ABSTRACT

| This study examines climate variability and change, focusing on the Sahel region, notably Burkina Faso. The region faces an increase in extreme weather events, whose multidimensional impacts affect the biophysical environment and the stability of local socioeconomic systems. These challenges underscore the urgent need to strengthen adaptation and mitigation strategies in response to these phenomena. The methodology combines quantitative and qualitative approaches, collecting data from approximately 200 people per study area through questionnaires and interview guides. The main results reveal a growing awareness among populations of the effects of climate change on their natural resources and livelihoods. This awareness is accompanied by major concerns about the sustainability of their way of life, which is often threatened by these phenomena. In response to these challenges, innovative and resilient community strategies have been implemented to mitigate these impacts. The analysis also highlights that sociodemographic factors such as gender and age play a decisive role in awareness, education, and the implementation of appropriate ecological practices. At the policy level, it is essential to deploy integrated policies, raise awareness, and strengthen local capacities to reduce the impact of climate change and promote the resilience of vulnerable communities. These findings provide a concrete framework for guiding public interventions and promoting sustainable resource management in the Sahel by strengthening the capacity of populations to cope with future climate challenges.

|

|

- Introduction

Climate change is now recognized as one of the significant global challenges, impacting the environment and the social system at different scales. Following the findings of the IPCC, its effects are manifested globally by rising sea levels, increased frequency of extreme events, and loss of biodiversity, while inducing local changes in ecosystems, agricultural activities, and lifestyles(1). These adverse effects directly affect vulnerable communities’ livelihoods, food security, and socioeconomic stability. The interconnectedness of all these challenges underscores the importance of studying how local populations perceive and respond to these transformations to guide adaptation and resilience strategies effectively.

The increased frequency of extreme weather events, such as droughts or floods, exacerbates these challenges by directly affecting natural resources, agricultural production, and causing migratory movements, particularly in the Sahel, where water scarcity and land degradation intensify vulnerability and local conflicts.

In Burkina Faso, growing awareness of climate issues has led authorities to adopt measures such as reforestation, promoting renewable energy, and sustainable agricultural practices. These actions are part of a desire to reduce environmental impact while ensuring integrated socioeconomic development. However, the heterogeneity of these actions is closely linked to local perception and understanding of risks, which are influenced by socio-cultural, economic, and institutional factors(6).

With weak adaptive capacities and a lack of information, risk perception often limits concrete action. Therefore, developing a detailed understanding of these perception and action mechanisms is crucial to designing participatory policies, integrating local knowledge, and promoting sustainable governance. Managing the complex interactions between perception, resource management, economic activities, and migration remains essential for developing resilient strategies to face this multidimensional, local, and global crisis.

This doctoral thesis aims to analyze the repercussions of climate change on these various systems, by producing scientific knowledge that can feed into the development of tools for both decision-making and alert management, and whose operationalization could contribute to anticipating and limiting the harmful effects of climate change on local populations.

Therefore, this research aims to study the complex relationship between climate change and natural and economic systems and their practical implications for vulnerable populations to propose adapted and sustainable strategies. The specific objectives of this research include:

- Explore how local populations perceive and interpret the effects of climate change on their immediate environment.

- Analyze the concrete strategies adopted by these populations to cope with the impacts of climate change. These strategies include the diversification of economic activities, the adoption of resilient agricultural practices, and the development of community-based natural resource management systems.

- Explore the complex dynamics between impact perception, natural resource management, the local economy, and migration flows. These interdependent elements shape the resilience or vulnerability of populations.

This article will be structured into some parts to address the research objectives. The first section will be devoted to a literature review on climate change, its impacts at the global and local levels, and issues related to public perception and adaptation strategies. It will establish the conceptual and theoretical framework. The second part will present the methodology used, including a description of the study area, data collection techniques (surveys, interviews, observations), and the analytical approaches adopted.

The third part will analyze the results, including local perceptions of the effects of climate change, adaptation strategies mobilized by communities, and the interdependent dynamics between perception, resource management, and migration. The final section addresses the practical implications of these results for the design of decision-making tools. It proposes recommendations for strengthening the resilience of populations vulnerable to climate change, discusses the progress for each durable solution, draws conclusions, and makes recommendations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptual review

This conceptual review analyses the relationships between several key concepts related to climate change: local knowledge, adaptation, biodiversity management, and economic systems. Understanding these interactions is essential for developing integrated strategies that promote community resilience and sustainable development, especially in contexts vulnerable to climate change.

The review first defines each concept: climate change refers to a sustained variation in climatic conditions, influenced by natural processes or human activities; the local knowledge brings together indigenous knowledge specific to each environment; adaptation involves adjusting human and natural systems to reduce negative impacts or exploit new opportunities; biodiversity management aims to conserve and sustainably use biological diversity to maintain ecosystem functions.

The interconnections between these concepts are also analyzed. Local knowledge is fundamental to developing effective adaptation strategies, such as using traditional agricultural or water management techniques. Sustainable biodiversity management often draws on this knowledge to preserve ecosystem health while supporting local livelihoods, for example, by integrating native species into agroforestry.

Furthermore, adaptive capacity also depends on local economic systems, which, by adopting sustainable practices, strengthen food security and resilience. In response to environmental stresses, migration also influences these dynamics, supporting resilience through remittances or altering social and economic interactions. Finally, the socio-ecological systems framework highlights the interdependence between these elements, emphasizing the importance of holistic management integrating local knowledge to ensure sustainability.

2.2. Empirical review

This empirical review presents several integrated approaches for sustainable natural resource management and rural development in the face of climate change challenges. The ecosystem approach, adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity, aims to preserve the health of ecosystems by integrating their ecological, social, and economic dimensions. The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA), developed by DFID, emphasizes the balanced use of five types of capital (natural, human, social, physical, and financial) to strengthen household resilience to environmental and economic shocks. For example, rural communities can better cope with drought or food crises by combining agricultural diversification with capacity building.

Neo-Malthusian theories emphasize that population growth and excessive resource consumption exceed the planet’s limits, requiring more rigorous population management and sustainable lifestyles. In contrast, the migration approach sees migration as a proactive adaptation strategy that allows populations to diversify their sources of income and strengthen their resilience to environmental impacts. Market systems development and territorial market theory emphasize the importance of strengthening short supply chains, local participation, and adapting agricultural policies to ensure food security and sustainability. These different, complementary approaches offer an integrated framework for resilient territorial management in the face of climate challenges, particularly in the Burkinabe context.

2.3. Theoretical review

This theoretical review synthesizes existing research on the interaction between local knowledge, climate change adaptation, sustainable biodiversity management, and African economic systems, particularly forest-related livelihoods, food markets, and migration-environment-climate dynamics. It highlights the usefulness of traditional knowledge in strengthening community resilience to climate hazards, particularly through adapted agricultural practices, community water management, and ecosystem conservation. Studies in Burkina Faso and elsewhere show that integrating this knowledge promotes better management of drought and flood risks, while improving food security.

Sustainable biodiversity management, such as conserving forests, wetlands, and mangroves, is essential for preserving vital resources and supporting local livelihoods. Promoting traditional practices and diversifying activities economically contributes to household stability and adaptive capacity. Finally, migration is a proactive strategy for addressing resource degradation, allowing populations to seek better living conditions while bringing resources and skills to their home communities. Coherence between these elements is essential for developing integrated and sustainable adaptation strategies in Africa.

2.4. Gap identified

Recent literature on climate change highlights local knowledge’s crucial role in developing and implementing adaptation strategies, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, by providing a specific context often absent from standardized policies. For example, in Mali, traditional water resource management contributes to mitigating the effects of drought.

However, despite this growing recognition, most studies focus on specific regions, such as certain easily accessible rural or urban areas, leaving aside regions such as the Cascades or the East, where reliance on local knowledge is also high. Indeed, little research has systematically analyzed how to concretely integrate this knowledge to improve the effectiveness of public interventions. Most studies are qualitative or descriptive, without empirical approaches or rigorous evaluations of the direct impact of this integration on community resilience or the success of adaptation policies.

This gap limits decision-makers’ ability to develop strategies tailored to local contexts. This study aims to fill these gaps by providing an in-depth analysis, through case studies, on how the integration of local knowledge can strengthen and optimize public policies for adaptation to climate change in Burkina Faso, by mobilizing a multidisciplinary approach and participatory methods to understand the dynamics better better better and identify effective levers for action in vulnerable rural areas.

3. Conceptual Framework of the Research

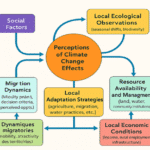

The conceptual framework, integrating the perception of climate change and socio-ecological dynamics, synthesizes the framework of the study and is presented in Figure 1 below.

4. Methodological Framework

4.1. Chosen approach

In order to obtain a thorough and nuanced understanding of the topic, the methodological approach adopted in this study is based on a mixed strategy, i.e., an approach combining both qualitative and quantitative methods. The qualitative approach allowed exploring the perceptions, practices, and social dynamics of the populations concerned, notably through semi-structured interviews, focus groups, and participatory observations. These techniques provide the opportunity to collect rich, detailed, and contextualized data, essential for understanding the complexity of the interactions between local knowledge, adaptation to climate change, and natural resource management.

The quantitative component allowed us to collect numerical data on key indicators such as the frequency of climatic events, the diversity of sustainable forest resource management practices, and the level of access to resources. Adopting the mixed-methods approach allowed us to triangulate the data, thus strengthening the credibility and validity of the results. It also facilitated the articulation between statistical and thematic analyses derived from qualitative data, for a comprehensive and coherent understanding of the phenomenon studied.

In addition, this approach provided methodological flexibility adapted to the complexity of the rural context and the multidimensional challenges linked to climate change. The combination of the two approaches thus provided solid evidence, while respecting the wealth of local knowledge and experiences, contributing to the development of relevant recommendations adapted to the realities on the ground.

4.2. Tools used

To carry out this study, several methodological tools were used to collect, analyze, and interpret data effectively. These included semi-structured interviews, which helped to deepen understanding of the perceptions, practices, and experiences of local stakeholders, providing them with a space for free expression while guiding the discussion on key themes related to adaptation to climate change and natural resource management. Structured questionnaire surveys were also administered to a sample of the population concerned, which made it possible to collect precise quantitative data on specific indicators such as the frequency of climatic events or sustainable management practices.

Content analysis, meanwhile, was used to process and interpret data from interviews and documents, identifying recurring themes, representations, and social dynamics. Also, participatory observations were conducted to capture behaviors and interactions in their natural context, ensuring a detailed and contextualized understanding of the local reality. These combined tools made it possible to obtain a comprehensive and triangulated vision of the phenomenon studied, reinforcing the robustness and credibility of the results.

Regarding the analysis tools, quantitative data was processed using statistical software such as Excel. For the qualitative data from the interviews, a thematic analysis was conducted using tools such as thematic matrices, allowing the identification of recurring patterns and social representations linked to climate change. In addition, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to contextualize the results, utilizing institutional reports, scientific studies, and local and regional documents. To ensure the reliability and validity of the research, a triangulation phase was incorporated, cross-referencing data from different sources to confirm or refute the hypotheses formulated.

4.3. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The research strategy is based on a structured, multi-step approach to select relevant sources to analyze climate change issues in Burkina Faso. The first step involves identifying key databases: Google Scholar, JSTOR, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and United Nations and World Bank reports, supplemented by the local Burkina Faso database to ensure contextualization. Then, keywords were defined to target key concepts such as “climate change in Burkina Faso,” “local perceptions,” “adaptation strategies,” and “community vulnerability,” to guide the literature search effectively.

Only French or English documents published between 1990 and 2025 were retained regarding the inclusion criteria. Sources must be academic journal articles, theses, reports from international organizations, or case studies, specifically relating to the Burkinabe context or similar areas in West Africa, and directly addressing the impacts of climate change on natural resources, livelihoods, and local communities. However, documents in languages other than French or English, those published before 1990, studies without direct reference to local populations or empirical data, or those relating to irrelevant geographical areas were excluded.

The selection process is carried out in several stages: an initial reading of titles and abstracts to quickly eliminate non-compliant sources, followed by a thorough evaluation of the methodology, results, and relevance of the conclusions to retain only high-quality works. Finally, a synthesis of the selected studies will identify trends, gaps, and recommendations to strengthen the understanding of the local impacts of climate change, in support of the development of decision-making tools and appropriate adaptation strategies.

4.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are essential to any research involving human populations and sensitive environments. In this study, in this thesis, particular attention was paid to respecting the confidentiality and anonymity of participants in this context we ensured that no data allowing their identification was disclosed without their informed consent and this by the recommendations of the Association for Ethical Research, all phases of the research were conducted by the principles of beneficence, ensuring that the benefits of the research were maximized while minimizing potential risks to participants(7). Particular attention was paid to obtaining ethical approval from the relevant committees at the local level, thus ensuring compliance with current standards and the legitimacy of the methods employed.

Furthermore, we adopted a participatory approach to actively involve the populations in the research process, providing them with clear and comprehensive information on the research objectives, methods, and possible uses. It is also essential to note that particular attention was paid at this level to respecting their autonomy by allowing them to give or withdraw their consent at any time during the study.

Also, awareness-raising and promotion of local knowledge and local languages were integrated into the approach to ensure a fair and respectful approach to social and cultural dynamics. These ethical considerations aim to guarantee the research’s credibility, legitimacy, and social responsibility.

4.5. Possible Limits

This research has limitations, particularly regarding geographical representativeness: it is mainly based on selected areas, which limits the generalization of the results to all vulnerable regions. The semi-structured surveys and interviews methodology also provides a rich qualitative perspective. However, it does not allow for longitudinal analyses or assessing the evolution of perceptions and strategies over time. The complexity of social, economic, and environmental dynamics could also benefit from a more in-depth interdisciplinary approach, integrating simulation models or indicators of community resilience, as proposed by researchers such as Folke et al.(8).

In conjunction with other work, this study reinforces the need for a holistic and participatory approach to strengthening local resilience to climate change. It is part of a current research that emphasizes the integration of local knowledge and social dynamics in the design of adaptation policies, while emphasizing that the success of these policies depends mainly on the capacity of institutions to coordinate, finance, and support these community efforts.

5. Results finding

5.1. Perception of climate variability and change

The study of local perceptions of climate change in different regions of Burkina Faso reveals a notable complexity, shaped by the wealth of traditional knowledge and the socio-environmental dynamics specific to each regional context. Taking the provinces of Comoé, Houet, and Mouhoun as a case study, this in-depth analysis highlights both the capacity of populations to perceive climate transformations as well as the repercussions of these transformations on natural systems, in this case, ecosystems and biodiversity, but also economic systems such as food security, livelihoods, or even market systems.

In Comoé province, particularly in the Cascades region or the Houet region in the Hauts Bassins region, communities have a system of traditional knowledge deeply rooted in their relationship with nature. The study shows that populations are susceptible to variations in agricultural cycles, such as early or late rainy seasons, which directly affect their livelihoods and food security.

The survey conducted in the Houet province shows that local populations perceive changes in the agricultural calendar, adjusting their practices accordingly, such as exploiting non-timber forest products, diversifying income sources, or shifting harvest periods for tree and forest products. The study’s results show that the populations of the different regions covered by the study are insensitive to recognizing the increase in temperature.

However, these perceptions remain limited when capturing more global phenomena, such as rising temperatures or the increased frequency of droughts, which are not always directly perceptible or understandable locally. Often based on immediate experiences or anecdotes, perceptions of these phenomena can thus be biased or incomplete, limiting their ability to anticipate or adapt effectively to long-term impacts. It should be noted that the municipality of Zitenga, for its part, illustrates a perception firmly rooted in the direct experience of climatic hazards, such as soil degradation or the decline of vegetation cover.

These populations have developed adaptation strategies based on traditional practices, such as community water management or the selection of resilient crop varieties. However, while valuable, this knowledge faces limitations when addressing more complex phenomena, such as resource scarcity. Local perceptions then tend to be fragmented or reductive, which can limit the relevance of adaptation strategies if scientific analyses and a thorough understanding of the mechanisms at play do not reinforce them.

Beyond perceptions, the tension between local knowledge and scientific approaches raises critical issues concerning legitimacy, recognition, and integration into public policies. The challenge is to ensure climate governance that values the plurality of knowledge while avoiding the marginalization or domination of one body of knowledge over another. The successful integration of these different forms of knowledge requires establishing truly inclusive participatory mechanisms, where the co-construction of adaptation strategies becomes a reality. It also requires a flexible institutional framework capable of evolving according to local contexts, while respecting cultural and socioeconomic diversity.

Therefore, the negotiation between modernity and tradition must be considered a dynamic process, likely to generate unexpected effects such as cultural resistance or the progressive loss of ancestral practices. These factors likely compromise social cohesion and resilience in the long term.

5.2. Knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystems

The results of this research highlight the richness and complexity of local knowledge regarding biodiversity and ecosystems in several regions of Burkina Faso, particularly in the provinces of Comoé and Houet. These territories, characterized by significant ecological diversity, offer a relevant field of study to understand how indigenous populations perceive and interpret environmental dynamics linked to climate change, while highlighting the crucial role of their traditional knowledge in natural resource management. In particular, their in-depth knowledge of plant and animal species, often transmitted orally from generation to generation, constitutes an intangible heritage of inestimable value for ecosystem conservation and sustainable management.

In the Comoé, Léraba, and Houet provinces, populations living near classified forests have developed a particular expertise in local flora. Through their empirical experience, these populations have observed that these trees tend to become fewer in number or show signs of degradation, which allows them to warn about the effects of climate change and human pressure on their environment. In the province of Houet, the perception of threatened species is also based on a detailed knowledge of behaviors and biological cycles. For example, local farmers and herders have noted a gradual decline in particular species, associated with the scarcity of rainy seasons or rising temperatures.

However, these perceptions can conflict with scientific data, highlighting more complex causes that are often difficult for these populations to perceive directly. This discrepancy can lead to inadequate conservation strategies, focused on specific species or issues, without considering integrated ecosystem management. Moreover, the oral transmission of this knowledge, vulnerable to cultural heritage bias or degradation, limits its systematicity and integration into public policies.

In the commune of Zitenga, located in the Central Plateau region, local knowledge of species also constitutes an important resource for conservation. Residents observed, for example, that particular species of baobabs and other trees with utilitarian uses appeared resilient to the effects of climate change; they also identified threats such as deforestation and overexploitation of resources. However, valorizing and integrating this knowledge into environmental governance raises major political and ethical issues.

On the one hand, there is a strong temptation to consider this knowledge a simple complement to scientific approaches, which risks reinforcing a dualism between indigenous and academic knowledge. On the other hand, implementing conservation policies based on these perceptions can provoke social resistance if they do not consider local socioeconomic issues, such as the need to ensure livelihoods for populations. For example, under the pretext of their protection, restricting the cutting or exploitation of particular species could generate marginalization or opposition, or even active resistance against conservation policies.

Furthermore, a purely targeted approach to endangered species without broader consideration of integrated ecosystem management could lead to piecemeal and unsustainable interventions. Effective conservation must rely on critical dialogue, in which a reflection accompanies recognizing local knowledge on global socio-environmental issues. Such an approach would help avoid the reproduction of contradictions, such as underestimating real threats or public distrust of policies perceived as imposed from outside.

Building truly inclusive environmental governance also requires creating participatory mechanisms where local populations, at the center of decision-making processes, can co-construct strategies adapted to their specific context. This requires constant vigilance about undesirable effects, such as marginalization, the loss of traditional practices, or the deterioration of the social fabric, which could compromise the sustainability of the actions undertaken.

5.3. Perceptions and strategies to strengthen the resilience of systems (natural and economic) to the effects of climate change

The analysis of risk perceptions by local stakeholders in the Cascades, Hauts Bassins, and Plateau Central regions highlights the complexity of the social and environmental dynamics underlying the development of climate hazard adaptation strategies.

While this approach helps identify relevant levers for action, particularly by strengthening local ownership of initiatives and adapting policies to cultural realities, it also reveals several contradictions and limitations requiring in-depth critical analysis. Indeed, integrating local knowledge into risk management must consider the diversity of cultural perceptions and representations that shape community engagement. One of these significant limitations concerns the traditional perception that certain risks, such as drought or flooding, are “natural,” “inevitable,” or “the work of God.”

These representations, deeply rooted in local cosmogony, can minimize the severity of these phenomena or attribute divine or ancestral origins to them, which limits the perception of their modifiable or predictable nature. For example, suppose local actors consider this calamity divine will or punishment in drought. This can reduce their motivation to adopt preventive practices or support technical resource management policies.

This worldview can lead to passive acceptance of risks, thus increasing their long-term vulnerability. Moreover, these beliefs, often difficult to challenge, hinder the implementation of constructive dialogue between populations and institutional decision-makers, limiting the co-construction of innovative adaptation strategies.

This cultural perception influences the design and implementation of public policies. For example, in some villages, creating forest plantations or sustainable management projects is perceived as an intrusion into sacred or community spaces or a potential threat to the traditional social order.

When conservation or development policies do not consider these representations, they risk generating resistance, active rejection, or a “passive resistance” where communities formally accept the measures without truly committing to them. These contradictions highlight the need to adopt governance sensitive to cultural representations while promoting intercultural dialogue. The co-construction of strategies must integrate these symbolic dimensions to ensure their acceptability and sustainability.

The risk of unexpected outcomes or adverse effects of these strategies must also be considered. For example, in the upper watersheds, community awareness of the impacts of climate change has led to the implementation of local forest management or economic diversification initiatives. While these actions have often strengthened the sense of autonomy and mobilized local stakeholders, they can paradoxically lead to reduced pressure on authorities or less attention to systemic issues such as land insecurity or weak infrastructure.

5.4. Perception, availability, accessibility, and adaptation strategy

Perceptions of environmental issues vary considerably across Burkina Faso, reflecting distinct socio-environmental and cultural realities. Environmental awareness is relatively developed in the Cascades region, characterized by extensive forest cover and a humid climate, largely thanks to community resource management and traditional knowledge passed down from generation to generation. This local involvement has enabled populations to develop a critical perception of deforestation, particularly about firewood harvesting and deforestation for extensive agriculture.

Nevertheless, this perception sometimes remains optimistic about the possibility of preserving these resources in the face of increasing pressure from commercial and illegal logging, reflecting an underestimation of the real issues. Valued community management often masks a profound vulnerability to expanding extractive activities, contributing to ecosystem degradation. This contradiction underscores the need to integrate a critical assessment of local perceptions to avoid overly optimistic management that could delay the implementation of coherent measures.

In the Central Plateau, environmental perception is often shaped by immediate experiences of dwindling natural resources and increased demographic pressures. These populations recognize certain ecological risks, such as erosion or soil degradation. However, their perception remains limited by a lack of information or a short-term vision focused on daily survival.

This gap between perceived awareness and long-term capacity for action complicates implementing sustainable adaptation strategies. This dissonance can lead to underestimating future risks, which hinders the collective mobilization needed to address global issues such as climate change. The strategies’ weakness also results from a lack of institutional framework and a deficit of objective information, which limits their effectiveness.

In the Hauts Bassins region, a moderate perception of environmental issues, influenced by the relative availability of resources, can also generate an attitude of complacency, or even carelessness, in the face of the progressive degradation of ecosystems. This partial perception limits the pressure exerted on authorities to implement sustainable management policies, accelerating resource deterioration. The contradiction lies in this ambivalent awareness: while degradation is perceived, it is not always accompanied by a desire for concrete action, compromising the sustainability of adaptation strategies.

A significant limitation of this approach lies in the qualitative nature of perceptions collected during surveys or interviews, which social or cultural biases can influence. For example, rural women’s perceptions of access to forest resources are often underestimated, even though they are central to their management.

Moreover, these perceptions do not always reflect actual resource availability, which fluctuates depending on the season, the intensity of exploitation, or the effects of climate change. Therefore, optimistic perceptions in the Cascades, for example, may mask a gradual reduction in resources over the long term, complicating the design of appropriate and effective policies.

Regarding the local strategies deployed, they often present contradictions and limitations. In the Cascades, community management and protected areas are perceived as effective in preserving biodiversity; however, their implementation can conflict with immediate economic needs, particularly regarding firewood or agricultural land.

These restrictive measures can give rise to social resistance or conflicts over use, particularly when populations perceive these initiatives as disconnected from their economic realities. In the Upper Basin, economic diversification through the promotion of crafts or trade is encouraged.

However, this approach remains limited by difficult access to markets, lack of training, and lack of infrastructure. Moreover, favoring short-term strategies, such as the unsustainable harvesting of forest resources, can paradoxically increase long-term vulnerability by further weakening ecosystems. The tension lies in the fact that these strategies, although effective in the short term, risk increasing overall vulnerability if coherent and integrated public policies do not support them.

In the context of the Central Plateau, demographic pressure and rapid urbanization often limit the effectiveness of traditional strategies, such as crop rotation or local reforestation, as they do not fully address global challenges such as soil degradation or climate change. Implementing structured public policies capable of supporting more integrated and sustainable solutions is becoming urgent.

Communication and awareness-raising must be strengthened: environmental education programs can help align local perceptions with ecological reality, while avoiding complacency in the face of degradation. Integrating local knowledge into policymaking, particularly by valuing the role of women and considering social diversity, could reduce these contradictions and promote strategies adapted to each context. Recognizing the central role of local actors in resource management is essential to ensure a participatory and sustainable dynamic in the face of complex environmental challenges.

5.5. Impacts of climate change on natural and economic systems and migratory dynamics

The effects of climate change, such as increased extreme weather events and ecosystem degradation, profoundly disrupt many communities’ living conditions. Faced with food insecurity, loss of livelihoods, and growing climate-related uncertainty, a significant portion of the population is forced to migrate to more vulnerable or safer areas. While urban areas often appear as refuges, offering better economic opportunities and relative stability, this migratory dynamic also creates new challenges, including rising inequality, increased pressure on resources, and weakening the social fabric.

However, this reality raises a significant contradiction in current adaptation policies. Indeed, climate migration is still too often perceived as a secondary or temporary consequence, rather than as a structuring factor to be fully integrated into resilience strategies. The explicit integration of these migrations into the design of adaptation policies is essential. Migration must be recognized as a response to climate change and as a central component of socio-territorial dynamics, allowing for the design of more coherent, proactive, and sustainable strategies.

Focusing policies on managing immediate impacts without anticipating these flows limits their effectiveness and neglects the possibility of transforming these challenges into development opportunities. For example, integrating migration into resilience paradigms allows for better resource allocation planning, territorial governance improvement, and anticipation of changing urban or rural infrastructure needs.

This gap between the recognition of the migratory phenomenon and its effective management is also apparent in the urban context, where rapid and unplanned urbanization risks transforming these refugee areas into spaces of increased precariousness. Therefore, policymakers must adopt a systemic approach to urban adaptation that can strengthen the resilience of territories to these flows by promoting more flexible, integrated, and inclusive governance. Therefore, implementing territorial cooperation mechanisms and harmonizing strategies between rural and urban areas is necessary to develop appropriate responses to future climate challenges.

Climate migration planning must shift from a reactive perspective to a proactive one. Migratory planning must become an integral part of global policies, recognizing migration as a transitional or permanent stage, but always as an integral part of development and adaptation processes. This requires rethinking development models, making governance more flexible, and promoting cooperation between local, national, and international actors. Recognizing this migration as a factor of civic and territorial transformation is a lever for developing more inclusive, resilient, and equitable strategies capable of effectively responding to future crises.

It is imperative to move beyond a fragmented and reactive view of migration flows to address the growing challenges of climate change. An integrated adaptation policy that places migration at the heart of resilience strategies will reduce the vulnerability of populations and transform these challenges into opportunities for sustainable territorial development. The key lies in more flexible, cooperative, and proactive territorial governance to ensure a coherent and equitable response to the accelerating global climate crisis.

6. Discussion

6.1. Perception of climate variability and change

The in-depth study of local perceptions of climate change in several regions of Burkina Faso, including Comoé, Houet, and Zitenga, provides valuable insight into how communities perceive and interpret these phenomena, while illustrating the complexity of socio-environmental dynamics specific to each territory. These results are part of a broader framework of studies conducted in Africa, where the perception of risks related to climate change also reveals substantial geographical, cultural, and socioeconomic diversity.

For example, Nyong Princely Awazi showed that in the Sahel region, communities mainly perceive droughts and soil degradation as phenomena directly linked to their agricultural activities(9). However, their ability to perceive global causes such as climate variability remains limited. Similarly, rural populations in the southern region of Kenya often intuitively perceive climate change, such as shifting seasons or increasing water scarcity. However, their understanding of the underlying scientific mechanisms remains superficial, limiting their ability to anticipate long-term impacts effectively 10.

The findings from Burkina Faso are consistent with this general trend observed in Africa, where risk perceptions are often based on immediate experience and traditional practices, such as community water management, crop diversification, or the exploitation of non-timber resources. However, these perceptions also have limitations, notably their inability to capture more global phenomena such as rising temperatures or the increased frequency of droughts, which are not always directly perceptible or locally understandable.

Biased or incomplete perceptions of these risks can lead to partially effective adaptation strategies or counterproductive actions without in-depth scientific information. For example, in the Cascades region, where forest cover is significant, people often have an optimistic view of their ability to preserve their resources. However, the increased pressure from illegal logging, often not perceived locally as an immediate threat, weakens their environment in the long term 11.

Regarding recognizing and promoting these perceptions in public policymaking, numerous African studies show a constant tension between indigenous management and external governance. As highlighted by Agrawal, the successful integration of local knowledge into climate governance requires inclusive and flexible participatory mechanisms capable of respecting cultural diversity while ensuring scientific legitimacy(12).

In Egypt, for example, Shammin, M.R. et al showed that cooperation between rural communities and local authorities can strengthen resilience to climate challenges, provided these processes are carried out in a participatory framework that respects local knowledge(13). However, the negotiation between modernity and tradition, often conflicting, can lead to cultural resistance or the gradual loss of ancestral practices, constituting an essential resource for local resilience(11).

6.2. Knowledge of biodiversity and ecosystems

The results of this study highlight the richness and complexity of indigenous knowledge regarding biodiversity and ecosystems in several regions of Burkina Faso, particularly in the provinces of Comoé and Houet. These territories, characterized by significant ecological diversity, constitute essential fields of investigation for understanding how local populations perceive, interpret, and react to environmental dynamics linked to climate change.

Indeed, this traditional knowledge, often transmitted orally from generation to generation, forms an intangible heritage of great value for the conservation and sustainable management of natural resources. Nygren, A., emphasizes that this knowledge, integrated into local culture, plays a crucial role in constructing social representations of environmental issues, but presents limitations when confronted with more complex global phenomena(14).

In the Cascades region, for example, populations living near classified forests have developed particular expertise on local flora. According to the study by Kaboré et al(15), these communities have observed, through their empirical experience, that certain trees, such as shea or néré, tend to become less numerous or to show signs of degradation, which allows them to perceive the impacts of climate change and anthropogenic pressure indirectly.

Similarly, in the Houet province, the perception of threatened species is based on a detailed knowledge of biological cycles and species behaviors, such as flowering or migration, often linked to the scarcity of rainy seasons or increasing temperatures, as confirmed by the work of Tapsoba(16).

However, these perceptions can come into tension with scientific data, highlighting more systemic and global causes, such as large-scale deforestation or soil degradation, which are difficult for local populations to perceive directly. This mismatch may lead to inappropriate management strategies focused only on specific issues or species instead of adopting integrated ecosystem management, as Berkes advocates(11).

Furthermore, the oral transmission of this knowledge, vulnerable to cultural degradation or social bias, limits its systematicity and recognition in formulating public policies. In the commune of Zitenga, located in the Central Plateau region, local knowledge of species, such as the baobab or other multi-use trees, constitutes a valuable resource for conservation, but also a source of tension when mobilized in a context of environmental governance. The valorization of this knowledge raises important political and ethical issues.

According to Agrawal, its integration must go beyond a utilitarian approach, and its cultural and symbolic dimension must be considered to avoid the reproduction of dualism between indigenous knowledge and scientific knowledge. The implementation of conservation policies, if it is not based on a truly participatory dialogue, risks reinforcing social resistance(12). For example, restrictions on logging or harvesting, perceived as a threat to subsistence or as an attack on traditional practices, can provoke opposition and forms of passive resistance(17).

Also, a targeted approach to threatened species can lead to piecemeal and unsustainable interventions without broader consideration of integrated ecosystem management. Effective conservation requires critical dialogue, where recognition of local knowledge must be accompanied by in-depth consideration of global socio-environmental issues to avoid underestimating real threats or causing distrust among populations in the face of policies perceived as imposed from outside.

Inclusive environmental governance must also promote the co-construction of strategies that actively involve local populations, particularly those often marginalized, such as women or young people, who play a central role in natural resource management(11). Vigilance is necessary to prevent undesirable effects such as marginalization, the loss of traditional practices, or the degradation of the social fabric, which could compromise the sustainability of the actions undertaken.

6.3. Perceptions and strategies to strengthen the resilience of natural and economic systems to the effects of climate change

The analyses presented for the Cascades, Hauts Bassins, and Plateau Central regions of Burkina Faso highlight complex social and cultural dynamics, including the perception that certain climate risks, such as drought or flooding, are “natural,” “inevitable,” or “works of God.” These observations resonate with previous literature on Africa, where perceptions of environmental risks are often deeply rooted in symbolic and religious frameworks.

For example, Sarr, in his study of climate risk management in West Africa, highlights that many communities perceive drought as divine punishment or a manifestation of ancestral anger, which limits their motivation to adopt preventive practices(18). Similarly, Diop et al. have shown that in several Sahelian regions, these cultural representations reinforce an attitude of passive acceptance in the face of climate hazards, increasing collective vulnerability(19).

This trend is also confirmed by the work of Faaij, A., who analyzes how the divine or fatalistic vision of risks can inhibit the implementation of technical or innovative adaptation strategies 20. Sarr’s study also emphasizes the difficulty of introducing sustainable management or reforestation policies in contexts where these spaces are perceived as sacred or linked to ancestral beliefs(18). Consequently, the failure or passive resistance to these policies is due to a lack of information and a perceived incompatibility with local symbolic representations.

It should be noted that these perceptions can lead to perverse effects, including reduced pressure on authorities to implement systemic or structural measures. Falayi, Gambiza, and Schoon reported that when communities perceive their actions as sufficient to address risks in several regions of Southern Africa, they tend to disengage from broader governance initiatives, such as land regulation or infrastructure investments(21).

This dynamic has also been observed in the Burkinabe context, where local perceptions of autonomy or control over climate risks can reduce pressure on national or regional institutions, thereby weakening the overall governance of resource management.

6.4. Perception, availability, accessibility, and adaptation strategies

Analyses conducted in different regions of Burkina Faso, such as the Cascades, the Central Plateau, and the Hauts Bassins, illustrate a diversity of environmental perceptions that join and enrich the body of previous work in Africa, highlighting the complexity of socio-environmental and cultural dynamics.

Indeed, several African studies have documented that the perception of risks related to climate change and the degradation of natural resources is often rooted in symbolic, religious, or traditional frameworks, which directly influences how populations react and adapt(18). For example, in the Sahel region, Sarr showed that the perception that drought is a divine punishment limits the motivation to adopt preventive or technical practices, a phenomenon also confirmed in the Burkinabe context(18).

Moreover, the underestimation of fundamental issues, particularly in the face of the expansion of extractive activities or demographic pressure, is widely observed across the continent. In their work in Southern Africa, Glwadys Aymone Gbetibouo has thus highlighted that the ambivalent perception of ecological degradation often leads to weak political mobilization, contributing to increased vulnerability(22).

While it has helped anchor local awareness and increase ownership, community management also reveals its limitations, particularly when economic activities or resource exploitation conflict with conservation measures. The search for short-term solutions, as in the case of economic diversification strategies or community management, can also, paradoxically, aggravate long-term vulnerability if coherent public policies do not accompany it, as Lescuyer et al. show in their work in West Africa(23).

Regarding the contradictions mentioned, African literature highlights that local perception is often influenced by social, cultural, or economic biases, which can limit the effective implementation of adaptation strategies. For example, the central role of women in natural resource management is often underestimated, while their involvement is crucial for the success of initiatives 24.

Moreover, the perceived disconnect between perceptions and objective realities, particularly regarding the actual availability of resources, is also reported in several African studies. The need to integrate these perceptions into inclusive governance is often highlighted as an essential condition for strengthening the resilience of communities to environmental challenges, as demonstrated by Berkes(11).

Also, highlighting the risk of resistance or rejection of policies by populations, when the latter do not consider their cultural perceptions and representations, is consistent with the conclusions of numerous African studies. For example, in the study by Lebel et al., passive or active resistance to sustainable management measures is identified as a significant obstacle to the success of environmental policies in several African contexts(17).

Therefore, recognizing the central role of local actors, the valorization of indigenous knowledge, and active participation in the co-construction of strategies are key elements, as also stated by Berkes to ensure effective and sustainable governance in the face of the complexity of African environmental issues(12).

6.5. Impacts of climate change on natural and economic systems and migratory dynamics

The analyses presented highlight that the effects of climate change, including the increase in extreme weather events and the degradation of ecosystems, are leading to significant migratory movements disrupting socio-territorial dynamics in Africa. These findings are consistent with and enrich previous literature, highlighting that climate migration is not simply a secondary consequence but a central factor in African communities’ resilience and sustainable development(25). For example, in several studies in sub-Saharan Africa, climate-induced migration has been considered an adaptive response, allowing populations to survive in the face of food insecurity and loss of livelihoods 20.

However, this work also shows that the perception of migration as a transitory or accidental phenomenon often limits the integration of this issue into national and local adaptation policies(2). The literature emphasizes the need to move from a reactive approach to proactive management, where migration is seen as a lever for development and not just as a consequence to be suffered 26. In this sense, African research highlights that territorial planning, explicitly integrating the management of migratory flows, would make it possible to better anticipate infrastructure, social services, and economic development needs, particularly in rapidly expanding urban areas.

In addition, the issue of rapid and unplanned urbanization, often linked to climate-induced migratory flows, is a recurring challenge in Africa. The literature highlights that these migrations pressure poorly prepared cities, reinforcing socioeconomic and environmental vulnerability 27. Establishing more integrated, cooperative, and inclusive territorial governance mechanisms is essential for transforming these flows into opportunities for sustainable territorial development (Ibid). African research also emphasizes the importance of strengthening cooperation between local, national, and international actors to develop coherent, anticipatory, and equitable policies capable of responding to future challenges related to climate change(28).

7. Implications of the Finding for Tackling Climate Change

The analysis of the contribution of this study to the fight against climate change is structured around two principal axes: its capacity to enrich knowledge of the problem and to support the development of effective national and international policies.

7.1. Implications for understanding the problem and the effectiveness of public action on climate

Drawing on a multidimensional methodological approach, based on an interdisciplinary approach integrating sociology, economics, and environmental sciences, this work has shed light on the complex processes in vulnerable territories. It has thus generated knowledge that can constitute a solid basis for the design of decision-making tools, better adapted to the specific realities of the populations concerned. The results’ robustness, reliability, and consistency reinforce their relevance for developing local, regional, and national intervention strategies.

As part of its contribution to understanding the issue, this study highlights the complexity of the interactions between social perceptions, natural resource management, economic dynamics, and migratory flows at the local level. Identifying how people’s perceptions and interpretations influence their behavior, adaptation strategies, and natural resource management constitutes a significant contribution 29. The integrative approach makes it possible to establish nuanced links between these factors, revealing the interdependent nature of the issues.

It thus contributes to evolving understanding, often limited to technical or ecological aspects, towards a more holistic vision considering the climate crisis’s social and human dimension. In addition, by providing solid empirical knowledge, this research facilitates the design of decision-making tools, strengthening the effectiveness of public policies and intervention strategies, particularly in local or regional contexts(3). It also paves the way for better integrating local knowledge in designing responses to climate change impacts by being part of a participatory and inclusive governance dynamic 29.

7.2. Implications for climate diplomacy

The findings of this thesis have profound implications for strengthening climate diplomacy at the international level, highlighting the need to adopt an approach based on the recognition and valorization of local and indigenous knowledge. According to the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change(30), the integration of traditional knowledge into climate governance promotes a better understanding of local dynamics. It strengthens the legitimacy of mitigation and adaptation actions.

By fully incorporating traditional perceptions, representations, and knowledge into climate governance strategies, environmental diplomacy can thus promote cooperation that is more balanced, inclusive, and respectful of social and cultural dynamics. This participatory approach, in line with the work of Leiserowitz, also allows for the emergence of synergies between national, regional, and international actors, facilitating the implementation of agreements and partnerships(31) based on the sharing of knowledge and resources, as also advocated by the recommendations of the Paris Agreement.

This study highlights the need to design integrated and holistic strategies for public policies, promoting stronger coordination between institutional, local, and economic actors. The Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report emphasizes that sustainable management of natural resources, combined with inclusive governance, is essential to strengthen the resilience of vulnerable territories in the face of climate change(32). Considering interdependent dynamics, particularly between perceptions, resource management, and migratory flows, is crucial in developing effective policies.

These findings call for strengthening mitigation efforts by supporting agricultural, forestry, and resource management practices that reduce greenhouse gas emissions while increasing communities’ adaptive capacity. They also emphasize the importance of increasing investment in technical, financial, and institutional capacity building, in line with OECD recommendations, to develop public policies better adapted to local realities while being part of a global dynamic to combat climate change(33).

This research also contributes to guiding proactive climate diplomacy by promoting consultation and multilateral cooperation. It highlights the urgent need to adopt shared governance, which combines mitigation and adaptation, based on the active participation of communities, local actors, and international institutions. Implementing such strategies, similar to those encouraged by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change(34), is essential to address the growing challenges linked to the climate emergency, while respecting the diversity of knowledge and development trajectories.

8. Possible Contradictions or Tensions

Despite the many contributions of this study, certain contradictions or tensions can be identified, particularly between the valorization of local knowledge and the need to adopt global and standardized policies to address climate issues. Indeed, recognizing traditional knowledge can sometimes conflict with technocratic or centralized approaches, favoring universal solutions to the detriment of specific contexts.

Furthermore, implementing participatory and inclusive strategies can generate tensions between local actors, often poorly structured or marginalized, and institutional authorities, who may prioritize economic or political interests to the detriment of community aspirations. Finally, the tension between the speed of intervention required to address the climate emergency and the need for a participatory process, which is long and often complex, raises issues regarding the balance to be found between effectiveness and inclusiveness in climate action. These contradictions must be addressed to ensure balanced, coherent governance that is truly adapted to the realities on the ground.

9. Conclusion

By emphasizing the importance of fully integrating local dimensions and indigenous knowledge into the design and implementation of adaptation and mitigation strategies, this study significantly contributes to the fight against climate change. It highlights that the success of climate policies depends largely on participatory, coherent, and holistic governance capable of coordinating institutional, local, and economic actors while promoting social and cultural dynamics.

On a practical level, it is recommended to strengthen financial, technical, and institutional support for community initiatives, encourage inclusive multilateral cooperation, and adopt an integrated approach, considering the interdependencies between perceptions, resource management, and migration flows.

These recommendations aim to develop more effective policies adapted to local realities, while contributing to more equitable global climate governance. Future research could explore the impact of indigenous knowledge on the practical success of adaptation projects, analyze potential tensions between global and local approaches, or study the mechanisms of consultation between actors in different socioeconomic contexts. This work would deepen our understanding of the complex dynamics related to climate governance and optimize intervention strategies at all scales.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2023. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009157896/type/book

- Adger WN. Social Capital, Collective Action, and Adaptation to Climate Change. Economic Geography. 2003 Oct;79(4):387–404.

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009325844/type/book

- Rick de Satgé. Changement climatique, conflits et déplacements dans le Sahel. 2023; Available from: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/f7b65d87903d4169a719d0ea2f386a5f

- Ministry of the Environment and Living Environment. Situation of classified forests in Burkina Faso [Internet]. 2007. Available from: https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/bkf146620.pdf

- Dilling L, Lemos MC. Creating usable science: Opportunities and constraints for climate knowledge use and their implications for science policy. Global Environmental Change. 2011 May;21(2):680–9.

- Aline Shakti Franzke et al. Internet Research: Ethical Guidelines 3.0 Association of Internet Researchers [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://aoir.org/reports/ethics3.pdf

- Folke C, Carpenter SR, Walker B, Scheffer M, Chapin T, Rockström J. Resilience Thinking: Integrating Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability. E&S [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2025 Jul 20];15(4). Available from: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/art20/

- Nyong Princely Awazi. Drought recurrence in Africa’s Sahel region: nature-based adaptive solutions and implications for smallholders’ livelihoods. 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 20]; Available from: https://rgdoi.net/10.13140/RG.2.2.35456.20489

- Chemuliti Judith et al. Smallholder Farmers’ Perceptions and Responses to Climate Change in Multi-stressor Environments: The Case of Maasai Agro-pastoralists in Kenya’s Rangelands. 2017; Available from: https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/56096817/ajrd-5-4-4-libre.pdf

- Berkes F. Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management. 2009 Apr;90(5):1692–702.

- Agrawal A. The Role of Local Institutions in Adaptation to Climate Change [Internet]. World Bank, Washington, DC; 2008 [cited 2025 Jul 16]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/28274

- A Framework for Climate Resilient Community-Based Adaptation. In: Climate Change and Community Resilience [Internet]. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2022 [cited 2025 Jul 20]. p. 11–30. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-16-0680-9_2

- Nygren A. Local Knowledge in the Environment–Development Discourse: From dichotomies to situated knowledges. Critique of Anthropology. 1999 Sep;19(3):267–88.

- Kaboré F, Zabsonre Tiendrebeogo WJ, Sougué C, Zombré DMAF, Sompougdou C, Ouédraogo M, et al. Panorama des rhumatismes inflammatoires chroniques au Burkina Faso : bilan de 14 ans de pratique de la rhumatologie. Revue du Rhumatisme. 2021 Dec;88:A318–9.

- Tapsoba, A. Poverty, food insecurity and vulnerability of agricultural households in a large-scale irrigation system: The case of the Bagré irrigated perimeter in Burkina Faso [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://ur-green.cirad.fr/content/download/5400/39482/version/1/file/Th%C3%A8se+Tapsoba_Finale_2020.pdf

- LeBel EP, McCarthy RJ, Earp BD, Elson M, Vanpaemel W. A Unified Framework to Quantify the Credibility of Scientific Findings. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science. 2018 Sep;1(3):389–402.

- Sarr AB, Camara M. Evolution of Extreme Rainfall Indices by Analysis of Regional Climate Models from the CORDEX Program: Climate Projections for Senegal. ESJ. 2017 Jun 30;13(17):206.

- Institut Supérieur de Formation Agricole et Rurale (ISFAR), Université Alioune Diop de Bambey, Sénégal, Ndiaye M, Malick Diallo T, Laboratoire de Recherche en Economie de Saint-Louis (LARES), Université Gaston Berger de Saint-Louis, Sénégal. Impact des chocs agro-climatiques sur la sécurité alimentaire desménages ruraux au Sénégal. AfJARE. 2024 Mar 30;19(1):99–110.

- Faaij A. Modern Biomass Conversion Technologies. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change. 2006 Mar;11(2):343–75.

- Falayi M, Gambiza J, Schoon M. A scoping review of environmental governance challenges in southern Africa from 2010 to 2020. Envir Conserv. 2021 Dec;48(4):235–43.

- Glwadys Aymone Gbetibouo. Understanding Farmers’ Perceptions and Adaptations to Climate Change and Variability: The Case of the Limpopo Basin, South Africa. 2009; Available from: file:///C:/Users/LAPTOP/AppData/Local/Temp/MicrosoftEdgeDownloads/6311ca77-fdd6-4d99-b2e8-8e7fc3061723/8531.pdf

- Lescuyer G, Mvongo-Nkene MN, Monville G, Elanga-Voundi MB, Kakundika T. Promoting Multiple-use Forest Management: Which trade-offs in the timber concessions of Central Africa? Forest Ecology and Management. 2015 Aug;349:20 8.

- Benewindé Jean-Bosco Zoungrana, Kouka Ouedraogo. Regional Approach to Adaptation to Climate Change in Burkina Faso [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://napglobalnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/napgn-en-reginal-approach-climate-change-adaptation-burkina-faso.pdf

- Black R, Adger WN, Arnell NW, Dercon S, Geddes A, Thomas D. The effect of environmental change on human migration. Global Environmental Change. 2011 Dec;21:S3–11.

- Rigaud, Kanta Kumari et al. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/29461

- Tacoli et al. Urbanization, Rural–Urban Migration and Urban Poverty. [Internet]. 2015. Available from: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/our_work/ICP/MPR/WMR-2015-Background-Paper-CTacoli-GMcGranahan-DSatterthwaite.pdf

- Rigaud et al., Roundwell : preparing for internal climate migration (Vol. 2 of 2) : Main report [Internet]. 2018. Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/846391522306665751

- Moser SC, Dilling L. Communicating Climate Change: Closing the Science‐Action Gap [Internet]. Oxford University Press; 2011 [cited 2025 Jul 20]. (Oxford Handbooks Online). Available from: https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/28186/chapter/213097621

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022 – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Internet]. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009325844/type/book

- Leiserowitz A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Climate Change. 2006 Aug 21;77(1–2):45–72.

- Díaz S, Demissew S, Carabias J, Joly C, Lonsdale M, Ash N, et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework — connecting nature and people. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. 2015 Jun;14:1–16.

- OECD. Budgeting and Public Expenditures in OECD Countries 2019 [Internet]. OECD; 2019. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/budgeting-and-public-expenditures-in-oecd-countries-2018_9789264307957-en.html

- UNFCCC. Report of the subsidiary body for scientific and technological advice on its sixteenth session, held at Bonn, from 5 to Jun 14 2002 [Internet]. 2002. Available from: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/docs/2002/sbsta/06.pdf