children with a specific vaccine. However, practice from the field showed low to moderate confidence in the vaccine as the amount of information they have remained either limited or not balanced.(51) One of the reasons for missing the schedule for immunization is the educational status of the caregiver and unable to put a reminder about the schedule of the next vaccination. The evidence from Nigeria showed that nearly 90% of caregivers agree that mobile text messages will help to remind vaccination schedule, and they were willing to receive a text message, and about 91% of the respondent said that it would be helpful for them.(27) One means of reminder is to send a mobile text to caregivers regarding the next vaccination schedule, and this was found very important for middle and low-income countries; keeping in mind the timing and repetition of the message affects the decision of the caregiver on taking the child to vaccination site for next schedule.(52) Fear of vaccination side effects is one of the top reasons for caregivers not to vaccinate a child. In addition, inadequate information on the timing, place of vaccination, and the type of vaccine being given has an effect on vaccination coverage.(53) Due to the low staffing in the health sector, it is less likely that health professionals will explain to caregivers about the side effects and next steps during the time of vaccination. This study will carefully observe the practice of frontline health workers on vaccination and their interaction with caregivers. In addition, the previous experience of caregivers will be assessed house to house through structured and unstructured questionnaires to determine how their interaction affected their decision to vaccinate their children fully. 6. Methodology6.1 Study areaThe study area where this study was conducted was located was 254 km northern Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The area is highly marginalized due to a lack of access to an asphalted road that can link to the capital city, and hence supplies that come from other areas are very expensive and not affordable to the local residents. The gravel road that links the area to Addis Ababa is not accessible for small cars all the time, and during summer, it will also be very hard to access the area for long trucks too. The area that can be covered by this study is commonly called the Menz area, which covers about five woredas, namely Menz Lalo, Menz Mama, Menze Gera, Menz Keya, and Menz Gishe. The total population of these five woredas was estimated at around 600,000 though there is no population census conducted to know how many populations exist currently. As far as the researcher’s knowledge is concerned about the study area, though there was an effort to solve the health problem using HEWs, there are still unresolved challenges the community is facing. 6.2 Research approachThis study used both qualitative and quantitative research approaches (Mixed approach). The mixed research approach is used for inquiring information based on the assumption that collecting the diverse type of data provides a complete understanding of a research problem than either quantitative or qualitative data alone. The study began with assessing quantitative information of caregivers that were collected from the sample study participants, which was used to generalize the population; on the other hand, a qualitative study was used to collect detailed information from the study participants to explain the result obtained through the quantitative study. In this study, both qualitative and quantitative data were collected at the same time. The result was analyzed in a similar period separately. The finding was interpreted in the discussion section to compare the finding from the quantitative with the qualitative result.(54) 6.3 Study designResearch design is the conceptual structure within which this research will be conducted; it constitutes the blueprint for the collection, measurement, and analysis of data. This study used a convergent parallel mixed study design to determine factors influencing optimum childhood vaccine uptake in the North Shoa Zone of Ethiopia, particularly in Menz woredas. 6.4 Study populationThe study population was caregivers who are living in five Woredas of the North Shoa zone in Ethiopia. The sample was selected from the study population; caregivers who have children aged between 12-3months of age. 6.5 VariablesA variable in research means simply a person, place, thing, or phenomenon that we are trying to measure in some way.(55) Basically, variables are those factors that affect (facilitate or impede optimum childhood vaccination), which will be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively. These variables include caregivers’ age, educational status, sociodemographic status, knowledge, and awareness about the vaccine, attitude, norm, perceived behavioral control, cost (direct and indirect cost), and caregivers’ pre-and-post health facility experience (during and after immunization service) and vaccine promotion related information. 6.6 SamplingThe sampling technique will follow multi-stage cluster sampling to determine the ultimate sampling units. In this case, this study had considered woredas as a primary sampling unit. The second stage sampling unit was Kebeles of caregivers who were included in the study. The third stage sampling unit, the ultimate sampling unit, is households where caregivers live in. 6.7 Sample size determinationA single proportion formula will be used to determine the quantitative sample of caregivers to be included in the study. Whereas the qualitative sample was taken from the same sample but lower number of caregivers for obtaining more detailed information on similar variables under consideration in this study. Considering the 2018 EDHS result, which shows the national full immunization coverage was 38.5%, the sample calculated was 364 with a margin error of 5% and at a 95% confidence interval. Considering 10% non-response rate, the sample was adjusted to 400. Hence, 400 caregivers were proportionally selected from the total kebeles that were included in the study. Of these study participants selected for the quantitative survey, 20 caregivers were selected for an In-depth Interview (IDI). Detailed information was collected from urban, semi-urban, rural, and remote settings of the study area. 6.8 Data collectionBoth qualitative and quantitative data were collected from January to February 2022. Data collectors were trained for both qualitative and quantitative data collection on the developed tool theoretically and practically before they went to the field to collect actual data. The practical training session was conducted for data collectors on how to use the KoboCollect application besides the questionnaire, and demo data was entered to assess their familiarity with the application. 6.9 Method of data collectionQualitative data was collected using close-ended questionnaires through a trained data collector. On the other hand, qualitative information was collected in open-ended questionnaires prepared to assess factors affecting optimum childhood vaccination according to the caregiver’s journey to immunization, it recommend to use in combination with other data collection. (57) Quantitative data was collected through a house-to-house interview using pre-designed structured questionnaires that were deployed on the KoboCollect mobile-based application, and data was collected using smartphones. At the same time, the qualitative data will use unstructured questionnaires and use both in-depth interviews and observational techniques to collect an in-depth understanding of the situation. In-depth interview: it is a qualitative data collection technique in which one-on-one engagement of participants will take place to explore detailed information about a certain issue. This can be conducted either in person or through a phone interview; the former is a more favorable technique as it will give a better experience of collecting detailed information.(58) The in-depth interview was conducted among selected caregivers using structured interview questionnaires prepared in advance. 6.10 Data processing and analysisBoth qualitative and quantitative data were collected at the same time, and quantitative data was exported from Kobo Collect to MS Excel and then to SPSS version 28. After the data was exported to SPSS, the necessary data cleaning activity was conducted by the researcher. Once data cleaning was completed, the analysis was done starting from basic descriptive statistics and binary logistic regression to determine the degree of association of each variable with the dependent variable. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was done to check which factors have a real association with childhood full vaccination status. On the other hand, qualitative data were collected using open-ended questions, and transcription was ready in Microsoft word document, which later changed to classify according to the theme using Microsoft excel. Each response was coded according to themes, and results were generated for each variable. 6.11 Validity and reliabilityValidity refers to the degree to which the survey measures the right elements that the researcher wants to measure. In a simple term, it means how well the questionnaire can collect the intended response.(60) The data collection tool was checked for validity at different stages. The first stage was to test face validity by asking experts in the area of immunization to rate the questions whether these tools were suitable to collect the intended response or not using the Likert scale (5 to highly suitable to collect the intended response and 1 for inadequate to collect the intended to collect the correct response). The question that got a score of 6 and below from five responses was not considered for collecting data. The reliability of a research tool is the other important factor that the researcher will consider. Reliability refers to the consistency of results; it means the questionnaire will produce the same result being conducted repeatedly under the same condition.(61) Hence, this research work has ensured the reliability of the questionnaire by testing and re-testing questionnaires at different times but same respondents. Testing and re-testing of the questionnaires were conducted in a similar community but which was out of the target population for the final study. 6.12 Ethical considerationEthical consideration is a set of rules and regulation a research activity needs to follow when implementing any study. Ethical consideration guides the research design and practices. The goal of ethical consideration in research is to understand real-life phenomena, study effective treatments, investigate behavior, and improve lives in other ways. Basically, ethical consideration is intended to: Protect the rights of research participants, enhance research validity and maintain scientific integrity. (62) This research activity was conducted maintaining ethical issues as its highest concern area so that the rights of caregivers who participated in this study were protected from any kind of harm or right violation because of their participation in this study. This study has been following all scientific study procedures, including step-by-step Institutional Review Board (IRB) approvals. Before commencing the research interview process, each participant was asked for their consent to participate, and the researcher had explained their full right to participate or not and to withdraw at any time of the process. Each study participant was asked their consent to continue in the interview process. Study participants who complained about the length of the interview and who were not interested finish the process were given the right to do so. During the process of obtaining permission to conduct this study, the Amhara region North Shoa zonal health office and woreda health bureau were communicated about the study’s purpose, and they asked to share the finding by the end of this research process. 6.13 Limitations and delimitation of the studyLimitation: this study is a cross-sectional study where the information was collected at a spot where the data collector contacted caregivers during a house-to-house data collection. This study assumes that caregivers will have a good memory of their health facility experience and able to recall what was their challenges when they travel to health facilities. However, recalling information may depend from person to person and may affect the quality of information obtained. The researcher recommends that future studies focus on an observational study to understand the interaction of caregivers with health facilities and document each process as things happen. This study also used the category of vaccination status, i.e., fully vaccinated and incomplete. However, there is a range of differences even within the categories, like children who received only one dose through outreach vaccination campaigns and children who missed one dose from basic vaccines, which will affect the generalization. Delimitation: this study will focus on factors influencing childhood vaccination only from caregivers’ perspectives in the selected woredas. Due to time and cost, the researcher was not able to include the perspective of others which will remain an area of study for interested researchers in the field. 6.14 Pilot studyA pilot study in research is very important not only to make sure the tools that are going to be used can work to collect the intended information but also to understand whether the overall research approach can work well and the planned budget and time also the right fit for continuing the activity. Research activity is very important, particularly for clinical research. Conducting a pilot study will help the researcher to save time money and increase effectiveness while conducting the large-scale study or the main research activity in the field.(63) A pilot study was conducted in 5% of the study sample in a similar population but not the same study area. 6.15 Result dissemination planThe study result will be communicated to Amhara regional health bureau, zonal health office, and woreda health offices, respectively, to inform the finding and the recommendations the researcher will make by the end of the study. In order to make this practical, the researcher will organize a one-day workshop in coordination with any partner that can support this study, and the finding will be presented to participants. 7. Theoretical FrameworkCompletion of childhood immunization can be influenced by both internal and external factors. This study assessed factors related to caregivers or parents that affect their decision to vaccinate their children. These factors affect the decision-making ability of caregivers and are found at different stages. They are mainly presented in six thematic areas according to the caregiver’s journey to the immunization framework. This study will utilize the caregiver journey to vaccination framework to explore factors influencing the decision-making of caregivers at different stages, both qualitatively and quantitatively. 7.1 Theory of planned behaviorThe theory of planned behavior assumes that individuals act rationally on a certain behavior according to their attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control. It argues that these factors may not necessarily or consciously be considered during decision-making but from the backdrop of the decision-making process. According to this theory, the three factors, either in combination or one of the factors alone, may lead to intention, and the intention will lead to behavior, or each factor alone or in combination may lead directly to behavior change.(64)

Figure 1 Theory of Planned Behavior 7.2 Socioecological modelThe socioecological model broadly sees health as multiple effects of several factors related to individual, family, community, and societal levels. Individual health can be affected by the interaction of a family, community, and society at large. Similarly, caregivers’ decision to vaccinate children will be influenced by different factors starting from individual-level perception to family influence and community-level awareness about the vaccine as well as the overall policy of the government. Hence, the caregiver journey to immunization framework considered utilizing concepts from the socioecological model to understand multiple level factors that influence childhood optimum vaccination status. (65)

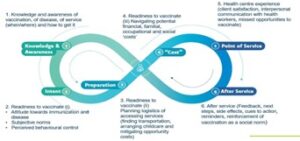

Figure 2: The socio-ecological model 7.3 The caregiver’s journey to the immunization frameworkThe caregiver’s journey to vaccination covers six factors that are related to knowledge and awareness of caregivers towards vaccination and vaccine-preventable disease, her/his intent, ability to decide to take children to the vaccination site and vaccinate the child, household ability to afford to travel to vaccination site, costs associated with taking the child to vaccination site (cost-benefit), caregiver experience at the vaccination site and post-vaccination experience of caregiver and vaccine consequences. These factors are interlinked and explained in the caregiver’s journey to vaccination. The health belief model was a predominant traditional model that explains how certain behavior is practiced and what are the triggering and inhibiting factors. This model was mainly based on the individual past assessment of intention, attitude, and behavior. Considering this limitation, UNICE and other partners developed the caregivers’ journey to immunization framework as a novel way to contextualize and understand caregivers seeking childhood immunization services.(57) This study will explore both qualitatively and quantitively how these factors influence optimal childhood immunization. Experts’ suggestions showed that understanding and improving the caregiver’s journey to immunization would contribute to positive immunization outcomes such as the completion of recommended vaccination schedules, on-time completion of childhood vaccines, and reduced vaccination dropouts.(57) Figure 3: The Caregiver Journey to Vaccination 8. Result8.1 SociodemographicA total of 404 participants were included in the study, and 371 were willing to stay until the end of the interview session and provide full responses. Out of participants who were willing to give their responses, 298 (80.3%) were female, mainly the mother of the child, 261 (70.4%), and 59(15.9%) of them were the father of the child. The rest of the study participants were grandfathers and grandmothers of the last-born child. Participants included in the study from remote, rural, semi-urban and urban areas. Regarding the educational status of the participants, as shown in the pie chart above, the highest number of 138(37.2%) of the participants were elementary completed, followed by high school complete 111(29.9%) and 90 (24.3%) them were those caregivers who do not have any formal education. The rest segments of the study participants were those who had a higher educational status of degree and diploma 13(3.5%) and 19(5.1%) of the total participants, respectively, and they were living in urban settings. Regarding the occupational status of the study participants, about 244(66%) of them were farmers, followed by merchants who were 44(12%). The rest of them were employees, 34(9%), and other combinations of different businesses were about 41(11%). Significantly, a higher proportion of study participants, 340 (91.6%) of participants’ household annual income fall below 500000 ETB, which is approximately less than $1000 per household. Regarding the religion and ethnic composition of the study participants, all of the participants were Orthodox Christian, and 370 (99.9%) of them were ethnic Amhara. The average distance of health facilities that provide vaccination services was 6.09 km, where the minimum distance was 0.4 km, and the maximum distance was 18km in remote parts of the study areas. Regarding the vaccination status of the last-born child, about 218(59%) of them were fully vaccinated. Table 1: Vaccination status by areas of residence

The vaccination status of children was also found to be affected by caregivers’ educational status. As shown in the table below, children born to caregivers with a diploma and above educational status were found to be more likely to get fully vaccinated as compared with children born from caregivers who do not attend formal education. Table 2: Full Vaccination Status and Caregivers Education

8.2 Association of sociodemographic variables and full vaccination statusVariables like the educational status of the caregivers, area of residency, and distance from the health facility were found to be significantly associated with the full vaccination status of children. Caregivers who did not attend school were found to be 77.1% less likely to fully vaccinate their children compared with their educated counterparts, with a P-value of 0.03. Similarly, children born in rural, remote, rural, and semi-urban areas of the study area were found to have a significant negative relationship with full vaccination status. As shown below in the table, children born in rural and remote areas found to be 77.1% and 76.3% less likely to get fully vaccinated with P-values of less than 0.001. Similarly, children born in semi-urban areas have less chance of being fully vaccinated as compared with children born in urban settings. Generally the sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers affects the vaccination status. Table 3: Association of sociodemographic variables with full vaccination

8.3 Vaccine PromotionVaccine promotion is a way information is communicated in the community, including the source of information, the credibility of the information, and adequacy of the information to the extent it can help the community members be convinced to vaccinate their children. 8.3.1 Source of informationThis study indicated that the main source of information about vaccines is health professionals/ Health Extension Workers (HEWs). From a total of responses, 280 (72.4%) of them get information through HEWs house to house information dissemination, followed by kebele leader 92(23.8%). Other sources of information like TV/radio, friends, and social media seems among the least utilized source of information. Similarly, HEWs were the most trusted source of information about vaccines in the community, followed by Kebele leaders. 8.3.2 Caregivers’ opinions about vaccine promotionOut of the total study participants, 267(72.3%) of them agreed that the way vaccines had been promoted in their communities was enough to motivate caregivers to vaccinate their children. In the meantime, a significant number of them believe that the vaccine promotion in their community was not adequate for informing caregivers about vaccinating their children. https://irpj.euclid.int/wp-admin/upload.php https://irpj.euclid.int/wp-admin/upload.php Table 4: Caregivers’ opinions about vaccine promotion in their communities

8.3.3 Qualitative data result [in-depth interview] about vaccine promotionThe qualitative study showed that most of the vaccine promotion, including the time of vaccination (vaccination schedule) mainly done through health professionals (HEWs) and Keble leaders. Most of the caregivers agree on the adequacy of vaccine promotion done in their community, while few of them reported that they did not get adequate information about the vaccines. A caregiver from Yigem Kola Keble 05 respondent’s ID 003 stated her experience regarding vaccines promotion in her community. Well, there is vaccine promotion. Most of the time, health professionals do it. Sometimes, the kebele leader will call on the phone and tell on the presence of vaccination and the date of vaccination. We got additional information from health professionals on the benefits of vaccines during our visit to the health facility. They told us the type of disease vaccine could prevent and the need for continuing routine immunization monthly. 8.3.4 Association of vaccine promotion and full childhood vaccination statusThere was no significant association found between the full vaccination status of children and vaccine source of information and the opinion of caregivers about the adequacy of vaccine promotion. However, the qualitative information showed that vaccine promotion had contributed a lot to starting vaccines on time. 8.4 Knowledge and awareness about vaccineOut of a total of 371 respondents, about 338 (91.1%) of them thought that childhood vaccination could help to prevent disease. Caregivers were asked to mention the type of diseases that vaccines can help to prevent, and a significant majority, 234 (63.07%), of them mentioned measles, followed by tetanus, 135 (36.39%), and polio, 39 (10.51%). Other different diseases like diarrhoea, night blindness, headache, common cold etc., sum up to give the rest majority. At the same time, other important diseases like TB, HPV, Hep, and pneumonia were found to be the least known by the caregivers. In an area where this study was conducted, a significant majority of them, 265(71.4%), give birth at home and miss the first vaccination like polio 0. In addition, they did not know when to start vaccination and complete it. A majority of caregivers, 242(65.2%), did not know when to start vaccination for their children and when they could complete it. The vaccination status of children was determined through vaccination card observation by data collectors and through an interview of caregivers regarding their status in cases where vaccination cards are misplaced. During the data collection period, only 217 (58.5%) of the caregivers have the vaccination card. Out of the total study participants, 239(64.4%) of them had an awareness of vaccine side effects. The most commonly mentioned side effects were fever 181(50.7%), swelling 126 (35.29%), and local pain 70(19.61%). The majority of them, 225(63.03%), had an awareness of what action was needed in cases of vaccine side effects. Though a significant majority of the total respondents, 89.08% of them, know where they can get childhood vaccination, still there are a few respondents who do not know where they can get vaccines. Most of these respondents were those who live in remote and rural parts of the study area. About 349(94%) of caregivers who participated in this study agree that vaccination is important for the health of children. Similarly, 346 (93.26%) of the total respondents agree that all children should get fully vaccinated to be protected from diseases. 8.4.1 Qualitative data results (In-depth interview) about the Knowledge and Awareness of VaccinesQualitative data was collected from two towns, semi-urban areas, and rural and remote kebeles of the study area. In-depth interviews on the knowledge of the caregivers about full childhood vaccination are summarized in the following way. Table 5: Description of caregivers’ response on on vaccine knowledge

8.4.2 Benefits of vaccinesMost of the caregivers know the benefits of vaccines; regardless of the expression, they say vaccines are important for the better future of children. They think childhood vaccination helps children grow healthy and strong. They understood the benefits of childhood vaccines for the family as well. The majority of them said childhood vaccines help family members by avoiding unnecessary stresses when children get sick. A respondent from Molale town with an interview ID of 015 stated the benefits of the vaccine in the following way: Well, vaccines are very important in many ways; children who get the vaccine will be healthy. Vaccines prevent different diseases like measles, smallpox, tetanus, and other diseases… even they can prevent disabilities. It also helps to make the bone strong. Overall, the vaccine helps children to grow healthy and strong. I usually hear about vaccines’ benefits from health workers and radio. Another respondent from rural kebele of Menz mama Emegua kebele with a respondent ID of 011 stated the benefits of vaccines as follows: “vaccines are key to prevent disease outbreak (ተስቦ-Teasibo) and anyone vaccinated can be prevented from the disease easily.” On the other hand, there are caregivers who do not have a good understanding of the benefits of vaccines. They think vaccines are not as relevant to the health of the child and think sometimes vaccines may cause serious complications. There are caregivers who gave a response during this study who said vaccines themselves might kill the child. Respondents with an interview ID of 05 from Kewariat Keble stated their understanding of vaccines in the following way. I think it will not be bad for children if they are not vaccinated. I do not think unvaccinated children will develop the disease. Instead, vaccinated children will develop the disease. They will develop diseases when they had injected with the vaccines. This cause problem for the family and the child. I prefer not to vaccinate my child. Most of caregivers share similar ideas on the type of disease childhood vaccines can prevent. They said childhood vaccines could prevent diseases like measles, polio, and flu. If vaccinated, children will be protected from these kinds of diseases. This research showed that there were also misperceptions of vaccines’ benefits, like children playing on dirty playing fields can be protected from being sick because they are vaccinated. Caregivers were also asked about the benefits of fully vaccinating children. Most caregivers believe that fully vaccinating will help children to get full protection from diseases. They believe that partial vaccination is partial protection. A respondent ID 002 from Kolo Margefia stated that “well, the benefits of fully vaccinating children is to help them being protected from many diseases. One vaccine cannot prevent all types of diseases. If the child is fully vaccinated, then he will be protected from many diseases.” 8.4.3 Consequences of unvaccinated childrenMost of caregivers believe that unvaccinated children will face problems. They also expressed the burden on families, including financial and psychological burdens as a result of children’s sickness that could be prevented by vaccination. The response from a caregiver with a participant ID 017 stated as follows: The unvaccinated children will face many problems; they may develop a disease like measles, polio and flues, and tetanus. Children who suffer from disease will not grow healthy. There is also a consequence on the family. When children get sick, we will be stressed, and this is not good for the whole family. The other caregiver from Molale town 01 Keble with a respondent ID 12 indicated that an unvaccinated child would cause a burden for the entire family. The caregiver believes that an unvaccinated child may be a reason for disease transmission in the community. She said, “the unvaccinated child will cause disease for other children in the family. The child who is not vaccinated will develop disease first, and it can transmit to other healthy children.” On the other hand, caregivers who were not aware of vaccines’ benefits believe that there is no consequence of being unvaccinated. They believe vaccines themselves will cause a burden to children due to their unpleasant effects after vaccination like fever, pain at the point of vaccination, and sometimes more complications, according to their thought. 8.4.4 Association of caregivers’ knowledge and awareness and full vaccination statusThe caregivers’ knowledge about when to start the vaccination, complete it, and their awareness about the place where vaccination will be given was found to be significantly associated with the full vaccination status of children. Caregivers who know when to start vaccination and when to complete it were found 9.22[5.15, 16.49] times highly likely to fully vaccinate their children during childhood with a P-value of less than 0.001 at 95% CI. Likewise, caregivers who know where to get vaccines were found to be 7.72[2.72, 12.02] times more likely to fully vaccinate children with childhood vaccines. 8.5 Decision making and process of getting the vaccinationThere are different steps caregivers need to pass through to get their children vaccinated. This begins with a motivation to decide on vaccinating a child, and that usually comes from a close family member. For most of the caregivers, encouragement comes primarily from their spouse 204(54.9%), followed by other family members 147(39.5%), 112(30.25%) HEWs, and kebele leaders 37(10%), respectively. The majority of decision-makers on vaccinating a child were found to be caregivers themselves. Generally, the overall attitude of the communities about the vaccine was found to be encouraging. About 345 (92.99%) caregivers responded that the community attitude about vaccination is encouraging. Friends were found to be one of the highest proportions in terms of discouraging vaccination, followed by mothers and other community members. Once the caregiver decides to vaccinate, the next challenge is arranging transportation to the vaccination site. Regardless of the distance between the health facility and the house of caregivers, most of them, 345(93%), travel on foot to get vaccination services. About 37(10%) of the total respondents need to travel on foot more than 8km, with a maximum of 18km, to get their children vaccinated. Once after, the caregivers manage to arrive at health facilities where vaccination services will be provided; their chance of getting their children vaccinated will be determined by other factors like the availability of vaccines and getting the health facility open. About 255(68.7%) of them can get the vaccine without any difficulties in health facilities any time they visit. At the same time, a significant number of caregivers have a challenge accessing vaccines when they attempt to vaccinate their children, including health facilities permanently closed in their areas. Table 6: Experience of caregivers to access vaccines when they visit health facilities

Another challenge for caregivers to get vaccinated their children were the presence of competing priority. Caregivers should make sure children and other family members, as well as the entire household, need to be handled carefully in their absence. Hence, especially mothers need to assign someone who can take care of the rest of the children and the household before heading to a health facility. In the means time, it is not an easy task to get someone to assign who can handle this responsibility. More than 234 (63%) of the study participants indicated that it was not easy to assign someone when they went away for vaccination. Table 7: Caregivers’ experience of getting someone who can take care of their house when they travel to the health facility.

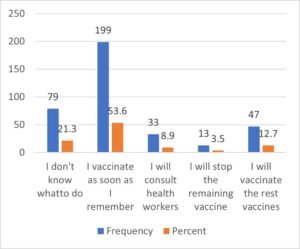

Usually, caregivers will be scheduled on a certain day to visit the health facility; however, that day may not be convenient for them to visit health facilities. For example, they may face a problem that requires social responsibilities like attending funeral ceremonies, where caregivers should attend or must delegate someone. caregivers were asked to mention some of the obstacles that prevent them from visiting health facilities and consequently lead to being unable to vaccinate their children fully. Even though the majority, 251(67.65%) of them, indicated that there is no such problem with visiting health facilitie, at the same time important portion of caregivers still faces many challenges in vaccinating their children. In this study, caregivers reported that forgetting the vaccination schedule was not a common problem. About 320(86.3%) of them reported that they could not forget their vaccination appointment. For the question, caregivers asked what they would do if they forgot their schedule; nearly half of them, 199(53.6%), responded that they would immediately take their children to the health facility. In the meantime, a significant proportion of caregivers, 79(21.3%), did not know what to do.  https://irpj.euclid.int/wp-admin/upload.php Figure 4 : Caregivers’ response on actions they will take if they forget their vaccination schedule As caregivers will have so many responsibilities, and while they focus on their household activities, chances are high to forget their vaccination schedule. There are different means to remember vaccination schedules, about 169(45.6%) of caregivers use their personal reminders, while 127(34.2%) of them were helped by HEWs to remember their vaccination schedule. About 32(8.6%) of them did nothing to remind the vaccination schedule. 8.5.1 Qualitative data finding [In-depth interview] on the decision-making and process of vaccinationQualitative data on the decision-making and process of vaccination findings showed that there are different actors involved in decision-making and challenges that encounter the process of vaccination.

Table 8: Description of caregivers’ response on vaccination decision making process