ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

| Cervical cancer disproportionately affects women in low- and middle-income countries, including Ethiopia, where it remains a major public health concern. Late-stage diagnoses are prevalent, often due to systemic, sociocultural, and individual barriers. Early detection is critical, yet most cervical cancer patients in Addis Ababa seek care at advanced stages. This study assessed patient profiles, barriers, and treatment pathways to inform evidence-based interventions for early detection and equitable care.

A mixed-methods approach was employed, collecting quantitative data from 386 newly diagnosed patients at referral hospitals in Addis Ababa (September–December 2024) and qualitative insights from in-depth interviews with patients, healthcare providers, and program managers. Thematic analysis complemented statistical findings. Results showed that 31.1% of patients presented with late-stage cervical cancer. Regular Pap smear screening and frequent healthcare visits were strong predictors of early diagnosis. Notably, HIV/AIDS history correlated with lower late-stage diagnoses, highlighting the role of integrated HIV and cervical cancer care. Key barriers included low awareness, financial constraints, geographic inaccessibility, misconceptions, and stigma. Socioeconomic and geographic disparities were evident, with uneducated and rural patients disproportionately affected. The study underscores the need for enhanced community awareness, decentralized healthcare services, and expanded insurance coverage for screening and treatment. Strengthening stakeholder collaboration, integrating cervical cancer screening with maternal health and HIV care, and launching culturally tailored education campaigns are essential to reducing late-stage diagnoses and improving outcomes in Ethiopia and low-resource settings. |

1. Introduction

Cervical cancer remains a major public health concern worldwide, ranking as the fourth most common cancer among women. In 2022 alone, approximately 660,000 new cases and 350,000 deaths were reported globally, with low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) bearing a disproportionate burden due to inadequate prevention, screening, and treatment services.[1] Sub-Saharan Africa, including Ethiopia, faces significant challenges in combating cervical cancer due to structural, economic, and healthcare system barriers.[2]

Ethiopia, with an age-standardized cervical cancer incidence rate of 21.5 per 100,000 women, exceeds the global average of 13.3.[3] Late-stage diagnosis remains a major issue, with six in ten cervical cancer cases detected at advanced stages, resulting in poor survival outcomes. Despite national guidelines prioritizing early screening and treatment, most patients in Addis Ababa are diagnosed late.[4] This underscores the need to examine the factors influencing the timing of cervical cancer diagnosis.

This study seeks to explore key factors that determine whether cervical cancer is diagnosed at an early or late stage in Addis Ababa’s public health facilities. The central research questions include understanding the demographic, clinical, and systemic factors that influence early or late diagnosis, identifying barriers and enablers affecting the uptake of cervical cancer prevention services, and examining stakeholder roles in timely diagnosis and treatment-seeking behavior. The study’s objectives are to analyze demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics associated with cervical cancer diagnosis timing, assess systemic and behavioral barriers affecting early detection, examine the roles of key stakeholders in cervical cancer prevention, and inform evidence-based interventions aimed at reducing late-stage diagnoses.

This mixed-methods research integrates quantitative patient data with qualitative insights from key informants, providing a holistic understanding of cervical cancer diagnosis patterns in Addis Ababa. The findings contribute to improving early detection strategies and reinforcing global cervical cancer elimination efforts.

2. Determinants of Cervical Cancer Diagnosis and Prevention

This section examines the burden of cervical cancer, factors influencing timely diagnosis, prevention, and global strategies for elimination. Understanding these determinants is critical for designing effective interventions and aligning Ethiopia’s efforts with global elimination goals.

2.1. Cervical Cancer and Its Burden

Cervical cancer is primarily caused by persistent infection with high-risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV-16 and HPV-18. The disease disproportionately affects LMICs due to limited screening and HPV vaccination programs. In Ethiopia, where access to preventive services remains suboptimal, cervical cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths among women. The burden is exacerbated by social determinants of health, including limited awareness, cultural stigma, and economic constraints. According to the Addis Ababa Cancer Registry, cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women, accounting for 14.5% of all cancer cases.[5]

Multiple barriers contribute to late-stage cervical cancer diagnosis. Limited awareness and health literacy prevent many women from seeking timely screening and treatment.[6] Screening rates remain low due to cultural stigma, high costs, and inadequate infrastructure, with default rates reaching 60-80%.[7] Vaccine hesitancy, school-based delivery limitations, and parental consent requirements hinder HPV vaccination.[8] Treatment challenges include unclear referral pathways, specialist shortages, high costs, and long wait times, with only 24.5% receiving adequate radiotherapy in Ethiopia.[9] Furthermore, unreliable cancer registry data, low political commitment, and financial constraints further exacerbate the situation.[10],[11]

2.2. Enablers and Stakeholder Roles in Prevention

Despite challenges, several factors facilitate cervical cancer prevention in Ethiopia. The Ethiopian Ministry of Health has prioritized cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination as key interventions in the National Cancer Control Plan. The national HPV vaccination program, introduced in 2018, has achieved an administrative coverage of 96.2% among adolescent girls in school-based settings.[12] Healthcare providers, including trained nurses and community health extension workers (HEWs), play a vital role in raising awareness, promoting screening, and administering vaccines. Close to a third (27%) of cervical cancer screenings were referred by health posts where HEWs are responsible for these activities.[13] However, gaps remain in reaching out-of-school girls and women in rural areas, where access to preventive services is still limited. A multi-stakeholder approach is essential for cervical cancer prevention.[14]

Government and policymakers are responsible for allocating funding, setting up effective screening programs, and enforcing necessary policies. Through ongoing training, healthcare providers play a critical role in improving diagnostic capabilities and patient education. Community and religious leaders are instrumental in promoting awareness and addressing the stigma associated with health issues.[15] Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international bodies support infrastructure development, resource mobilization, and advocacy efforts.

2.3. Integrated Cervical Cancer Elimination

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a global strategy for cervical cancer elimination, emphasizing a “90-70-90” approach, which aims to achieve 90% HPV vaccination coverage, 70% screening uptake, and 90% treatment of precancerous lesions and invasive cases by 2030.[16] Ethiopia’s elimination efforts require an integrated approach that strengthens community-based screening programs, expands HPV vaccination beyond school-based initiatives, and decentralizes treatment services to improve accessibility. Women living with HIV are six times more likely to develop cervical cancer compared to those without HIV.[17] Integrating cervical cancer prevention with other health programs, such as HIV/AIDS care and maternal health services, can enhance service delivery efficiency and increase uptake.[18]

2.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Health-Seeking Behavior

Two key theoretical models underpin this study. The Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) highlights the influence of individual, interpersonal, community, and systemic factors on health-seeking behaviors.[19] It is particularly relevant in understanding barriers at multiple levels, from individual awareness to structural healthcare challenges. The Delayed Behavior Model (DBM) categorizes delays in diagnosis into patient-related, healthcare provider-related, and systemic factors.[20] Understanding these delays can inform targeted interventions to reduce late-stage diagnoses and improve patient outcomes.

2.5. Conclusion

Timely diagnosis of cervical cancer is influenced by a complex interplay of individual behaviors, healthcare system capabilities, and societal factors. Addressing these challenges requires interdisciplinary collaboration, leveraging public health, sociology, behavioral science, and health policy frameworks.[21] Ethiopia’s fight against cervical cancer must prioritize integrated, multi-level interventions to reduce late-stage diagnoses and improve patient outcomes. By addressing identified barriers and reinforcing enablers, the country can align its efforts with global cervical cancer elimination goals.

3. Methodology

This study employed a mixed-methods research design incorporating both qualitative and quantitative approaches to comprehensively assess the factors influencing early or late diagnosis of cervical cancer in public health facilities in Addis Ababa. The methodology was structured around a literature review and primary data collection, integrating multiple sources of information to ensure a robust analysis of cervical cancer prevention, diagnosis patterns, barriers, and facilitators in the study setting.

The literature review involved an in-depth assessment of academic publications, national and international guidelines, Ph.D. dissertations, and government reports relevant to cervical cancer prevention, diagnosis, and control. The search strategy employed keywords such as “cervical cancer burden,” “HPV-related disease,” “screening and diagnosis,” and “treatment interventions.” Inclusion criteria focused on studies with appropriate designs that addressed the research questions, while exclusion criteria omitted articles lacking measurable outcomes or methodological rigor. To ensure data credibility, sources were cross-verified through online databases and institutional repositories, emphasizing systematic reviews and meta-analyses to capture global, regional, and national perspectives.

For primary data collection, a facility-based descriptive prospective study was conducted at four tertiary hospitals in Addis Ababa: Black Lion, Gandhi Memorial, St. Paul’s, and Zewditu Memorial Hospitals. Quantitative data were gathered from newly diagnosed cervical cancer patients through structured surveys, focusing on demographic, clinical, and behavioral factors influencing their diagnosis timing. The sample size was determined using a single population proportion formula, yielding a minimum of 384 participants, with proportional allocation based on patient volume at each hospital. To ensure quality, data collectors were trained in ethical considerations, confidentiality, and survey administration techniques.

The qualitative component comprised 22 in-depth interviews with cervical cancer patients, healthcare providers, and program managers from the four hospitals, the Ministry of Health, and the Addis Ababa Regional Health Bureau. Participants were purposively selected to provide diverse perspectives on diagnostic pathways, systemic barriers, and policy implications. Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured format, recorded with participant consent, and transcribed verbatim for analysis. Thematic coding and analysis were employed using ATLAS.ti software, ensuring consistency and reliability through a structured codebook that combined deductive and inductive approaches.

Data integration followed a convergent-explanatory mixed-methods approach, where qualitative findings complemented and explained patterns observed in quantitative data. Statistical analysis of survey responses was performed using SPSS, incorporating descriptive statistics, cross-tabulations, and logistic regression to identify predictors of early or late diagnosis. The study adhered to ethical guidelines, with approval obtained from relevant institutional review boards and informed consent secured from all participants. Through this rigorous methodology, the study aimed to provide actionable insights for policymakers and healthcare providers to enhance cervical cancer early detection and intervention efforts in Ethiopia and beyond.

4. Findings and Discussion

The findings from this mixed-methods study highlight significant patterns in the diagnosis of cervical cancer among patients attending public health facilities in Addis Ababa. With a 98.7% response rate, the quantitative data analysis included 386 responses, as no significant issues were found that necessitated exclusion. The qualitative aspect included 22 participants: 12 cervical cancer patients, eight healthcare providers, and two program managers. The patients represented early- and late-stage cases, providing insights into healthcare-seeking behavior and diagnostic and management challenges. Providers included gynecologic oncologists, general gynecologists, nurses, and program managers, offering perspectives on systemic healthcare barriers and potential improvements.

The findings of this study highlight critical disparities in awareness, access, and healthcare infrastructure that contribute to delayed diagnoses and suboptimal outcomes. The integration of the quantitative and qualitative findings in this study offers a nuanced understanding of the barriers to early diagnosis and the critical opportunities for intervention.

4.1. Patient Characteristics by Stage of Disease

Out of the 386 participants, 68.9% were diagnosed at an early stage (stage 1 and stage 2 cervical cancer disease), while 31.1% presented at a late stage (stage 3 and 4). This proportion aligns closely with findings in Uganda (30%) but is notably lower compared to a systematic review that reported a pooled prevalence of late-stage cervical cancer diagnosis in Ethiopia at 60.45% (95% CI: 53.04%–67.85%) and another study from a high-volume tertiary hospital in Addis Ababa, which identified a prevalence of 53.8%.[22],[23]

The mean age of participants was 51.47 years (SD = 10.12), with late-stage patients significantly older than early-stage patients (p = 0.005). Late-stage diagnosis was more common among those with lower educational attainment, as 45.8% of late-stage patients lacked formal education compared to 19.2% of early-stage patients. Economic challenges were also pronounced, with most patients earning below 5,000 ETB per month. Table 1 provides an overview of the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of participants.

The qualitative findings revealed that the majority of cervical cancer patients attending hospitals were from rural areas, supported by the quantitative data, which showed that 41.2% of participants resided outside Addis Ababa. However, the analysis did not find a statistically significant difference in the likelihood of being diagnosed with late-stage cervical cancer between participants living outside Addis Ababa and those diagnosed earlier. This finding contradicts previous studies in Ethiopia, which have generally highlighted geographic disparities, with rural residents being at higher risk for late-stage diagnosis.[24],[25]

The qualitative findings further indicate that many cervical cancer patients derive resilience from their spiritual beliefs, which serve as a critical source of emotional support and foster a positive outlook. This aligns with a study conducted on women experiencing gynecological cancer and their family caregivers, which affirmed that spirituality among gynecological cancer patients and their family caregiver dyads positively influences psychological resilience and hope.[26]

Table 1. Cervical Cancer Patients’ Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics by Disease Stage in Major Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from September to December 2024 (N=386).

| Characteristics | Stage Category | ||

| Early Stage (N, %) | Late Stage (N, %) | Total (%) | |

| Residence | |||

| Addis Ababa | 155 (68.3) | 72 (31.7) | 227 (58.8) |

| Outside Addis Ababa | 111 (63.9) | 48 (36.1) | 159 (41.2) |

| Mean Age in years | 50.51 (SD = 9.79) | 53.61 (SD = 10.55) | 51.47 (SD = 10.12) |

| Age Group | |||

| <39 years | 42 (15.8) | 14 (11.7) | 56 (14.5) |

| 40-49 years | 67 (25.2) | 24 (20.0) | 91 (23.6) |

| 50-59 years | 108 (40.6) | 38 (31.7) | 146 (37.8) |

| 60-69 years | 42 (15.8) | 34 (28.3) | 76 (19.7) |

| >70 years | 7 (2.6) | 10 (8.3) | 17 (4.4) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Not Married | 2 (0.8) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (1.0) |

| Married | 175 (65.8) | 71 (59.2) | 246 (63.7) |

| Separated | 14 (5.3) | 4 (3.3) | 18 (4.7) |

| Divorced | 16 (6.0) | 10 (8.3) | 26 (6.7) |

| Widowed | 59 (22.2) | 33 (27.5) | 92 (23.8) |

| Education | |||

| No Formal Education | 51 (19.2) | 55 (45.8) | 106 (27.5) |

| Primary Education | 125 (47.0) | 29 (24.2) | 154 (39.9) |

| Secondary Education | 69 (25.9) | 27 (22.5) | 96 (24.9) |

| Higher Education | 21 (7.9) | 9 (7.5) | 30 (7.8) |

| Monthly Income (ETB) | |||

| <5,000 | 218 (82.0) | 92 (76.7) | 310 (80.3) |

| 1-10,000 | 46 (17.3) | 27 (22.5) | 73 (18.9) |

| >10,000 | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) |

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 65 (24.4) | 27 (22.5) | 92 (23.8) |

| Unemployed | 179 (67.3) | 79 (65.81) | 258 (66.8) |

| Self-employed | 17 (6.4) | 4 (3.3) | 21 (5.4) |

| Retired | 5 (1.9) | 10 (8.3) | 15 (3.9) |

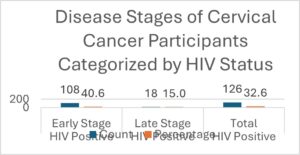

Regular Pap smear screening was a crucial factor influencing diagnosis timing, as 93.4% of those with routine screenings were diagnosed early, while nearly 47% of those without regular screening presented with late-stage disease. The starkest contrast was observed in participants who had never undergone a Pap smear. This group had the highest proportion of late-stage cervical cancer diagnoses, with 107 cases (89.2%) compared to 113 cases (42.5%) in the early stage. Close to a third (32.6%) of the participants were living with concurrent HIV/AIDS. Participants with a history of HIV/AIDS demonstrated a lower proportion of late-stage diagnoses, with 108 cases (40.6%) of early-stage and 18 cases (15.0%) of late-stage cervical cancer (Figure 1). These findings align with a systematic literature search and meta-analysis revealing that among approximately 14,000 (12,000–17,000) new cases of invasive cervical cancer, approximately one in four, 27.4% (23.7–31.7) of women from eastern Africa diagnosed with cervical cancer were living with HIV.[27] While this finding is consistent with a study conducted in Kenya that found most HIV-positive women diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer through screening had early-stage disease, it contrasts with the finding in the same study setting that revealed a 1.5 times more likelihood of identifying HIV-positive women at a late stage of cervical cancer disease.[28],[29] Cervical cancer prevention integrations in HIV care programs might have enabled targeted screening and early intervention for high-risk populations. These findings underscore the dual impact of regular Pap smear testing and a history of HIV/AIDS on cervical cancer staging, with WHO guidelines recommending that HIV-positive women undergo more frequent cervical cancer screenings due to their elevated risk.[30]

Figure 1. Disease Stages of Cervical Cancer Participants Categorized by HIV Status (N=386).

4.2. Factors Associated with Early or Delayed Diagnosis

Participants who underwent regular Pap smear screenings were over six times more likely to present with early-stage disease compared to those who did not (adjusted odds ratio (AOR)= 6.256, p < .001). Additionally, the time taken to seek care after noticing symptoms significantly influenced the likelihood of late-stage presentation. Individuals who delayed seeking care had 1.387 times higher odds of presenting at a late stage (AOR= 1.387, p = .008). The frequency of healthcare visits also played a significant role, with participants who made frequent healthcare visits having 1.594 times greater odds of presenting with early-stage disease (AOR= 1.594, p = .017).

Other factors, such as age group, education level, employment status, HIV/AIDS history, awareness of cervical cancer, and health insurance coverage, did not demonstrate statistically significant associations with the stage of diagnosis in the multivariate model (p > .05). Similarly, variables such as distance to the nearest healthcare facility, experience of healthcare access challenges, and the influence of cultural or religious beliefs on healthcare-seeking behavior were not significant predictors of late-stage presentation (p > .05) (Table 2).

Table 2. Consolidated Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Selected Predictors Associated with Late-stage Cervical Cancer Diagnosis in Major Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from September to December 2024 (N=386).

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | df | p-value | AOR |

| Age Group | 0.209 | 0.145 | 2.083 | 1 | 0.149 | 1.232 |

| Education Level | -0.134 | 0.181 | 0.542 | 1 | 0.461 | 0.875 |

| Employment Status | -0.187 | 0.196 | 0.913 | 1 | 0.339 | 0.829 |

| Regular Pap Smear Screening | 1.834 | 0.451 | 16.562 | 1 | 0.000** | 6.256 |

| HIV/AIDS History | 0.039 | 0.375 | 0.011 | 1 | 0.916 | 1.040 |

| Awareness of Cervical Cancer | -0.219 | 0.382 | 0.328 | 1 | 0.567 | 0.803 |

| Knowledge of Screening Tests | -0.208 | 0.373 | 0.310 | 1 | 0.577 | 0.812 |

| Frequency of Healthcare Visits | 0.466 | 0.195 | 5.713 | 1 | 0.017* | 1.594 |

| Time to Seek Care After Symptoms | 0.327 | 0.123 | 7.089 | 1 | 0.008** | 1.387 |

| Health Insurance Coverage | 0.210 | 0.290 | 0.521 | 1 | 0.470 | 1.233 |

| Distance to Healthcare Facility | -0.163 | 0.188 | 0.750 | 1 | 0.387 | 0.850 |

| Challenges in Healthcare Access | 0.157 | 0.347 | 0.205 | 1 | 0.651 | 1.170 |

| Cultural/Religious Beliefs Influence | -0.465 | 0.489 | 0.906 | 1 | 0.341 | 0.628 |

| Constant | -4.352 | 1.875 | 5.387 | 1 | 0.020* | 0.013 |

*Significant at p < 0.05 **Highly significant at p < 0.01

4.3. Patient and Community Factors Contributing to Late-Stage Presentation

Early-stage patients were significantly more likely to be aware of cervical cancer symptoms, screening programs, and the HPV vaccine than late-stage patients (p < 0.001). The results also suggest that education level plays a considerable role in determining the stage at which cervical cancer is diagnosed, potentially reflecting disparities in health awareness, access to screening, and healthcare-seeking behavior.

Presenting symptoms often get misinterpreted as one provider stated, “Patients often feel falsely reassured and delay seeking care, thinking they are normal…” (Provider_03). Despite the medical backgrounds of some participants, misconceptions about staging and symptoms persist, as one patient (a provider) stated: “I am a nurse by profession, and I believe I am in the early stages of the disease since I am only experiencing vaginal discharge…. I felt only slight fear because I held onto the hope that it was curable” (Patient_01). Studies in SSA have corroborated the role of awareness in fostering early diagnosis. This low level of awareness aligns with findings that noted only a minority (about 36%) of Ethiopian women are aware of cervical cancer screening services.[31] Similarly, another regional study identified knowledge gaps as a significant barrier in LMICs, emphasizing the need for targeted awareness campaigns.[32]

Qualitative insights further highlighted misconceptions, such as equating cervical cancer with divine punishment or associating screening procedures with infertility. In addition, cultural beliefs and stigma surrounding gynecological examinations also deterred timely health-seeking behavior. One healthcare provider stated, “Many patients believe cervical cancer is a result of witchcraft or divine punishment… which contributes to stigma and delays in seeking care” (Provider_08). Misconceptions about cervical cancer symptoms and the belief that symptoms would resolve without medical intervention contributed to delayed diagnosis. These observations are consistent with Burrowes et al who documented how cultural beliefs and stigmatizations impede health-seeking behaviors in Ethiopia.[33]

Family obligations and financial stress also played a role, as some patients prioritized household needs over their health delaying seeking services. Limited community awareness about cervical cancer further exacerbated delays, with patients expressing reluctance to discuss their symptoms due to stigma.[34]

4.4. Health System Factors Contributing to Late-Stage Presentation

Although patients generally reported positive experiences with healthcare providers, financial barriers and inefficiencies in service delivery, such as long waiting times, insufficient diagnostic services, and referral delays, were key contributors to late-stage diagnosis (Table 3). This finding aligns with other studies conducted in resource-limited settings.[35]

Regular Pap smear screening is identified as a key protective factor in the quantitative part of this study which aligns with findings from Eiman, Bhatla et al., and WHO recommendations, which emphasize accessible and routine preventive services. [36],[37],[38] However, providers cited equipment shortages and delays in radiotherapy access as major obstacles. A provider noted, “A significant drawback of the HPV DNA test is the long turnaround time (TAT) for results from the regional laboratory. Delays of over two months may cause women to forget to follow up on their results, which can negatively affect our HPV DNA-positive clients” (Provider_03). Expanding access to advanced diagnostic tools like HPV DNA testing, which offers higher sensitivity and specificity compared to traditional methods, could enhance screening reliability. [39]

A manager noted, “Many women feel shy about participating in screening, so policy changes that support self-sampling for HPV DNA tests will undoubtedly improve the program’s effectiveness” (Manager_02). The same respondent highlights the challenge of the absence of clear guidance in screening older targets: “Currently, screening services focus primarily on women aged 30 to 49. For women beyond reproductive age, screening is often conducted without clear guidance. We need to enhance screening for older women.” Incorporating these advanced tools into cervical cancer screening programs could significantly improve outcomes, particularly to include older women (aged 30-60), with appropriate guidelines, is crucial for comprehensive cervical cancer prevention.[40]

The quantitative results further revealed that geographic and logistical obstacles significantly contribute to the late-stage presentation. Inadequate screening infrastructure and long distances to healthcare facilities emerged as key determinants of delayed diagnosis, aligning with findings from WHO reports on LMICs and a systematic review conducted in SSA by Lombe DC and colleagues.[41],[42] A lack of trained specialists and limited screening infrastructure further complicated timely detection efforts, and providers underscore the importance of expanding radiotherapy facilities and training more specialized healthcare providers as noted by a gynecologic oncologist:

“This hospital is the only facility in Addis Ababa, the capital, that offers radiotherapy, making access extremely challenging. Oncology units are available only here and at one other hospital in the city, and this limited infrastructure, combined with scarce human resources, places a heavy burden on the program” (Provider_07).

Clear referral pathways are essential to ensure timely and appropriate care for cervical cancer patients. A study in Zambia underscores the effectiveness of deploying liaison officers within healthcare facilities to manage patient referrals. Qualitative interviews from the study suggest that health facilities should appoint liaison officers, similar to those in obstetric services, to notify receiving facilities by phone, ensuring that referred cervical cancer patients are promptly connected to necessary healthcare services.[43] A program manager expressed optimism about addressing this challenge:

“We are developing a referral directory to serve as a comprehensive catalog, and efforts are underway to promote awareness about it. This directory will guide patients to the right facility based on their disease stage. It is designed for implementation across all sub-national levels, streamlining both diagnostic and therapeutic referrals” (Manager_01).

4.5. Barriers to Timely Diagnosis

Financial constraints, transportation issues, and fear of diagnosis emerged as major barriers to timely cervical cancer screening and diagnosis (Table 3). Many patients expressed concerns about the cost of treatment, while others cited long travel distances to specialized facilities as deterrents, consistent with findings from previous studies on screening barriers in low-resource settings.[44] One healthcare provider highlighted: “Many cannot afford to stay in the city for a full diagnostic workup…” (Provider_07). The lack of comprehensive health insurance coverage further exacerbates the issue. Other respondents explained: “Our health insurance does not cover advanced treatments, which significantly impacts timely access to care” (Providers 04 and 08). Research has shown that in LMICs, financial burdens remain a primary obstacle to screening participation.[45]

Psychological barriers, such as fear of a cancer diagnosis, also prevent timely health-seeking behavior. In conservative communities, social norms discourage women from accessing screening services. Fear of screening procedures and widespread misinformation about cervical cancer were common themes, aligning with recent studies on declining screening rates and perspectives on self-sampling interventions.[46] One respondent explained, “Women remain shy to expose their bodies and fear the speculum examination itself” (Manager 02). A provider shared a potential solution: “I recommend using expandable plastic equipment for examinations instead, as it could minimize pain and discomfort” (Provider 06). Additionally, deeply rooted beliefs in alternative treatments, such as holy water, often delay medical intervention. Confusion between precancerous and cancerous conditions further hinders early detection efforts, as highlighted in studies exploring barriers in resource-limited settings.[47] The same provider shared, “Some cervical cancer patients initially sought treatment at religious places, delaying proper care” (Provider 06).

Interestingly, qualitative respondents noted that most cervical pre-cancer or cancer cases involved patients with slim body habitus in the study setting, which they reported as not posing significant challenges for diagnosis or treatment. This observation contrasts with findings from a study assessing providers’ perspectives, where approximately 80% of respondents reported challenges in performing cervical biopsies or accessing the cervix in obese patients. These difficulties were often attributed to the lack of sufficiently long sampling devices and adequately sized speculums.[48]

4.6. Role of Partnerships and Stakeholders

As summarized in Table 3, collaborative efforts between public and private healthcare providers were highlighted as a strategy to expand screening and treatment accessibility. Consistent with the insights of Lewis et al., this study found that partnerships among NGOs, government agencies, and community leaders significantly enhance outreach efforts.[49] Social support networks, including family and religious institutions, were identified as influential in encouraging women to seek care, aligning with the collaborative frameworks recommended by the WHO.[50] A patient shared, “The community should support such patients both financially and psychosocially” Patient_10. Other patients expressed, “My husband, along with my family and friends reassures me that this can happen to any woman; …. and that I will be cured of the disease soon” (Patients_01 and _05).

Fragmented coordination and resource limitations remain substantial barriers that hinder the effectiveness of these efforts, as emphasized by Lombe et al.[51] Program managers in this study echoed this sentiment, emphasizing the necessity of collective efforts, with one stating, “Comprehensive care cannot be achieved by the government alone” (Manager_01).

Providers also emphasized the importance of task-sharing and utilizing community health workers (CHWs) to strengthen service delivery. In urban settings, a manager shared the experience of the multidisciplinary team that visits communities integrating screening services: “… Additionally we employ a strategy known as the ‘family health team’, which consists of various health professionals who, following established guidelines, visit the community to identify and recruit eligible women for screening” (Manager_02). Additionally, leveraging technology such as telemedicine and mobile health applications offers promising avenues for improving service delivery and patient outcomes as indicated in the qualitative interview with providers in this study. Evidence from a systematic review suggests that the involvement of CHWs in screening efforts across LMICs is both feasible and acceptable. However, adopting participatory approaches in the design of CHW interventions could enhance their acceptability and effectiveness.[52]

Table 3. Summary of Themes and Key Findings from the Qualitative Interviews.

| Major Theme | Key Findings |

| Patient Experiences | – Emotional reactions to diagnosis: shock, despair, fear, and occasional relief after treatment initiation. |

| – Financial stress: cost of treatment, childcare, and emotional burden. | |

| – Disease disclosure: stigma, social repercussions, and selective disclosure to family or friends. | |

| – Coping strategies: reliance on faith, spiritual beliefs, and family support. | |

| Community and Cultural Barriers | – Social stigma: fear of community judgment and lack of disclosure. |

| – Myths and misconceptions: beliefs about witchcraft, divine punishment, and ART as a universal cure. | |

| – Gender disparities: women prioritizing family over personal health, cultural resistance to screenings. | |

| – Role of religious and cultural leaders: influential in promoting health education and dispelling myths. | |

| Healthcare System Challenges | – Service delays: insufficient diagnostic and treatment facilities, delays in laboratory tests, and limited availability of specialized care. |

| – Resource constraints: shortages of equipment, such as colposcopes and speculums, and lack of trained personnel. | |

| – Inefficient referral systems: fragmented coordination between facilities and lack of timely communication. | |

| – Staff turnover and burnout: lack of mentorship, professional development, and incentives for healthcare workers. | |

| Awareness and Literacy | – Low health literacy: confusion between “precancer” and cancer, lack of symptom awareness. |

| – Misconceptions: treatment fears, belief in infertility caused by procedures, and vaccination; and low-risk perception. | |

| – Limited access to education and health care: disparities between rural and urban populations in understanding prevention and care. | |

| Financial and Logistical Issues | – High costs: diagnostic tests, medications, and advanced treatments are financially prohibitive. |

| – Transportation challenges: long distances to facilities, lack of funds for travel, and extended wait times. | |

| – Limited health insurance coverage: gaps in support for advanced cervical cancer treatments. | |

| Stakeholder Collaboration | – Partnerships: the necessity of coordinated efforts among government, NGOs, CSOs, and private sectors. |

| – Community health workers: potential to address access gaps through task-shifting and outreach programs. | |

| – Integration efforts: combining cervical cancer prevention with other health initiatives like HIV care. | |

| – Advocacy and education: consistent media campaigns to combat misinformation and improve public awareness. |

4.7. Inductive Output

The integration of quantitative and qualitative data in this study underscored the importance of regular screening, early intervention, and education in reducing late-stage diagnoses. Technological advancements, such as HPV DNA testing, were recognized as potential game-changers in improving screening rates.

The role of multi-stakeholder collaboration in policy development and advocacy was also emphasized. Advocacy for subsidized healthcare, integrated care models, and expanded insurance coverage can ensure equitable access to cervical cancer diagnosis and treatment.

4.8. Dialectical Evaluation

The study revealed contradictions in healthcare access and patient experiences. While integrated HIV care programs facilitated early cervical cancer screening, the stigma associated with both diseases continued to discourage some women from seeking timely care. This contrasts with expectations that routine monitoring would entirely mitigate late-stage diagnoses. Another paradox involves the role of education: although higher education levels correlate with earlier diagnoses, qualitative data indicate that even educated healthcare workers occasionally overlook symptoms and stages of the disease, highlighting gaps in awareness even among medical professionals. Geographic disparities in diagnosis patterns suggested that urban-rural access differences were not as pronounced as expected, likely due to increased outreach and awareness initiatives. These findings highlight the complexity of cervical cancer prevention and the need for targeted, culturally sensitive interventions to bridge knowledge and healthcare gaps.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusion

This study highlights the complex interplay of individual, systemic, and socioeconomic factors influencing the early or late diagnosis of cervical cancer in public health facilities in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The findings underscore the critical role of regular Pap smear screening in early detection, with those undergoing annual screening exhibiting the highest likelihood of early-stage diagnosis. Conversely, delayed healthcare-seeking behavior, low educational attainment, and financial barriers were key predictors of late-stage presentation.

The qualitative data provide further context by illustrating how misconceptions, stigma, and healthcare infrastructure deficiencies contribute to diagnostic delays. Cultural beliefs linking cervical cancer to supernatural causes, fear of infertility, and lack of awareness about preventive measures deter many women from seeking timely medical attention. Additionally, systemic barriers such as inadequate diagnostic tools, staff shortages, and inefficient referral systems disproportionately impact rural and underserved populations, exacerbating delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Integrated findings suggest that targeted interventions, including increased awareness campaigns, expanded screening programs, and enhanced healthcare infrastructure are essential to bridging these gaps. Moreover, the protective effect of HIV/AIDS-related healthcare engagement highlights the potential of leveraging existing chronic disease management programs to improve cervical cancer outcomes.

By addressing these multi-faceted barriers, Ethiopia can enhance early detection rates, reduce disparities, and align with the WHO’s global cervical cancer elimination strategy. The study’s findings have broader implications beyond Ethiopia, offering valuable insights into the challenges faced by low-resource settings worldwide.

5.2. Recommendations

To mitigate the burden of late cervical cancer diagnosis, this study recommends a multi-pronged approach addressing awareness, accessibility, healthcare infrastructure, and policy-level interventions.

Public education campaigns should be intensified to promote routine screening, HPV vaccination, and early symptom recognition. These efforts should be culturally tailored and integrated into school curricula, community-based initiatives, and digital media platforms to maximize reach and impact. Engaging religious and cultural leaders can further dispel myths and reduce stigma, encouraging women to seek timely medical care.

To improve access to preventive services, healthcare systems must be decentralized. Mobile screening clinics and portable diagnostic tools should be deployed to reach remote communities. Financial barriers should also be addressed through subsidies, free screening programs, and expanded health insurance coverage. Integrating cervical cancer screening into HIV and maternal healthcare services can reduce missed opportunities and enhance early detection rates.

Strengthening healthcare infrastructure is essential. Investment in diagnostic equipment, increased training for healthcare providers, and task-sharing initiatives can improve service delivery. Establishing additional radiotherapy centers will enhance treatment capacity. Moreover, efficient referral networks must be developed to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment, particularly for patients from rural areas.

Multi-sectoral collaboration is crucial to sustainable cervical cancer prevention. Public-private partnerships should be leveraged to expand healthcare infrastructure and service provision. Community health workers can play a key role in outreach, education, and patient follow-up, ensuring continuity of care. Strengthening civil society engagement and aligning national strategies with global health initiatives will further enhance program effectiveness.

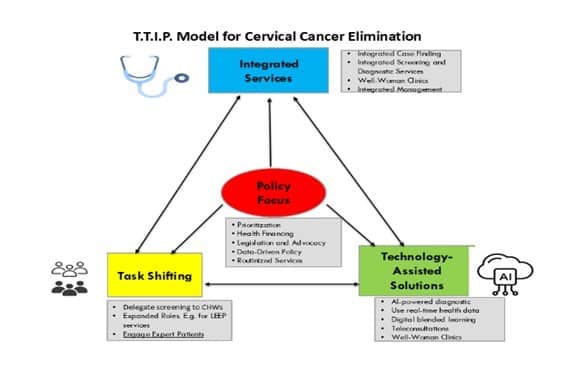

A key framework guiding these interventions is the TTIP Model for Cervical Cancer Elimination (Figure 2), which outlines four interrelated pillars: Technology-Assisted Solutions, Task Shifting, Integrated Services, and Policy Focus. This model provides a structured approach to improving cervical cancer prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment by leveraging technology, expanding healthcare workforce capacity, integrating screening into existing health programs, and advocating for supportive policies.

Figure 2. The TTIP Model for Cervical Cancer Elimination.

5.3. Implications

The study’s findings hold significant implications for public health, healthcare systems, and policy development. Expanding awareness and screening programs is imperative, as the data demonstrate that regular Pap smear screenings dramatically increase the likelihood of early diagnosis. Addressing misconceptions and stigma through targeted education campaigns can further encourage early care-seeking behavior.

Sociodemographic and geographic disparities must also be tackled. Policies should prioritize healthcare equity by subsidizing screening services, expanding mobile clinics, and improving outreach in rural areas. Integrating cervical cancer screening with existing healthcare programs—such as HIV and maternal health services—offers a practical approach to increasing access and reducing disparities.

The psychological and cultural barriers identified in the study necessitate psychosocial interventions that incorporate mental health support and culturally sensitive care models. Community-driven approaches that engage local leaders can foster greater acceptance of preventive measures and improve patient adherence to prevention and timely care seeking.

From a policy perspective, investments in healthcare infrastructure, workforce expansion, and task-shifting initiatives are essential to strengthening cervical cancer services. Including and expanding the scope of health insurance schemes for cervical cancer care will further improve accessibility. Moreover, extending the upper age limit for women to be screened can lead to better detection rates. Additionally, promoting the use of HPV self-sampling kits and other technological innovations can boost screening participation and improve diagnostic accuracy, especially in resource-limited areas.

5.4. Contributions and Limitations

This research offers a comprehensive analysis of determinants influencing cervical cancer diagnosis from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. By examining individual, systemic, and cultural barriers, it provides actionable recommendations to improve screening uptake, reduce delays, and enhance patient outcomes. The findings contribute to discussions on healthcare disparities and support national and global cervical cancer control initiatives.

The study’s robust dataset, high participation rate, and comparative analysis between early- and late-stage diagnosis groups strengthen its contributions to the field. Moreover, by including perspectives from both Addis Ababa and surrounding regions, the research provides context-specific insights applicable to other low-resource settings.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design prevents causal inference between variables and cervical cancer staging. Self-reported data on screening history and healthcare-seeking behavior may be subject to recall bias. Additionally, the study’s focus on public health facilities limits generalizability to patients receiving care in private institutions. Future research should explore longitudinal patient outcomes, assess intervention effectiveness, and further investigate behavioral determinants influencing screening adherence.

Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable contributions to cervical cancer prevention efforts. By addressing systemic and individual barriers through the TTIP Model, Ethiopia can make significant strides toward earlier diagnosis, improved patient outcomes, and alignment with global cervical cancer elimination targets.

6. Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

7. Acknowledgment

I acknowledge all the support from Euclid University and my supervising professor, Prof. Laurent Cleenewerck, in completing the dissertation from which this paper was derived.

Bibliography

Andersen, R. M. “Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36, no. 1 (March 1995): 1–10.

Begoihn, M, A Mathewos, A Aynalem, and T Wondemagegnehu. “Cervical Cancer in Ethiopia–Predictors of Advanced Stage and Prolonged Time to Diagnosis.” Infectious Agents and Cancer 14, no. 36 (2019). https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1186/s13027-019-0255-4.

Bhatla, N, D Aoki, DN Sharma, and R Sankaranarayanan. “Cancer of the Cervix Uteri: 2021 Update.” Int J Gynaecol Obstet., 2021. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13865. PMID.

Bronfenbrenner, Urie. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Harvard University Press, 1979. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv26071r6.

Burrowes, Sahai, Sarah Jane Holcombe, Cheru Tesema Leshargie, Alexandra Hernandez, Anthony Ho, Molly Galivan, Fatuma Youb, and Eiman Mahmoud. “Perceptions of Cervical Cancer Care among Ethiopian Women and Their Providers: A Qualitative Study.” Reproductive Health 19, no. 1 (January 4, 2022): 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01316-3.

“Cancer Nursing.” Accessed December 18, 2024. https://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/abstract/9900/effect_of_spirituality_on_psychological_resilience.254.aspx.

Chorley, Amanda J., Laura A. V. Marlow, Alice S. Forster, Jessica B. Haddrell, and Jo Waller. “Experiences of Cervical Screening and Barriers to Participation in the Context of an Organised Programme: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis.” Psycho-Oncology 26, no. 2 (2017): 161–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4126.

Clarke, MA, LS Massad, MJ Khan, KM Smith, RS Guido, EJ Mayeaux, TM Darragh, and WK Huh. “Challenges Associated With Cervical Cancer Screening and Management in Obese Women: A Provider Perspective.” J Low Genit Tract Dis. 24, no. 2 (2020): 184–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000506. PMID: 32243314.

“Delays in Seeking, Reaching and Access to Quality Cancer Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review – PubMed.” Accessed December 18, 2024. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37055211/.

Dereje, Nebiyu, Adamu Addissie, Alemayehu Worku, Mathewos Assefa, Aynalem Abraha, Wondemagegnehu Tigeneh, EJ Kantelhardt, and Ahmedin Jemal. “Extent and Predictors of Delays in Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Population-Based Prospective Study.” JCO Global Oncology 6 (2020): 277–84.

Duncan, Kalina. “Facilitators Enabling Sustainable Cervical Cancer Control Programs In Low And Middle-Income Countries: Strengthening Health Systems In Zambia.” PhD Diss. Gillings School of Global Public Health, 2022. https://doi.org/10.17615/kjmc-mg63.

Eiman, Elmarie. “Assessment of Risk Factors Associated with Cervical Cancer amongst Women Attending the Oncology Center and Health Facilities in Windhoek, Khomas Region.” PhD Diss., The University of Namibia, 2020.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. “Guideline for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control in Ethiopia.” Ministry of Health, 2021.

———. “National Cancer Control Plan (2016-2020).” Ministry of Health, 2015.

Feuchtner, J, A Mathewos, A Solomon, G Timotewos, A Aynalem, and T Wondemagegnehu. “Addis Ababa Population-Based Pattern of Cancer Therapy, Ethiopia.” PLoS One, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219519.

Fitiwe, Wintana. “Magnitude and Factors Associated with Late Stage at Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer Patients at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.” Addis Abeba University, 2020. http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/26001.

Getachew, Theodros, Abebe Bekele, Kassahun Amenu, and Atkure Defar. “Service Availability and Readiness for Major Non-Communicable Diseases at Health Facilities in Ethiopia.” Ethiopian Journal of Health Development Vol. 31 No.1 (2017). https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/167853.

Ghosh, Supriti, Sneha D. Mallya, Sanjay M. Pattanshetty, and Deeksha Pandey. “Awareness, Attitude, and Practice towards Cancer Cervix Prevention among Rural Women in Southern India: A Community-Based Study.” Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 26 (March 1, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2024.101546.

Gravitt, Patti E., Proma Paul, Hormuzd A. Katki, Haripriya Vendantham, Gayatri Ramakrishna, Mrudula Sudula, Basany Kalpana, Brigitte M. Ronnett, K. Vijayaraghavan, and Keerti V. Shah. “Effectiveness of VIA, Pap, and HPV DNA Testing in a Cervical Cancer Screening Program in a Peri-Urban Community in Andhra Pradesh, India.” PLoS ONE 5, no. 10 (October 28, 2010): e13711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013711.

Kassa, Rahel Nega, Desalegn Markos Shifti, Kassahun Alemu, and Akinyinka O. Omigbodun. “Integration of Cervical Cancer Screening into Healthcare Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review.” PLOS Global Public Health 4, no. 5 (May 14, 2024): e0003183. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003183.

Lewis, H. et al. “Stakeholder Engagement in Cervical Cancer Prevention.” The Lancet Oncology 21 (2020): 22–36.

Mantula, Fennie, Yoesrie Toefy, and Vikash Sewram. “Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Africa: A Systematic Review.” BMC Public Health 24, no. 1 (February 20, 2024): 525. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17842-1.

Mihretie, G.N., T.M. Liyeh, A.D. Ayele, H.G. Belay, T.S. Yimer, and A.D. Miskr. “Knowledge and Willingness of Parents towards Child Girl HPV Vaccination in Debre Tabor Town, Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study.” Reproductive Health 9, no. 1 (2022). https://doi.org/, 19(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01444-4.

Mungo, Chemtai, Craig R. Cohen, May Maloba, Elizabeth A. Bukusi, and Megan J. Huchko. “Prevalence, Characteristics, and Outcomes of HIV-Positive Women Diagnosed with Invasive Cancer of the Cervix in Kenya.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 123, no. 3 (December 1, 2013): 231–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.010.

O’Donovan, James, Charles O’Donovan, and Shobhana Nagraj. “The Role of Community Health Workers in Cervical Cancer Screening in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Literature.” BMJ Global Health 4, no. 3 (2019): e001452. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001452.

Petersen, Z., A. Jaca, T. G. Ginindza, G. Maseko, S. Takatshana, P. Ndlovu, N. Zondi, et al. “Barriers to Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening Services in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review.” BMC Women’s Health 22, no. 1 (December 2, 2022): 486. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02043-y.

Rose, Anorlu. “Cervical Cancer: The Sub-Saharan African Perspective.” Reproductive Health Matters 16, no. 32 (2008): 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32415-X.

Sharma, R, Aashima, M Nanda, C Fronterre, P Sewagudde, A.E. Ssentongo, K Yenney, N.D. Arhin, F. Amponsah-Manu, and P. Ssentongo. “Mapping Cancer in Africa: A Comprehensive and Comparable Characterization of 34 Cancer Types Using Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020.” Frontiers in Public Health, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.839835.

Stelzle, Dominik, Luana F. Tanaka, Kuan Ken Lee, Ahmadaye Ibrahim Khalil, Iacopo Baussano, Anoop S. V. Shah, David A. McAllister, et al. “Estimates of the Global Burden of Cervical Cancer Associated with HIV.” The Lancet Global Health 9, no. 2 (February 1, 2021): e161–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30459-9.

“Teklu et al. – 2020 – National Assessment of the Ethiopian Health Extens.Pdf,” n.d.

UICC 2022. “Cervical Cancer Elimination in Africa: Where Are We Now and Where Do We Need to Be?” UICC. Accessed May 11, 2024. https://www.uicc.org/news/cervical-cancer-elimination-africa-where-are-we-now-and-where-do-we-need-be.

Vega Crespo, Bernardo, Vivian Alejandra Neira, José Ortíz Segarra, Andrés Andrade, Gabriela Guerra, Stalin Ortiz, Antonieta Flores, et al. “Barriers and Facilitators to Cervical Cancer Screening among Under-Screened Women in Cuenca, Ecuador: The Perspectives of Women and Health Professionals.” BMC Public Health 22, no. 1 (November 22, 2022): 2144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14601-y.

World Health Organization. “Cervical Cancer Fact Sheet,” 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer#:~:text=Key%20facts%201%20Cervical%20cancer%20is%20the%20fourth,with%20the%20human%20papillomavirus%20%28HPV%29.%20…%20More%20items.

———. “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem.” Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

———. “International Agency for Research on Cancer.” Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

———. “WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention, Second Edition.” Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021.

———. “World Health Organization – Cervical Cancer Country Profiles, 2021.” Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/cxca/cxca-profiles/cxca-profiles-en.pdf?sfvrsn=d65f786_23&download=true.

“World Health Organization Strategy for Engaging Religious Leaders, Faith-Based Organizations and Faith Communities in Health Emergencies.” Accessed December 18, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037205.

Zewdie, Amare, Solomon Shitu, Natnael Kebede, Anteneh Gashaw, Habitu Birhan Eshetu, Tenagnework Eseyneh, and Abebaw Wasie Kasahun. “Determinants of Late-Stage Cervical Cancer Presentation in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMC Cancer 23, no. 1 (December 14, 2023): 1228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11728-y.

[1] World Health Organization, “Cervical Cancer Fact Sheet,” 2024, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer#:~:text=Key%20facts%201%20Cervical%20cancer%20is%20the%20fourth,with%20the%20human%20papillomavirus%20%28HPV%29.%20…%20More%20items.

[2] R Sharma et al., “Mapping Cancer in Africa: A Comprehensive and Comparable Characterization of 34 Cancer Types Using Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020,” Frontiers in Public Health, 2022, 3–9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.839835.

[3] World Health Organization, “World Health Organization – Cervical Cancer Country Profiles, 2021” (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021), 60, https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/ncd-surveillance/cxca/cxca-profiles/cxca-profiles-en.pdf?sfvrsn=d65f786_23&download=true.

[4] Amare Zewdie et al., “Determinants of Late-Stage Cervical Cancer Presentation in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” BMC Cancer 23, no. 1 (December 14, 2023): 4–6, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-023-11728-y.

[5] Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, “National Cancer Control Plan (2016-2020)” (Ministry of Health, 2015), 14.

[6] UICC 2022, “Cervical Cancer Elimination in Africa: Where Are We Now and Where Do We Need to Be?,” UICC, accessed May 11, 2024, https://www.uicc.org/news/cervical-cancer-elimination-africa-where-are-we-now-and-where-do-we-need-be.

[7] Anorlu Rose, “Cervical Cancer: The Sub-Saharan African Perspective,” Reproductive Health Matters 16, no. 32 (2008): 44, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(08)32415-X.

[8] G.N. Mihretie et al., “Knowledge and Willingness of Parents towards Child Girl HPV Vaccination in Debre Tabor Town, Ethiopia: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study.,” Reproductive Health 9, no. 1 (2022): 8, https://doi.org/, 19(1), 136. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01444-4.

[9] J Feuchtner et al., “Addis Ababa Population-Based Pattern of Cancer Therapy, Ethiopia.,” PLoS One, 2019, 6, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219519.

[10] World Health Organization, “International Agency for Research on Cancer” (Geneva, Switzerland, 2022), https://gco.iarc.fr/today.

[11] World Health Organization, “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem” (Geneva, Switzerland, 2020).

[12] Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, “Guideline for Cervical Cancer Prevention and Control in Ethiopia” (Ministry of Health, 2021), 16.

[13] “Teklu et al. – 2020 – National Assessment of the Ethiopian Health Extens.Pdf,” n.d., 381.

[14] Theodros Getachew et al., “Service Availability and Readiness for Major Non-Communicable Diseases at Health Facilities in Ethiopia,” Ethiopian Journal of Health Development Vol. 31 No.1 (2017): 386–87, https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ejhd/article/view/167853.

[15] “World Health Organization Strategy for Engaging Religious Leaders, Faith-Based Organizations and Faith Communities in Health Emergencies,” accessed December 18, 2024, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037205.

[16] World Health Organization, “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem,” 7.

[17] World Health Organization, “Cervical Cancer Fact Sheet.”

[18] M Begoihn et al., “Cervical Cancer in Ethiopia–Predictors of Advanced Stage and Prolonged Time to Diagnosis,” Infectious Agents and Cancer 14, no. 36 (2019): 4, https://doi.org/doi.org/10.1186/s13027-019-0255-4.

[19] Urie Bronfenbrenner, The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Harvard University Press, 1979), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv26071r6.

[20] R. M. Andersen, “Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter?,” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36, no. 1 (March 1995): 1–10.

[21] World Health Organization, “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem,” 6.

[22] UICC 2022, “Cervical Cancer Elimination in Africa: Where Are We Now and Where Do We Need to Be?,” 18.

[23] Wintana Fitiwe, “Magnitude and Factors Associated with Late Stage at Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer Patients at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia” (Addis Abeba University, 2020), http://etd.aau.edu.et/handle/123456789/26001.

[24] Zewdie et al., “Determinants of Late-Stage Cervical Cancer Presentation in Ethiopia,” 5.

[25] Fitiwe, “Magnitude and Factors Associated with Late Stage at Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer Patients at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.”

[26] “Cancer Nursing,” accessed December 18, 2024, https://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/abstract/9900/effect_of_spirituality_on_psychological_resilience.254.aspx.

[27] Dominik Stelzle et al., “Estimates of the Global Burden of Cervical Cancer Associated with HIV,” The Lancet Global Health 9, no. 2 (February 1, 2021): 9, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30459-9.

[28] Begoihn et al., “Cervical Cancer in Ethiopia–Predictors of Advanced Stage and Prolonged Time to Diagnosis,” 4.

[29] Chemtai Mungo et al., “Prevalence, Characteristics, and Outcomes of HIV-Positive Women Diagnosed with Invasive Cancer of the Cervix in Kenya,” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 123, no. 3 (December 1, 2013): 231–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.07.010.

[30] World Health Organization, “WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention, Second Edition” (Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021).

[31] Nebiyu Dereje et al., “Extent and Predictors of Delays in Diagnosis of Cervical Cancer in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A Population-Based Prospective Study.,” JCO Global Oncology 6 (2020): 279.

[32] Sharma et al., “Mapping Cancer in Africa: A Comprehensive and Comparable Characterization of 34 Cancer Types Using Estimates From GLOBOCAN 2020,” 10–12.

[33] Sahai Burrowes et al., “Perceptions of Cervical Cancer Care among Ethiopian Women and Their Providers: A Qualitative Study,” Reproductive Health 19, no. 1 (January 4, 2022): 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01316-3.

[34] Supriti Ghosh et al., “Awareness, Attitude, and Practice towards Cancer Cervix Prevention among Rural Women in Southern India: A Community-Based Study,” Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health 26 (March 1, 2024), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2024.101546.

[35] Kalina Duncan, “Facilitators Enabling Sustainable Cervical Cancer Control Programs In Low And Middle-Income Countries: Strengthening Health Systems In Zambia.,” PhD Diss. Gillings School of Global Public Health, 2022, 91, https://doi.org/10.17615/kjmc-mg63.

[36] N Bhatla et al., “Cancer of the Cervix Uteri: 2021 Update.,” Int J Gynaecol Obstet., 2021, 9, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13865. PMID.

[37] World Health Organization, “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem,” 28.

[38] Elmarie Eiman, “Assessment of Risk Factors Associated with Cervical Cancer amongst Women Attending the Oncology Center and Health Facilities in Windhoek, Khomas Region,” PhD Diss., The University of Namibia, 2020, 12–15.

[39] Patti E. Gravitt et al., “Effectiveness of VIA, Pap, and HPV DNA Testing in a Cervical Cancer Screening Program in a Peri-Urban Community in Andhra Pradesh, India,” PLoS ONE 5, no. 10 (October 28, 2010): 6, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013711.

[40] World Health Organization, “WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention, Second Edition,” 3.

[41] World Health Organization, “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem,” 49,50.

[42] “Delays in Seeking, Reaching and Access to Quality Cancer Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review – PubMed,” 2–8, accessed December 18, 2024, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37055211/.

[43] Rahel Nega Kassa et al., “Integration of Cervical Cancer Screening into Healthcare Facilities in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review,” PLOS Global Public Health 4, no. 5 (May 14, 2024): 4(5), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003183.

[44] Fennie Mantula, Yoesrie Toefy, and Vikash Sewram, “Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening in Africa: A Systematic Review,” BMC Public Health 24, no. 1 (February 20, 2024): 525, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17842-1.

[45] Z. Petersen et al., “Barriers to Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening Services in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review,” BMC Women’s Health 22, no. 1 (December 2, 2022): 486, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-02043-y.

[46] Amanda J. Chorley et al., “Experiences of Cervical Screening and Barriers to Participation in the Context of an Organised Programme: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis,” Psycho-Oncology 26, no. 2 (2017): 161–72, https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4126.

[47] Bernardo Vega Crespo et al., “Barriers and Facilitators to Cervical Cancer Screening among Under-Screened Women in Cuenca, Ecuador: The Perspectives of Women and Health Professionals,” BMC Public Health 22, no. 1 (November 22, 2022): 2144, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14601-y.

[48] MA Clarke et al., “Challenges Associated With Cervical Cancer Screening and Management in Obese Women: A Provider Perspective.,” J Low Genit Tract Dis. 24, no. 2 (2020): 185, https://doi.org/10.1097/LGT.0000000000000506. PMID: 32243314.

[49] Lewis, H. et al., “Stakeholder Engagement in Cervical Cancer Prevention,” The Lancet Oncology 21 (2020): 22–36.

[50] World Health Organization, “Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem,” 37.

[51] “Delays in Seeking, Reaching and Access to Quality Cancer Care in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review – PubMed,” 2–8.

[52] James O’Donovan, Charles O’Donovan, and Shobhana Nagraj, “The Role of Community Health Workers in Cervical Cancer Screening in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Scoping Review of the Literature,” BMJ Global Health 4, no. 3 (2019): 7, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001452.