ABSTRACT

| No Vietnamese companies studied within our samples have registered a net-zero target with the Science Based Target initiative (SBTi). In general, this paper explores contradictions in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices, and using Vietnam as a case. It highlights a growing gap between corporate ESG acknowledgment and actual performance through a narrative literature review and analysis of data from global organizations, and Vietnam’s Top 100 Sustainable Companies (CSI2024) and TOP50 Corporate Sustainability Award companies (CSA2024). Results show that many Vietnamese firms prioritize public recognition over authentic sustainability efforts, posing challenges to effective ESG integration. Recommendations include global ESG standardization, mandatory third-party reporting, and inclusive governance to align with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) promoting robust business practices. Significant regulatory harmonization is needed to resolve ESG contradictions and achieve genuine sustainability. | |

1. Executive summary

Contradictory demands increase when organizational environments grow more dynamic, global, and competitive. Scholars and professionals are increasingly using a paradox lens to comprehend and explain these conflicts. This article analyzes the intrinsic conflicts within Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks, emphasizing their evolution and use in Vietnam’s expanding market.

ESG originated from concepts of sustainable development, exemplified by the Brundtland Report of 1987, and was formalized in 2004 with the UN’s “Who Cares Wins” report. It currently faces challenges such as trade-offs between profitability and sustainability, discrepancies in ratings, and the potential for greenwashing. Just 25% of CSI2024 corporations release verified sustainability reports, while 31% of CSA2024 companies do the same.

The research employs a narrative literature analysis to assess the conformity of CSI2024 and CSA2024 enterprises with SBTi and the clarity of their reporting. Successful examples such as Unilever and Patagonia address grievances and demonstrate the effective use of ESG principles. Policy suggestions include making global ESG standards more consistent, strengthening Vietnam’s Decree 08/2022/ND-CP[1] by requiring independent verification and green audits, and ensuring that SDGs 8, 12, and 13 align.

2. Introduction

The word “sustainability” originates from the Latin term sustinere. Hans Carl von Carlowitz first mentioned the concept of sustainable harvesting in 1713. As a mining manager in the German region of Saxon Erzgebirge, he was in charge of supplying raw materials to the mining sector, which included timber. According to Carlowitz, logging should only be done sustainably, at a level that permits the forest to recover and regenerate.[2] In the 1970s, sustainability became a well-defined and acknowledged idea that included social, environmental, and economic factors.

In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development, chaired by Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, published a report titled “Our Common Future”.[3] Commonly known as the Brundtland Report, this landmark document suggested that creating existing environmental institutions in isolation was insufficient because ecological issues were integral to any sustainable development policy.

The Brundtland Report asserted that the leading causes of severe ecological problems worldwide are poverty in less developed countries and unsustainable production and consumption practices in developed countries. Before that, “The Limits to Growth”, a report to the Club of Rome, represents a pivotal point in the theoretical discourse, emphasizing the shift from economic growth to economic development.[4] First published in 1972, the report’s core message remains relevant today, arguing that even with advanced technology, the world’s interconnected resources or the global natural system in which we all live may not be able to sustain the current level of economic expansion and meet the needs of the world’s growing population, expected to reach 9 billion by 2050.[5] The concept of Sustainable development was then defined by the United Nations (U.N) in 1987 as: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”[6]

Carbon dioxide (CO2) accounts for about 60% of human-induced global warming, due to its significant annual emissions exceeding 30 Gt CO2. [7] For thirty years, global warming and climate change have been debated among scientists, researchers, lawmakers, policymakers, and members of civil society from various international backgrounds.[8] The 2023 U.N. Climate Change Conference, COP28, did not explicitly endorse a “phase-out” but did make a significant commitment to “transition” from fossil fuels to cleaner alternatives, especially renewable energy. The joint communiqué characterizes “the fossil energy transition” as the discontinuation of coal usage and the achievement of net-zero emissions by 2050. Swift abolition of fossil fuel subsidies is imperative.[9]

Two urgent challenges that need rapid attention in contemporary society are socioeconomic inequality and global warming, sometimes called climate change. ESG, the corporate sustainability concept and framework, was born to tackle these existential threats to human beings.

3. Research methodology

This study adopts a two-phase qualitative approach to seek and elucidate the paradoxes and gaps of ESG within corporate governance practices. First, a broad narrative literature review approach to explore the historical evolution, paradoxes, and practical implications of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) frameworks within corporate sustainability practices.

Unlike a systematic literature review, which adheres to rigid protocols for exhaustive searches and quantitative synthesis, a narrative review allows for a more interpretive and conceptual synthesis of key themes, drawing on seminal works, historical documents, and critical analyses to elucidate contradictions in ESG application. This method is particularly suitable for the thesis’s focus on theoretical paradoxes and contextual challenges, such as those in emerging markets like Vietnam, where empirical data may be limited. The review is guided by the research objective of clarifying ESG’s ambiguities and proposing pathways for improved integration. Second, and more focus is, an explorative study of, and through documentation analysis method, will examine the sustainability practices of TOP100 CSI2024 and TOP50 CSA2024 to identify gaps between promotion and performance in reality.

3.1 Justification for document analysis

Document analysis is the process of examining and interpreting existing documents, including books, reports, articles, letters, legal texts, and various other written materials. This is not a “passive” method and does not lack empirical evidence, which is common outdated assumption, but a proactive and systematic process that requires critical thinking and interpretation from the researcher. Although descriptive, according to Scott, the value of a document should be evaluated based on four criteria: authenticity, credibility, representativeness, and meaning. Applying these criteria ensures that the extracted data is valid and can be used to draw sound conclusions.[10]

Many reputable scholars have demonstrated the utility of this method. Yin, in his classic work on case study research, emphasizes that document analysis is a crucial source of evidence that complements and corroborates other data sources like interviews and observations.[11] Furthermore, Bowen has argued that document analysis can be a stand-alone research method capable of producing reliable research outcomes. She asserts that “document analysis can be a primary or supplementary research method, providing richness to qualitative studies”.[12]

This method is particularly effective for studying past phenomena or issues where direct data collection is difficult. For instance, research on historical public policies would be impossible without archival documents. Humans currently inhabit an era characterized by an abundance of information and an overwhelming availability of business materials to the public. Thus, document analysis allows researchers to access a vast amount of data in a time and cost-efficient manner, helping to uncover trends, patterns, and relationships that other methods might miss.

3.2 Research design

The study adopts a qualitative and conceptual design, prioritizing thematic exploration over empirical testing. It integrates historical analysis, theoretical critique, and policy recommendations to address the core question: How do paradoxes in ESG undermine its effectiveness as a sustainability tool? Key themes such as the tension between profit maximization and long-term sustainability, inconsistencies in ESG ratings, and limitations of compliance-driven approaches are identified through a hybrid deductive-inductive approach. This method draws deductively on foundational ESG literature (e.g., CSR evolution) and inductively refines insights through iterative analysis of emerging critiques (e.g., greenwashing risks), ensuring a balanced examination of established and novel perspectives.

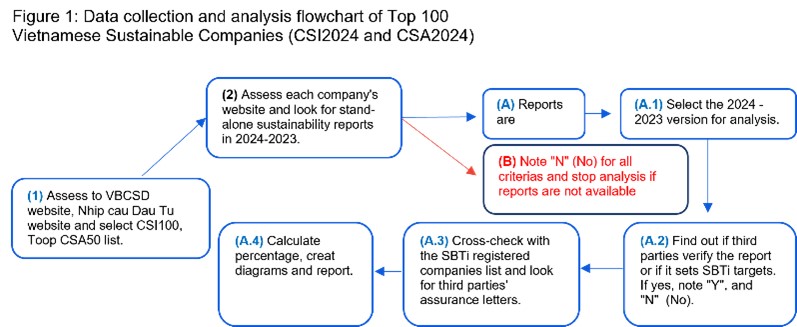

To enhance the study’s validity, a documentation analysis will examine the sustainability practices of Top 100 Vietnamese Sustainable Companies (CSI2024). This analysis will assess how these businesses implement sustainability beyond their awards, focusing on tangible evidence of their commitments. The analysis will involve reviewing corporate sustainability reports, certifications, and public disclosures. Key research questions include:

- How many of these companies are registered with the Science Based Target Initiatives (SBTi)?

- Do these companies publish sustainability reports?

- Are these sustainability reports verified by third parties?

This documentation analysis will provide practical insights into the real-world application of ESG principles, complementing the study’s conceptual exploration of ESG paradoxes.

3.3 Data sources and collection

Data were sourced from a purposeful selection of academic, institutional, and practitioner materials to ensure comprehensiveness and relevance. Primary sources include:

- Historical and foundational reports: The Brundtland Report (1987), “The Limits to Growth” (1972), “Who Cares Wins” (2004), and UN Global Compact documents (2000 onward).

- Scholarly works: Key theories from Archie B. Carroll (1979) on CSR, Alex Edmans on ESG as an intangible asset, Rajeev Peshawaria’s critiques in Sustainable Sustainability, and Kim Sekol’s ESG Mindset.

- Additional references: Publications on sustainable development (e.g., Hans Carl von Carlowitz, 1713), economic perspectives (e.g., Milton Friedman, 1970; Peter Drucker), and recent surveys (e.g., KPMG on CEO perceptions; IBM on sustainability spending; World Meteorological Organization on emissions).

- Contextual insights: Discussions on Vietnam’s ESG adoption, drawn from regional reports and general sustainability literature.

- Analyze the sustainability reports of CSI2024-awarded firms in Vietnam to identify gaps between recognized and actual ESG actions. Document analysis of the stand-alone sustainability report of the CSI2024, CSA2024-awarded firms in Vietnam uses terms such as “independent audit”, “third party verification”, “SBTi”, “third party verification”, or “assurance” to look for proofs of report quality. Data collection and analysis flowchart (figure 1) is as below:

Literature was collected through targeted searches in academic databases (e.g., Google Scholar, Scopus, Elicit…), books and firms’ reports from KPMG, PwC, Deloitte, using keywords such as “ESG paradoxes,” “sustainable development history,” “CSR evolution,” “greenwashing in ESG,” and “ESG in emerging markets.”

Inclusion criteria focused on relevance to ESG’s environmental, social, and governance dimensions, publication date (primarily 1970–present to capture evolution), and credibility (peer-reviewed articles, U.N. reports, books by recognized experts). Exclusion criteria omitted purely quantitative studies or those unrelated to corporate practices.

3.4 Why stand–alone report matters

Companies that publish independent CSR reports exhibit greater levels of corporate social responsibility than those that do not.[13] Stand-alone sustainability reports are frequently regarded as more thorough in regard to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors, as they enable companies to elaborate on sustainability-related metrics, objectives, risks, and advancements without the limitations imposed by an annual report structure. These reports frequently adhere to international frameworks like GRI (Global Reporting Initiative), offering comprehensive insights into environmental consequences, labor rights, diversity, and anti-corruption matters, catering to stakeholders’ requirements, including ESG investors, NGOs, and regulators.[14]

Sustainability reporting in Vietnam is progressing, as enterprises are progressively embracing international standards such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) framework.[15] Nonetheless, the quantity of firms generating sustainability reports remains constrained.[16] The prevalence of independent sustainability reports in Vietnam is limited due to high costs, inadequate regulatory guidance, and constrained resources of businesses.[17] The inadequate ESG reporting by Vietnamese firms is due to weak qualifications of accountants, management processes, and information technology systems.[18]

Sustainability reporting enhances business value, although its execution differs among Vietnamese enterprises.[19] A study by KPMG in 2024 indicates that approximately 46% of Vietnamese firms have included information on ESG and sustainability in annual reports.[20] However, in Vietnam, publicly traded companies reference “green talks” in their reports instead of integrating sustainability plans into their corporate operations.[21] Another recent study of PwC shows that only 10% of the companies studied in Vietnam have disclosed external assurance (APAC 49%), and merely 8% revealed net-zero aims, in contrast to 51% in the Asia-Pacific region.

None of the examined companies had published net-zero targets that were based on and confirmed by the SBTi.[22] This situation could undermine trust if the report is not independently audited or lacks transparency.

3.5 Triangulation

Triangulation is necessary to enhance research robustness. In this instance, besides CSI100, another dataset of the TOP50 Corporate Sustainability Awards (CSA2024)[23] will be examined and reported after omitting the duplicated firms. The analysis will utilize the same data collection and analysis methods outlined in section 3, figure 1 – Data collection and analysis flowchart.

3.6 Data analysis

No quantitative meta-analysis was conducted, as the study prioritizes conceptual exploration over statistical analysis (also mentioned in section 3.3). While non-numerical data is typically associated with qualitative research, there are instances where a percentage or a numerical value might encapsulate qualitative findings, as it reflects the assertion made by the researcher.[24]

Numerical data can be employed to record issues, characterize samples, and validate interpretations.[25] Interpretivist researchers may integrate qualitative analysis with quantitative measures to investigate differences between stated and actual schemas.[26] Numerical values enhance the precision of such assertions, leading to the coining of the term “quasi-statistics” for basic enumerations that substantiate phrases like “some,” “usually,” and “most.”[27] For example, the phrase “28% of the examined cases demonstrate that” is more robust and credible than “most of the group shows that…” due to its enhanced directness.

The documentation analysis will evaluate the extent of sustainability practices among the selected companies, incorporating minimal numeric reporting (e.g., the percentage of companies publishing sustainability reports) while emphasizing qualitative insights. This approach ensures that the analysis aligns with the study’s focus on conceptual themes, such as identifying potential greenwashing or limitations in compliance-driven sustainability efforts. In conclusion, the incorporation of numerical data is a valid and beneficial approach for qualitative researchers when utilized as a supplement to a comprehensive process-oriented research methodology.[28]

4. ESG’s historical and conceptual foundations

ESG, an acronym for environmental, social, and governance, denotes a framework employed to assess an organization’s social and ecological impact. It has recently become the focal point of global discourse on sustainable governance, management, and investment. In Vietnam recently, the terms “ESG”, “sustainability” and “sustainable development” are ubiquitous in newspapers, consulting firms, and seminars offering sustainable services and products.

4.1 From CSR to ESG

Notably, ESG has transitioned from a concept rooted in financial investing to a widely utilized governance term.[29] Nonetheless, ubiquitous mention does not equate to universal comprehension of its significance.[30] The notion of ESG is ambiguous and inadequately delineated.[31] Originating in sustainability reporting, its application and understanding vary significantly due to its vague and challenging nature.

Historically, ESG has improved the progressive idea of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), which Archie B. Carroll came up with and announced in 1979.[32] Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has a complicated and diversified history that began in the middle of the 20th century.[33] At this point, businesses recognized their greater obligations beyond making money, thanks to societal changes and people becoming more aware of social problems.

During the 1960s and 1970s, social movements that worked to protect the environment, women’s rights, and civil gained momentum. These movements changed people’s thoughts and made them more conscious of social and environmental issues. During this time, companies started to use ecological management methods because people were more worried about environmental issues and the government was paying more attention to them. Several businesses started putting out environmental reports that explained how their actions affected the environment and what they were doing to fix it. The first “socially responsible” investment funds were out during this time. These funds let investors leave out companies involved in controversial areas, like tobacco, guns, and companies involved in the Vietnam War.[34]

Carroll delineates four fundamental elements of corporate social responsibility, with profit being the foremost. The basic responsibility of a firm is to prevent financial losses, as such losses render it a burden on society. The second aspect is legal accountability: compliance with the law, honesty, and tax obligations constitute the basis for generating profit. The third is a moral duty to the environment and society, encompassing the preservation of fundamental human rights, safeguarding all species, and abstaining from the depletion of natural resources or the pollution of the environment for personal gain. The fourth obligation is to share a beneficent responsibility with society. Corporations must contribute to philanthropic endeavors with their legitimate profits and revenues.

4.2 Global milestones

The notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR) parallels sustainability with its foundational principles related to the societal obligations of corporations.[35] Nonetheless, sustainability is regarded as having a more limited focus on extensive ecological issues than those addressed in CSR, which, while encompassing ecological considerations, primarily highlights the social outcomes and impacts of the organization.[36] Within the ESG framework, sustainability includes a comprehensive definition that integrates normative principles, interdisciplinary scientific collaboration, and systems thinking in implementing organizational sustainability management.

Since its establishment in 1945, the UN has initiated and supported several endeavors concerning the global economy, development, environment, human rights, and associated commercial and market matters. In 1990, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan was tasked with formulating guidelines and suggestions to enhance the incorporation of environmental, social, and corporate governance considerations in asset management, securities trading services, and associated research initiatives.

The report received sponsorship from prominent global financial firms, including HSBC, Credit Suisse Group, Deutsche Bank, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and Henderson Global Investors.[37] In 1999, Secretary-General Kofi Annan expressed apprehension at the World Economic Forum in Davos regarding the potential for an escalating backlash against globalization from less developed nations, attributed to the swift expansion of globalization in the late 20th century and deficiencies in global governance concerning labor standards, human rights, and environmental protection. Kofi Annan (1999) warned that “globalization’s fragility requires businesses to adopt core values in human rights, labor, and environmental practices to ensure sustainable global prosperity.”[38]

A pivotal study entitled “Who Cares Wins,” 2005, coined the term “ESG.” ESG’s establishment was initiated by former Secretary-General Kofi Annan’s concerns about the instability of globalization and its vulnerability to substantial resistance from various sources, including nationalism, protectionism, populism, and terrorism. He urged corporations and trade associations to embrace, endorse, and disseminate fundamental ideals, including environmental policies, labor standards, and human rights.[39] The Global Compact, an international project established in July 2000 by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, joins businesses, UN agencies, labor unions, and civil society to uphold ten principles concerning human rights, labor conditions, environmental sustainability, and anti-corruption.[40]

The “Who Cares Wins” report was made in response to the U.N.’s demand for the effective use of economic prosperity for sustainable development. It connects financial markets to a changing world and advises the financial sector. The “Who Cares Wins” principle has been implemented in multiple domains, encompassing both corporate and social policy.[41] Companies that do well can increase shareholder value by getting ready for new rules, managing risks, or branching out into new areas, all while helping the community stay healthy. ESG ratings and indexes were initially utilized in the 2000s. Financial services firms have developed instruments to evaluate and assess enterprises based on their performance with environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria. This enables investors to examine companies’ ESG criteria and select their preferred investment options.

5. Challenges in ESG implementation

Similar to numerous other developing nations striving to align with global trends in contemporary ideas and technologies, it is prevalent for enterprises, particularly in Vietnam, to superficially and initially implement ESG practices without a comprehensive grasp of CSR concepts. Businesses must delineate the distinctions between concepts and comprehend the practical implications of ESG, rather than solely the theoretical framework. Corporate failures are associated with various factors, including inadequate management, uncontrollable crises, and the recurrent repercussions of failing to comprehend the principles and essence of the idea. Effectively executing sustainability principles and incorporating them into a company’s everyday operations presents considerable hurdles, particularly for local small and medium-sized firms (SMEs). Shallow practices may produce inaccurate outcomes, squander resources, and result in allegations of greenwashing. Lack of awareness and comprehension of sustainability among employees and stakeholders might impede sustainable growth.

5.1 Promotion over performance

“The good news is that everyone is talking about ESG. The bad news is that everyone is talking about ESG.” Said, Rajeev Peshawaria, CEO of Stewardship Asia Centre.[42] Sustainable development and ESG integration are transforming company models across sectors, propelled by stakeholder demands for transparency and ethical governance.[43] The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development offers a framework for a sustainable future, with ESG variables signifying strategic risks and possibilities for enterprises.[44] Linking the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to corporate sustainability and ESG issues necessitates an examination of double materiality, encompassing both stakeholder and financial materiality.[45] Research indicates that companies frequently implement ESG practices due to financial market pressures rather than as a sincere attempt to incorporate sustainability into their fundamental operations.[46]

Recent research underscores a divergence between ESG discourse and implementation in the investment sector.[47] ESG “washing” adversely affects business financial performance, indicating a discrepancy between ESG assertions and actual practices. Companies discuss climate issues more frequently during earnings calls when they are material; yet, this discourse is inversely correlated with actual changes in emissions, indicating that firms may engage in more rhetoric than action.[48] The quantity and quality of ESG reporting have increased; yet, ESG performance has stalled, indicating the need to emphasize the improvement of ESG results over mere reporting.[49]

For many firms, the prevailing perspective on sustainability is to generate a sustainable profit. They believe that without profit, the organization does not exist, so the top sustainability aspect of a firm is about generating profit, as the prominent economist Milton Friedman’s (1970) assertion: “The only corporate social responsibility a company has is to maximize its profits.”[50]

5.2 Profit Vs. Sustainability

Renowned management Guru, Peter Drucker, once said: “Profit for a company is like oxygen for a person. You’re out of the game if you don’t have enough of it. But if you think your life is about breathing, you’re missing something.”[51]While breathing is necessary for life, it is not the purpose of life. Similarly, profits are essential for a company to exist.[52]

Still, today, the shareholder-first ideology holds its grond strong. Recent studies on ESG investing indicate a nuanced correlation between sustainability and profitability. Some research reveal a favorable correlation between high ESG performance and firm value and profitability, while others suggest that ESG funds may emphasize financial returns over sustainability.[53],[54]

Despite decades of admonitions from the scientific community, numerous papers, and climate conferences, the globe remains misaligned in its trajectory.[55] ESG has been advocated as a sustainable governance instrument, although it has demonstrated a lackluster performance record. Notwithstanding the commitments of almost 20,000 major global corporations and 3,800 non-profit organizations to the UN Global Compact, emissions have not decreased but rise significantly with the growth of global GDP. A contributing issue is that business managers and staffs are incentivized to pursue objectives that optimize earnings and reduce expenses, leading to insufficient consideration of negative externalities. Emissions from the industry and energy sectors are the primary contributors to global growth.[56]

In 2022, carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations, the most significant greenhouse gas, exceeded 50% of pre-industrial levels for the first time and continue to rise despite United Nations appeals. Recent research from the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) indicates that greenhouse gas emissions persist in their increase, exhibiting no indications of abatement.[57]

The primary issue lies in distinguishing between “E,” “S,” and “G.” E and “S” present existential dilemmas that necessitate contemplation; however, “G” serves as a potential solution. From this viewpoint, “E” and “S” represent desired outcomes or objectives, while “G” serves as the method or strategy for attaining them.[58] Shareholder activism advocating for ESG enhancements can elevate firm ESG policies and financial outcomes.[59] The majority of sustainability issues stem from the “G” component.

5.3 ESG Vs. Iintangible assets

Businesses are shifting from physical to technology-based structures in the modern economy. A company’s valuation is mostly based on its brand, client base, talent depth, and other non-financial factors. ESG factors are essential for recognizing enterprises possessing sustainable competitive advantages, which are increasingly significant intangible assets.[60]

Although ESG disclosure often decreases carbon intensity, this impact is especially significant for companies possessing substantial intangible assets that influence a company’s valuation and prospective cash flow.[61], [62]

Alex Edmans, a professor of finance at London Business School, in his controversial article “The End of ESG”, has argued that ESG is both tremendously important and nothing special than other functions of a business.[63] According to Edmans, ESG is neither better nor worse than other intangible assets that produce long-term financial and social gains, such as management excellence, corporate culture, or innovation. Thus, his argument should be seriously taken into further discussion.

It is well-recognized that brand value constitutes a significant portion of a corporation’s intangible assets. Before the emergence of ESG, business secrets, patents, and brands were similarly substantial assets for a company. Integrating ESG factors into business and organizational decision-making is gaining significance in contemporary times.[64] Intangible assets such as management quality, organizational culture, innovation skills, and brands, which offer enduring financial and social advantages, hold equivalent value over time. Ultimately, a company’s capacity to adjust to a constantly changing economic environment may be more affected by its human, organizational, or intellectual resources rather than environmental, social, and governance indicators.

From a value creation standpoint, variables such as productivity, innovation, brand, and company culture must be considered in addition to ESG concerns, although they are sometimes disregarded. Although ESG is crucial for long-term value, it should not be regarded as a specialised term, as taking into account long-term aspects is essentially sound investment. It is a mistake to treat ESG as a short-term financial investment tool, forgetting the overall competitive strength of the organization.

5.4 ESG as product and ESG as process

Strategic sustainable investing, represented by ESG, offers firms an opportunity. However, it must be a primary emphasis of business model innovation to attain success. Common ESG narratives posits that innovation requires the integration of economic, environmental, and social benefits. Numerous international financial and consulting businesses have converted it into an investment vehicle, leading to a lack of understanding of ESG.

Financial investment firms perceive ESG as a superficial investment product, leading to many challenges and controversies, while ESG should be perceived as a sustainable integrated management process for commercial operations, fundamentally embedded in the entire business operation and molded into sustainable DNA, rather than a fleeting financial investment product.

The quick ascendance of ESG has resulted in misconceptions regarding its definition and the creation of inflated expectations concerning its efficacy and impact.[65] Numerous analysts assert that ESG serves merely as a criterion for assessing the short-term financial performance of assets. The financial sector has converted the processes of defining, analyzing, monitoring, and communicating ESG indicators into a marketable asset, resulting in many investment funds labeling their products as ESG. Business enterprises recognize that their survival depends on balancing the three Ps (People, Planet, Profit). Companies that emphasize the sustainability of their supply chains will exhibit more resilience during market disruptions. Furthermore, enterprises that adeptly manage and curtail wastewater, air pollution, and carbon emissions will incur lower costs for environmental remediation in the forthcoming time.

Although sustainability has been a long-standing aspect of company strategy, ESG investing is a relatively short-term investment. Furthermore, the regular criticisms of ESG investment, such as the reliance on proxies for unobserved data, are as relevant to conventional financial research but are seldom acknowledged as such.[66] The lack of reliable datasets and biased scoring methodologies make the environmental (E) pillar of ESG assessment less meaningful.[67] Nonetheless, integrating ESG principles into company strategies can create long-term value. Organizations can concurrently optimize their financial, social, and environmental performance by implementing risk management strategies, capitalizing on opportunities, meeting stakeholder expectations, and adhering to regulatory requirements. Sustainability must be fully integrated into corporate, business, and product-level strategy, characterized by significant changes such as grassroots leadership, purpose-oriented brand management, and enhanced transparency.[68]

5.5 Contradictory rating

ESG ratings and controversies substantially influence firm performance and valuation, however the consequences differ by area. In Europe and the United States, equities associated with significant ESG concerns generally exhibit inferior performance, whilst those with minimal controversy tend to excel.[69] Sekol, in his book, ESG Mindset: Business Resilience and Sustainable Growth, asserts that a prevalent issue is the excessive emphasis on ESG scores, leading detractors to conflate the ratings with ESG itself.[70] Studies indicate that ESG ratings encounter considerable difficulties regarding equity and dependability. Research indicates significant discord among rating agencies, exhibiting a concerningly low reliability (18.3%) and agreement (5.4%).[71]

Credit ratings that are not ESG scores may vary depending on the rating agency’s definitions and interpretations of ESG, materiality, and stakeholders. Viewing ESG as a compilation of long-term value elements renders many associated disputes inconsequential. The disparity in perceptions regarding the quality of a company’s intangible assets is unsurprising, as demonstrated by the imprecise correlation noted among ESG ratings.[72] More significantly than the confusion caused by the inconsistent methods of rating services, rating organizations should refrain from assigning ratings and charging their clients for services that enhance those rankings.

There is still no consensus on the definition of ESG and the particular domains that ESG investing is expected to address.[73] Although the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is advantageous to various stakeholders and enjoys broad acceptance, ESG standards remain undefined and consequently lack a cohesive regulatory framework, in contrast to the formally constituted and governed auditing sector. Attaining global consensus and uniformity in ESG will necessitate several decades. Recent statistics from Ernst & Young reveal that more than 600 sustainability reporting standards and guidelines are globally available, making sustainability reporting a complex, redundant, and costly endeavor for many organizations.[74] Furthermore, profit-oriented biases in interpreting concepts and theoretical frameworks intensify the confusion and ambiguity around sustainability initiatives, sustainable development, and sustainable business practices.

5.6 Trade-off is common

Environmental ESG practices correlate with enhanced profitability; nonetheless, there are trade-offs among the ESG components.[75]

Although ESG is ostensibly committed to attaining “win-win” results, it constitutes a methodical approach necessitating measuring and analyzing particular environmental, social, and governance elements. Typical scenarios involve either shutting down a polluting industry to preserve environmental integrity or maintaining local employment and implementing extensive layoffs to achieve short-term profit objectives under investor pressure.

In his recent publication, Sustainable Sustainability: Why ESG is not enough, Peshawaria asserts that the “Incentive-Regulation-Remediation-Reward/Punishment” framework, integral to the shareholder-centric paradigm of capitalism and governing ESG, is fundamentally flawed and fosters irresponsible behaviour among corporate management regarding social and environmental issues, despite claims of adherence to sustainable ESG principles. When managers face pressure to deliver a return on investment, it is insufficient to merely reward them for their short-term financial successes quarterly or annually; long-term sustainability objectives require more comprehensive assistance.

Paul Polman, former CEO of Unilever argues that modifying a company’s operational procedures while maintaining its production of goods and services for clients and safeguarding its competitive stance has been compared to replacing an aircraft’s engine mid-flight.[76] Executing a business sustainability transition entails considerable risks that require careful management. These hazards stem from the intricate interrelations of ESG elements in company performance.

A recent KPMG survey indicates that an increasing number of CEOs, currently 45%, feel that ESG programs enhance financial performance, a rise from 37% in 2023.[77] Another study by IBM indicates that expenditure designated for sustainability reporting exceeds that for sustainability innovation by 43 percent.[78] Critics have charged ESG investing firms with fostering baseless optimism, overstating success rates, and hindering the implementation of overdue regulatory measures.[79]

For environmental, social, and governance factors to serve as the principal drivers of long-term value creation, ESG investors require a comprehensive metric to precisely assess and predict long-term value. By providing transparent and comprehensible assessments of the long-term value of ESG investments, corporations may shift the emphasis of financial markets away from short-term profitability.

If environmental, social, and governance factors generate long-term value, they are no more exceptional than any other intangible asset that affects this result. Ironically, policies centered on ESG may not optimally foster green innovation, as demonstrated by the observation that organizations with inferior ESG scores are prominent creators of green patents.[80]

Companies having a higher incidence of ESG disputes are linked to diminished earnings potential, particularly in environmentally sensitive sectors.[81] It is now appropriate to examine a few successful cases that have a strong tie to ESG performance.

5.7 Successful ESG implementations

Contrary to the superficial ESG adoption critiqued, firms like Unilever and Patagonia demonstrate robust integration. Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan aligns economic, environmental, and social goals, reducing emissions by 20% while boosting sustainable brand growth. Similarly, Patagonia’s non-profit ownership model prioritizes environmental impact, countering the profit-driven trade-offs. These cases suggest that embedding ESG into core operations can yield balanced outcomes.

Unilever: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan (USLP), which started in 2010, is a good example of how to integrate ESG into a business strategy. The plan, initiated in 2010, established lofty objectives to dissociate business expansion from environmental repercussions while enhancing favorable social results.[82] Unilever employs scientific evaluation, namely life cycle assessment, as the foundation for its Sustainable Living Plan strategy and programs.[83]

Despite Unilever’s failure to meet all USLP objectives, the firm has expanded by adhering to sustainable principles and has secured a competitive advantage.[84] The USLP made sustainability a part of Unilever’s mission instead of just a cost to avoid. It saw it as a chance to go ahead of the competition, come up with new ideas, and create value for stakeholders.[85] This strategic embedding led to eco-efficient R&D, changes in the supply chain, and brand marketing that focused on sustainability. In the end, this brought in money as well as environmental and social benefits. Unilever’s sustainable-living brands actually grew 46 percent quicker and made up 70 percent of turnover growth. This is a strong example of how thoroughly integrated ESG can solve the profit-sustainability contradiction.[86] Unilever still receives criticism for issues such as plastic pollution and problems with the supply of palm oil, but the USLP case shows how strict, system-wide ESG practices can provide long-term shared benefit.

Patagonia: Patagonia sees ESG as more than just a marketing tool; it sees it as a key part of doing business. The corporation has promised to provide 1% of its yearly sales to environmental causes since the 1980s. This adds purpose to its operations in a structural way (Patagonia 2023–24 B Corp Report).[87] In 2022, Patagonia made more efforts to make its environmental goal permanent by giving 98 percent of its non-voting shares to the Holdfast Collective and 2 percent of its voting shares to the Patagonia Purpose Trust.[88] This governance model legally preserves Patagonia’s commitment on sustainability by making sure that profits go to environmental activities instead of private benefit. Patagonia’s sustainable marketing strategy has facilitated its success while upholding environmental and social responsibility, especially amid the COVID-19 pandemic.[89] The firm shows how ESG can be “process,” not just product, through things like Worn Wear and supply-chain transparency.

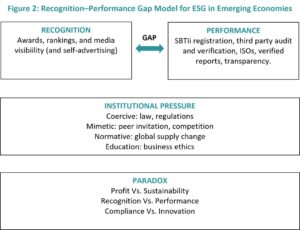

6. Analytical Framework: Explaining the Recognition–Performance Gap in ESG

Descriptive data indicate that Vietnamese enterprises prefer recognition (awards, rankings, public remarks) over performance (validated ESG promises, SBTi registration, third-party audits); nonetheless, a more profound study necessitates a theoretical framework. Paradox theory and institutional theory elucidate the reasons for the persistence of this gap and its implications for rising economies.

6.1. Paradox Theory: Navigating Contradictory Demands

Smith and Lewis contend that the paradox theory posits that organizations frequently encounter enduring and interrelated tensions that cannot be resolved but must be managed.[90] Although paradoxes can cause tensions and disputes, they can also be handled defensively, which leads to dysfunction, or they can be seen as chances for proactive management, which promotes innovation and competitive advantage.[91] ESG frameworks encompass numerous paradoxes:

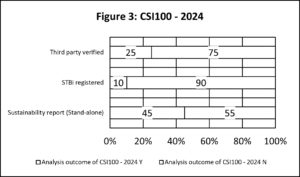

- Profit vs. Sustainability: Firms in Vietnam face short-term market and shareholder pressures while being called upon to make long-term sustainability investments. The lack of verified commitments (only 25% of CSI100 firms with assurance reports) reflects a prioritization of immediate financial survival over costly environmental transformation.

- Recognition vs. Verification: Awards like CSI100 and CSA50 promote symbolic engagement. Recognition provides reputational capital at minimal expense, whereas verification via SBTi or third-party audits requires substantial resources.

- Compliance vs. Innovation: ESG is sometimes characterized as adherence to reporting criteria. Transformative ESG necessitates innovation in business models. Vietnamese companies continue to get ensnared in compliance-oriented reporting, eschewing the more perilous route of innovation.

These contradictions are not exclusive to Vietnam; nonetheless, they are exacerbated in environments characterized by inadequate regulatory enforcement and little resources for sustainable innovation.

6.2 Institutional Theory: Symbolic vs. Substantive Adoption

Institutional theory highlights the manner in which organizations implement methods to attain legitimacy within their institutional context.[92] ESG practices in Vietnam exemplify institutional isomorphism, as companies replicate worldwide ESG narratives to align with the expectations of regulators, investors, and the public. Nonetheless, adoption primarily remains symbolic rather than substantive.[93]

- Coercive pressures, such as laws and decrees, are ineffectively applied in Vietnam; Decree 08/2022/ND-CP offers instructions but is devoid of rigorous punishments. This diminishes motivations for authentic adherence.

- Mimetic pressures compel corporations to adopt sustainability rhetoric without integrating it into their strategy. For instance, 46% of Vietnamese companies reference ESG in the KPMG study, while less than 10% provide independent assurance disclosures, mentioned in one PwC’s 2024 report.

- Normative demands from professional associations and global supply chains are inconsistent: foreign direct investment firms linked to international networks implement more stringent standards (e.g., Unilever Vietnam), whereas domestic small and medium-sized enterprises emphasize cost efficiency.

Consequently, ESG in Vietnam functions primarily as a legitimacy-seeking endeavor rather than a performance-driven strategy.[94] This also occurs in India. Despite the establishment of mandated CSR expenditure and ESG reporting guidelines, practical execution frequently fails because to ambiguous disclosures, greenwashing, and a compliance-oriented mentality [95], while leading Thai corporations emphasize thorough ESG disclosure, environmental initiatives, employee welfare, governance, and community development in their messaging.[96] The “recognition over performance” conundrum arises as symbolic ESG provides reputational legitimacy at a lower cost than actual ESG.

6.3. Toward a Conceptual Model: The Recognition–Performance Gap

Integrating these perspectives, we propose the Recognition–Performance Gap Model for ESG in Emerging Economies:

- External recognition (awards, media, rankings) provides quick legitimacy and satisfies stakeholders.

- Verification mechanisms (SBTi, third-party audits) are costly and weakly enforced, so adoption remains low.

- Result: A widening gap between ESG discourse and ESG performance.

This model explains why ESG in Vietnam appears vibrant in public communication but underdeveloped in practice (Figure 2

- Implications

- Theory: The Vietnam case exemplifies how ESG paradoxes are influenced by weak institutions, hence expanding paradox theory within the realm of sustainability research in emerging markets.

- Policy: Enhancing coercive procedures (compulsory third-party audits) and establishing incentives for meaningful adoption are crucial to bridging the recognition-performance gap.

- Practice: Firms must shift from symbolic legitimacy-seeking to integrated ESG strategies that deliver long-term resilience and competitiveness.

The mere 25% of CSI2024 enterprises with verified reports highlights an institutional deficiency: in the absence of robust regulatory enforcement, firms pursue symbolic acknowledgment instead of genuine compliance.

This corresponds with instINSERTitutional theory’s observation that companies in poorly regulated settings implement ceremonial ESG measures to preserve legitimacy, rather than achieving authentic integration.

7. Recognition mismatches reality:

7.1 Case analysis of TOP 100 CSI2024, Vietnam

Building on the historical origins of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles, Section 5 will analyze the practical barriers to their adoption in emerging economies, with a specific focus on Vietnam.

A primary challenge is the voluntary nature of most ESG initiatives. This can prevent organizations from moving beyond a mere compliance mindset to achieve genuine, systemic change. This is especially true when ESG is perceived as a distraction from a company’s core mission rather than a strategic framework to enhance it.

The sustainability reports (aka ESG report) from the 100 firms awarded the CSI100 sustainability accolade in 2024 reveal that the outcomes closely align with those identified in the overview analysis. Excluding FDI firms registered with SBTi, 100% of domestic enterprises are unregistered with this body, constituting 90% of the total 100 enterprises examined (Figure32).

This outcome parallels the PwC study referenced in section 3.4, indicating that the implementation by domestic firms is weak relative to the grandiose claims made in the media. Of the 100 companies studied, 45% had independent sustainability reports.

This indicates that numerous enterprises are merely employing it as a coping strategy while. Vietnamese legislation does not mandate listed companies to produce independent sustainability reports or undergo third party verification, except in specific sectors requiring obligatory emissions reporting, such as energy, construction, and logistics.

Concerning sustainability reports verified and audited by an external entity, only 25% of the 100 sampled firms had documented limited assurance verification, encompassing foreign direct investment and domestic enterprises (Figure 2). This is due to the high cost of audits, limited expertise in sustainability reporting and probably weak enforcement of Vietnam’s Decree 08/2022/ND-CP. While the research findings may not adequately represent all domestic firms, they illustrate the disparity between sustainable claims and actual practices. This study’s limitation lies in the insufficient foundation to validate the effects of the sustainability programs implemented by the 100 enterprises examined; it merely investigates the degree of adherence to sustainability reporting beyond the voluntary scope of the enterprises.

7.2 Case analysis of TOP50 CSA2024, Vietnam

Organized by Nhip Cau Dau Tu magazine, the 2025 TOP50 CSA chapter is the third straight year of recognizing 50 sustainable enterprises in Vietnam. This prize, bolstered by the magazine’s endorsement, has emerged as one of the most esteemed accolades.

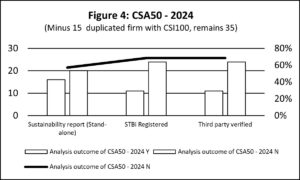

However, out of the 35 firms examined, after excluding 15 that coincided with the CSI100 award list, no domestic enterprises registered with SBTi for net-zero emission reduction targets. Of the 35 firms, 11 multinational organizations have registered with SBTi through the parent company’s plan, including Unilever, DKSH, and Panasonic, representing 31% (Figure 3). In the remaining instances, where the criterion of possessing an stand-alone sustainability report applies, constituting 57%, the report was not validated by an independent third party, representing 69% (CSI100 75%). The proportion of enterprises with stand-alone sustainability reports not certified by a third party is quite similar in two group (45% and 46%).

This study exhibits two differences: a smaller sample size of 35 and a greater share of multinational firms relative to the CSI2024 list, resulting in 31% of organizations registered with SBTi, compared to 25% for the CSA2024 list. Nonetheless, the limited sample size renders the statistical findings only suggestive.

The aggregated findings from the analysis of CSI100 and TOP50 CSA indicate that merely 16% of companies are registered with SBTi, whereas 45% of the 135 examined firms produce independent sustainability reports. Nevertheless, the 16% of corporations are global enterprises, and no Vietnamese firms have registered with SBTi to date. FDI firms’ higher compliance rates demonstrate normative isomorphism via supply chains.

| Results Table: ESG Indicators in CSI2024 & CSA2024 Samples | |||

| Indicators | CSI2024 (TOP 100) | CSA2024 (TOP 50) | Combined Samples |

| Total firm review | 100 | 35 | 135 |

| Stand-alone Sustainability Report (% | 45% | 46% | 45% |

| Third-Party Assurance (%) | 25% | 31% | 27% |

| SBTi registered (%) | 10% | 31% | 16% |

In addition to internal obstacles such as capacity, budget and non-mandatory national policies, one of the most challenging obstacles is the requirements of absolute contraction approach’s baseline year requirements from SBTi, as stated in the latest IBM Corporate Sustainability Report 2024-25, page 37: “Although our net-zero targets align with, or are more ambitious than, this science-based reduction pathway, we face challenges in gaining formal approval for a near-term emissions-reduction target under the methodology of the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) due to the absolute contraction approach’s baseline year requirements.” Despite possessing the means and intention, IBM has not yet established a net-zero targets approved by SBTi .

Note: Stand-alone reports are mostly from FDI companies and none of the organizations registered with the SBTi are Vietnamese enterprises.

8. Discussion: Synthesizing ESG Paradoxes and SDG Alignment

This study elucidates the paradoxes of ESG, comprising the contradiction between short-term profits and long-term sustainability (section 5.2), contradictory ratings (section 5.5), and the risks of greenwashing (section 4). These are the same as the problems with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Putting profit first goes against SDG 8’s goal of sustainable economic growth.

At the same time, unreliable ratings get in the way of SDG 12’s focus on responsible production. Unilever and Patagonia are two successful companies that show how adding ESG to strategy can help solve these problems. This can support SDG 13 (Climate Action) by showing reduced carbon emissions. Weak sustainability report and implementation in Vietnam highlights the need for improved partnerships and regulatory enforcement as specified in SDG 17 (e.g., Decree 08/2022/ND CP). Standardizing global ESG criteria, as proposed, may advance SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) by fostering open governance.

While the research findings may not adequately represent all domestic firms, they illustrate the disparity between sustainable claims and actual practices. This study’s limitation lies in the insufficient foundation to validate the effects of the sustainability programs implemented by 135 enterprises examined; it merely investigates the degree of adherence to sustainability reporting beyond the voluntary scope of the enterprises.

Globally, setting and reaching net-zero goals presents substantial hurdles, according to recent study. In order to offer net-zero emissions buildings, organizations must overcome technological, knowledge, and financial obstacles.[97] Accounting problems pertaining to timing, target boundaries, techniques, and monitoring mechanisms impede the conversion of global decarbonization goals into organizational targets.[98]

Although net-zero targets are prevalent, only a limited number satisfy fundamental criteria for rigor, underscoring the difficulties in establishing successful net-zero objectives.[99] In addition to internal challenges such as human resource capacity, budget, and non-mandatory national policies in Vietnam, a significant obstacle is the absolute contraction approach’s baseline year requirements mandated by SBTi.

9. Recommendation

The voluntary nature of ESG activities differs from obligation. When ESG becomes a distraction from the core purpose of a sustainability-oriented company, it may revert to prioritizing shareholder interests. Considering the substantial influence of corporate purchasing power, whether via stocks or commodities, ESG may divert attention from the most pressing global issues. The ESG framework may mislead stakeholders into believing that the economy and businesses are advancing.

Sustainability / ESG reporting should be legally mandated to mitigate greenwashing, deter socially unsustainable investments, and promote the Sustainable Development Goals. Numerous authorities have intervened and enacted rules and regulations about ESG disclosure and transparency. The European Union’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive mandates that large firms provide comprehensive reports regarding their operations’ governance, social, and environmental effects. The government and regulators are crucial in enabling systemic reform, whereas the markets can only exert an impact.

While the ESG framework is praiseworthy, the ratings, guidelines, and standards encounter difficulties in attaining requisite accuracy and specificity, leading to greenwashing and superficial compliance, especially concerning the “E” and “S.”

Moreover, much ambiguity fosters inequity and injustice in the evaluation outcomes among companies. Therefore, to ensure greater equity and consistency in the assessment and distribution of sustainability, it is essential to share corporate sustainability scoring methodologies and criteria and advance towards global regulatory and legislative harmonization, akin to the accomplishments of the auditing and accounting industries.

Furthermore, the “G” component must not be overlooked. Governance in financial and investment contexts concerns the interactions and relationships among shareholders, investors, and board members. Multiple stakeholders, such as customers, authorities, and partners, are reluctant to be governed. Customers and local communities require proactive engagement initiatives, whilst employees necessitate effective management. Consequently, governance holds no significance for stakeholders other than the members of the board of directors. The proposal advocates for the adaptation and expansion of ESG to meet practical needs.

The article brings together prior criticisms (such as those of Edmans and Peshawaria), yet it can stand out by focusing on Vietnam-Specific Paradoxes: Section 6’s emphasis on superficial ESG adoption in Vietnam is distinctive yet insufficiently developed. For example, the examination of CSI100 and TOP50 CSA shows that 16% of companies are registered with SBTi and 45% publish independent sustainability reports. However, 16% of corporations are global, and no Vietnamese firms have registered with SBTi. For Vietnam, it would be a good idea to make Decree 08/2022/ND-CP stronger by requiring third-party audits and incentivizing companies to comply with SBTi. For instance, to amend Decree 08/2022/ND-CP to require third-party assurance for CSI2024 enterprises could help Vietnam fight greenwashing and meet SBTi’s science-based aims.

10. Conclusion, Contribution and Limitations

10.1 Conclusion

This study has demonstrated that ESG, despite its rapid proliferation throughout industry, politics, and civil society globally, is ensnared in contradictions that diminish its potential to effect change. ESG engenders conflicts in both its methodology and its outcomes. For instance, it engenders a tension between immediate profit and long-term sustainability objectives, between inconsistent evaluations and the necessity for transparency, and between compliance-driven protocols and the innovative transformation required for sustainability. These paradoxes frequently manifest as greenwashing and superficial acceptance, particularly in emerging economies.

The Vietnam’s cases (TOP100 CSI2024 and TOP50 CSA2024) distinctly illustrate this paradox: while firms vigorously pursue acknowledgment via sustainability awards, a limited number attain rigorous international benchmarks such as SBTi registration or third-party certification. This divergence between symbolic advancement and actual performance underscores the intrinsic vulnerability of voluntary ESG frameworks in contexts marked by insufficient regulatory enforcement and resource constraints.

Nonetheless, ESG when practice it rightly possesses certain potential. Unilever and Patagonia are two global enterprises demonstrate how businesses may harmonize profitability with sustainability by integrating ESG as a fundamental management process that connects with brand strategy, supply chain integrity, and governance. In this manner, they can generate enduring value for all stakeholders. Vietnam and other growing nations must undertake three interconnected actions: harmonizing rules with global disclosure standards, mandating third-party verification to eliminate greenwashing, and transitioning from shareholder-centric governance to a stakeholder-inclusive approach.

For ESG to serve as a catalyst for innovation, resilience, and tangible advancement towards the Sustainable Development Goals, enterprises must transcend mere compliance and integrate sustainability into their core values. In the absence of this transformation, ESG risks becoming become a superficial endeavor that attracts attention without effecting any substantive change.

10.2. Contributions to theory and practice

This study advances both theoretical understanding and practical application of ESG practices in emerging economies.

Theoretical Contributions

The study advances paradox theory by developing the Recognition–Performance Gap Model. Although paradox theory has historically highlighted the enduring nature of conflicting organizational needs (Smith and Lewis 2011), our results indicate that in frail institutional contexts, contradictions do not just endure but are structurally distorted. Recognition (awards, rankings, media awareness) supersedes performance (verification, third-party audits, science-based pledges) as the primary means of organizational reaction. This broadens paradox theory by demonstrating that inadequate enforcement and resource limitations lead to symbolic prioritization as a coping strategy, rather than equitable paradox management.

Secondly, the research enhances institutional theory by demonstrating how the symbolic acceptance of ESG practices in Vietnam embodies a unique amalgamation of coercive, mimetic, and normative influences. In contrast to companies in developed economies, where coercive and normative mechanisms bolster substantial ESG integration, Vietnamese firms function in an environment characterized by weak coercive regulation, mimetic pressures prioritizing rhetoric over substance, and inconsistent normative pressures from supply chains. Our Recognition–Performance Gap Model advances institutional theory by illustrating how legitimacy-seeking in emerging economies creates a systemic disparity between rhetoric and actual performance.

Third, by integrating paradox theory with institutional theory, the study provides a conceptual synthesis that connects global ESG contradictions to local institutional contexts. This integration offers a transferable paradigm for examining ESG adoption in other emerging economies with comparable institutional deficiencies, including Indonesia, the Philippines, and India.

Practical Contributions

The model underscores the dangers of overdependence on recognition-oriented ESG policies for managers. Awards and rankings confer reputational capital, render corporations susceptible to allegations of greenwashing, and establish enduring weaknesses within global supply chains. Companies must shift from superficial ESG implementation to meaningful practices by investing in credible promises and independent audits.

The study emphasizes to policymakers the necessity of enhancing coercive mechanisms, including the mandatory provision of sustainability reports, adherence to international frameworks (e.g., ISSB, EU CSRD), and incorporation of trade-related measures such as the EU CBAM. Without these measures, the recognition-performance disparity will continue, jeopardizing Vietnam’s competitiveness within global value chains.

The approach necessitates reassessing award and ranking systems for business associations, including TOP100 CSI2024 and TOP50 CSA2024. By correlating recognition with validated performance metrics, organizations can convert symbolic incentives into meaningful catalysts for sustainability.

Collectively, these contributions illustrate that the recognition–performance gap is not a peripheral issue but a fundamental characteristic of ESG adoption in emerging economies. The Recognition–Performance Gap Model provides a novel theoretical framework and practical strategy for bridging this disparity.

10.3 Limitation and future research

This study has some limitations that also present opportunities for further investigation. The analysis mainly examines Vietnamese business sustainability reports and award programs.

The conclusions would be enhanced by integrating primary data through interviews with managers, auditors, and regulators, or by employing systematic content analysis on a broader dataset of reports, in conjunction with triangulation from secondary sources. The report is specific to Vietnam, serving as a case study of ESG paradoxes in emerging countries.

While the Recognition–Performance Gap Model possesses translational potential, subsequent research should evaluate and enhance the framework within other institutional contexts, especially in ASEAN economies like Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines.

Additionally, the study emphasizes paradox and institutional theory as interpretive lenses; additional perspectives, such as stakeholder theory or legitimacy theory, may further enrich the understanding of why firms prioritize recognition over performance.

Subsequent comparative and longitudinal research would be beneficial in investigating whether the recognition–performance gap diminishes as regulatory frameworks evolve and global supply chain demands escalate.

This study merely reports a segment of the reality about sustainable business transformation practices in Vietnam and does not validate the ethical standards of the businesses, nor does it illustrate the effects of the impact of sustainable initiative measures undertaken by the organizations examined.

11. Conflict of interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

12. Acknowledgment

I want to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Kabiru Gulma and Professor Momodou Mustapha Fanneh for their enthusiastic guidance in the ACA-401D and SD-200 courses, which have strengthened my academic writing skills and fundamental knowledge of sustainable development.

References

Aldowaish, Alaa, Jiro Kokuryo, Othman Almazyad, and Hoe Chin Goi. ‘Environmental, Social, and Governance Integration into the Business Model: Literature Review and Research Agenda’. Sustainability 14, no. 5 (2022): 2959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14052959.

Anna, Kofi. ‘Kofi Annan’s Address to World Economic Forum in Davos | United Nations Secretary-General’. Accessed 10 September 2024. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/1999-02-01/kofi-annans-address-world-economic-forum-davos.

ARE, Federal Office for Spatial Development. ‘1987: Brundtland Report’. Accessed 20 July 2024. https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/medien-und-publikationen/publikationen/nachhaltige-entwicklung/brundtland-report.html.

Arvidsson, Susanne, and John Dumay. ‘Corporate ESG Reporting Quantity, Quality and Performance: Where to Now for Environmental Policy and Practice?’ Business Strategy and the Environment 31, no. 3 (2022): 1091–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2937.

Auerbach, Carl, and Louise B. Silverstein. Qualitative Data: An Introduction to Coding and Analysis. NYU Press, 2003.

Aydoğmuş, Mahmut, Güzhan Gülay, and Korkmaz Ergun. ‘Impact of ESG Performance on Firm Value and Profitability’. Borsa Istanbul Review, Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) and Sustainable Finance, vol. 22 (December 2022): S119–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2022.11.006.

Barko, Tamas, Martijn Cremers, and Luc Renneboog. ‘Shareholder Engagement on Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance’. Journal of Business Ethics 180, no. 2 (2022): 777–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04850-z.

Becker, H.S. Field Work Evidence. In H. Becker, Sociological Work: Method and Substance (Pp. 39-62). Transaction Books, 1970.

Bonaparte, Isaac. ‘Environmental, Social, and Governance Controversies and Earnings Quality’. Corporate Ownership and Control 21, no. 4 (2024): 89.

Bowen, Glenn A. ‘Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method’. Qualitative Research Journal 9, no. 2 (2009): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027.

Carrión, Elena, Carlos Larrinaga, and Deborah Rigling Gallagher. ‘Carbon Accounting for the Translation of Net-Zero Targets into Business Operations’. The British Accounting Review 57, no. 2 (2025): 101456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2024.101456.

Carroll, Archie B. ‘Carroll’s Pyramid of CSR: Taking Another Look’. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 1, no. 1 (2016): 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6.

Center for Responsible Business. ‘Peter Drucker on the Purpose of Business’. Berkeley Haas. Accessed 11 September 2024. https://haas.berkeley.edu/responsible-business/blog/posts/peter-drucker-on-the-purpose-of-business/.

Chandra, Dakshina, and Navajyoti Samanta. ‘Between Compliance and Commitment: Evaluating India’s ESG Regulatory Framework’. Amicus Curiae 6, no. 3 (2025): 743–72. https://doi.org/10.14296/ac.v6i3.5795.

Charlin, Ventura, Arturo Cifuentes, and Jorge Alfaro. ‘ESG Ratings: An Industry in Need of a Major Overhaul’. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 14, no. 4 (2024): 1037–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2022.2113358.

Christensen, Hans B., Luzi Hail, and Christian Leuz. ‘Mandatory CSR and Sustainability Reporting: Economic Analysis and Literature Review’. Review of Accounting Studies 26, no. 3 (2021): 1176–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09609-5.

Club of Rome. ‘The Limits to Growth’. Accessed 2 September 2024. https://www.clubofrome.org/publication/the-limits-to-growth/.

Cohen, Lauren, Umit G. Gurun, and Quoc Nguyen. ‘The ESG – Innovation Disconnect: Evidence from Green Patenting’. SSRN Electronic Journal, ahead of print, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3718682.

Cybellium. Mastering ESG: A Comprehensive Guide To Become An ESG Expert. Independently published, 2023.

Delgado-Ceballos, Javier, Natalia Ortiz-De-Mandojana, Raquel Antolín-López, and Ivan Montiel. ‘Connecting the Sustainable Development Goals to Firm-Level Sustainability and ESG Factors: The Need for Double Materiality’. BRQ Business Research Quarterly 26, no. 1 (2023): 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/23409444221140919.

Derqui, Belén. ‘Towards Sustainable Development: Evolution of Corporate Sustainability in Multinational Firms’. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 27, no. 6 (2020): 2712–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1995.

Dzieliński, Michał, Florian Eugster, Emma Sjöström, and Alexander F. Wagner. ‘Do Firms Walk the Climate Talk? *’. SSRN Scholarly Paper 4021061. Social Science Research Network, 31 May 2024. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4021061.

Edmans, Alex. ‘Rational Sustainability’. SSRN Scholarly Paper 4701143. Rochester, NY, 20 January 2024. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4701143.

Edmans, Alex. ‘The End of ESG’. Financial Management 52, no. 1 (2023): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12413.

EY, and Oxford Analytica. ‘The Future of Sustainability Reporting Standards’. EYGM, 2021.

Fan, Yi, and Yang Gao. ‘ESG or Profitability? What ESG Mutual Funds Really Care About Most’. SSRN Scholarly Paper 4257959. Social Science Research Network, 31 May 2022. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4257959.

Franco, Carmine de. ‘ESG Controversies and Their Impact on Performance’. The Journal of Investing 29, no. 2 (2020): 33–45. https://doi.org/10.3905/joi.2019.1.106.

‘Global-Survey-of-Sustainability-Reporting-2022.Pdf’. n.d. Accessed 30 September 2024. https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/se/pdf/komm/2022/Global-Survey-of-Sustainability-Reporting-2022.pdf.

GRI. ‘GRI – Standards’. Accessed 16 August 2025. https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/.

Hahn, Rüdiger. Sustainability Management: Global Perspectives on Concepts, Instruments, and Stakeholders. Rüdiger Hahn, 2022.

Hale, Thomas, Stephen M. Smith, Richard Black, et al. ‘Assessing the Rapidly-Emerging Landscape of Net Zero Targets’. Climate Policy 22, no. 1 (2022): 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2021.2013155.

Hannah, David R., and Brenda A. Lautsch. ‘Counting in Qualitative Research: Why to Conduct It, When to Avoid It, and When to Closet It’. Journal of Management Inquiry 20, no. 1 (2011): 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492610375988.

Hanson, Dan. ‘ESG Investing in Graham & Doddsville’. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 25, no. 3 (2013): 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12024.

Härtel, Charmine E. J., and Anna Krzeminska. ‘Paradox Theory’. In A Guide to Key Theories for Human Resource Management Research. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781035308767.ch22.

Hawk, Thomas F. ‘An Ethic of Care: A Relational Ethic for the Relational Characteristics of Organizations’. Edited by Maurice Hamington and Maureen Sander-Staudt. Vol. 34. Issues in Business Ethics. Springer Netherlands, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9307-3_1.

Helfaya, Akrum, and Phuong Bui. ‘Exploring the Status Quo of Adopting the 17 UN SDGs in a Developing Country—Evidence from Vietnam’. Sustainability 14, no. 22 (2022): 15358. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215358.

Hien, Tran Thi, and Thu Huong Tran. ‘Sustainability Reporting in Vietnam: Evolutionary or Revolutionary? A Case Study of Five Public Companies’. Journal of International Economics and Management 21, no. 2 (2021): 128–48. https://doi.org/10.38203/jiem.021.2.0032.

Huang, Chih-Hung, Duy The Phan, and Chung-Sung Tan. ‘CO2 Utilization’. Edited by James A. Kent, Tilak V. Bommaraju, and Scott D. Barnicki. Springer International Publishing, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52287-6_33.

IBM. ‘Corporate Social Responsibility Report 2024-25’. Intel. Accessed 17 August 2025. https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/corporate-responsibility/corporate-responsibility.html.

IBM. ‘IBM Study: Sustainability Remains a Business Imperative, But Current Approaches Are Falling Short’. IBM Newsroom. Accessed 10 September 2024. https://newsroom.ibm.com/2024-02-28-IBM-Study-Sustainability-Remains-a-Business-Imperative,-But-Current-Approaches-are-Falling-Short.

IMF. ‘Greenhouse Emissions Rise to Record, Erasing Drop During Pandemic’. 30 June 2022. https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2022/06/30/greenhouse-emissions-rise-to-record-erasing-drop-during-pandemic.

Khan, Mozaffar. ‘ESG Misconceptions: Putting Problems in Perspective Can Lead to Better Solutions’. The Journal of Impact and ESG Investing 4, no. 1 (2023): 82–86. https://doi.org/10.3905/jesg.2023.1.077.

King, Andrew, and Pucker Kenneth. ‘ESG and Alpha: Sales or Substance?’ Institutional Investor, 25 February 2022. https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/2bstmmn7nssoo5njqf5kw/opinion/esg-and-alpha-sales-or-substance.

KPMG. ‘The Move to Mandatory Reporting – KPMG Vietnam’. KPMG, 29 November 2024. https://kpmg.com/vn/en/home/insights/2024/11/the-move-to-mandatory-reporting.html.

Larcker, David F., Brian Tayan, and Edward M. Watts. ‘Seven Myths of ESG’. European Financial Management 28, no. 4 (2022): 869–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/eufm.12378.

Latapí Agudelo, Mauricio Andrés, Lára Jóhannsdóttir, and Brynhildur Davídsdóttir. ‘A Literature Review of the History and Evolution of Corporate Social Responsibility’. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility 4, no. 1 (2019): 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-018-0039-y.

Lawrence, Joanne, Andreas Rasche, and Kevina Kenny. ‘Sustainability as Opportunity: Unilever’s Sustainable Living Plan’. In Managing Sustainable Business: An Executive Education Case and Textbook. Springer Science+Business Media, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_21.

Leelawati, Ashu, Leena, Jasdeep, and Aakansha Singh. ‘Unilever’s Ethical Decision-Making In CSR And Sustainable Business Practices’. International Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2 June 2025, 1427–41. https://doi.org/10.64252/qtk0xs69.

Lu, Ray. ‘Set It in Stone: Patagonia and the Evolution toward Stakeholder Governance in Social Enterprise Business Structures’. SSRN Scholarly Paper 5179548. Social Science Research Network, 14 August 2024. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5179548.

Mahmoodi, Masoud, Eziaku Rasheed, and An Le. ‘Systematic Review on the Barriers and Challenges of Organisations in Delivering New Net Zero Emissions Buildings’. Buildings 14, no. 6 (2024): 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14061829.

Mahoney, Lois S. ‘Standalone CSR Reports: A Canadian Analysis’. Issues In Social And Environmental Accounting 6, no. 1 (2012): 4. https://doi.org/10.22164/isea.v6i1.62.

Marrewijk, Marcel van. ‘Concepts and Definitions of CSR and Corporate Sustainability: Between Agency and Communion’. Journal of Business Ethics 44, no. 2 (2003): 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023331212247.

Maximilian, Angerer, Mwanza Ray, Miller Sydney, R. Pulikanti Sridhar, Suzuki Risa, and W. Robertson Robert. ‘Sustainability Marketing as a Success Factor – The Path of Patagonia before and after Covid-19’. I-Manager’s Journal on Management 17, no. 2 (2022): 40. https://doi.org/10.26634/jmgt.17.2.18996.

Maxwell, Joseph A. ‘Using Numbers in Qualitative Research’. Qualitative Inquiry 16, no. 6 (2010): 475–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410364740.

McLachlan, Stuart, and Dean Sanders. The Adventure of Sustainable Performance: Beyond ESG Compliance to Leadership in the New Era. 1st edition. Wiley, 2023.

Meyer, John W., and Brian Rowan. ‘Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony’. American Journal of Sociology 83, no. 2 (1977): 340–63. https://doi.org/10.1086/226550.

MITSloan. ‘Social Responsibility Matters to Business – A Different View from Milton Friedman from 50 Years Ago | MIT Sloan’. 30 June 2021. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/experts/social-responsibility-matters-to-business-a-different-view-milton-friedman-50-years-ago.