ABSTRACT

| Vietnam’s post-1986 transition from a war-torn, centrally planned economy to a market-oriented system following the “Doi Moi” (reforms) offers a compelling case study in development economics. This paper analyzes Vietnam’s substantial achievements in poverty alleviation, public health, and socioeconomic advancement, which were facilitated by strategic economic diplomacy, foreign direct investment (FDI), and focused interventions. Despite this progress, significant challenges persist, including persistent rural-urban disparities, environmental degradation, and social inequality among ethnic minorities. Utilizing foundational theories from development economics, such as Sen’s capability approach and the Lewis dual-sector model, this study proposes policy recommendations for ensuring equitable and sustainable growth. These suggestions include initiatives for equitable resource allocation, targeted public-private partnerships, the expansion of telemedicine, and the strengthening of social safety nets, all designed to address Vietnam’s specific challenges while supporting global sustainability objectives. | |

- Introduction

Vietnam’s transformation from a war-torn, centrally planned economy to a lively, market-oriented country shows how development economics works in real life. The Doi Moi (reforms), which started in 1986, were a significant step toward policies that favored the market, gave people more power over economic decisions, and brought Vietnam into the global economy. These changes have led to strong GDP growth, a significant drop in poverty, and better health and education outcomes for the people. This study examines Vietnam’s extraordinary accomplishments in development economics, its global diplomatic strategy, and sustainable development participation, delineates persistent obstacles, and suggests sustainable and equitable long-term growth options. Vietnam’s success has been mainly due to its wise economic diplomacy, including targeted trade agreements, foreign direct investment (FDI), and active participation in global and regional economic forums. These things have helped the economy grow, raised Vietnam’s profile worldwide, and made it more resilient.

- Situations and Problems

Prior to the 1980s, Vietnam faced severe socioeconomic challenges due to the Vietnam War (1955–1975) and its aftermath, including hyperinflation, food shortages, and widespread poverty.[1] Over 60% of the population lived below the national poverty line in the early 1990s, a legacy of war and economic isolation resulting from severe sanctions imposed by the USA and its allies, as well as the country’s own Soviet-style economic policies.[2] The centrally planned system stifled private enterprise, limited productivity, and deepened stagnation. In the early 1990s, Vietnam’s healthcare system had many difficulties. By 2012, 68.5% of people had health insurance, up from just 16% in 1992.[3],[4] Rapid post-reform industrialization increased environmental degradation, with industrial zones like Binh Duong generating 30% of national wastewater, reducing agricultural yields by 10% in affected areas.[5] CO2 emissions rose 300% since 2000, threatening long-term. Rural-urban disparities persist, with 70% of healthcare facilities in cities, leaving rural areas underserved. Social inequalities, particularly among ethnic minorities (50% below the poverty line in 2015 compared to 10% for the Kinh majority), and health funding gaps (5.9% of GDP in 2020, below the WHO’s 7% recommendation) challenge sustainability.[6] These challenges highlight the complex interplay of historical legacy, structural deficiencies, and the emergent negative externalities of rapid economic growth. Addressing these issues requires a nuanced approach that balances economic imperatives with social equity and environmental sustainability.

3. History of Vietnam Economic Development

The Doi Moi started in 1986, opened the market, brought in foreign direct investment (FDI), and encouraged private businesses. These changes are in line with development economics theories like Amartya Sen’s capability approach, which focuses on giving marginalized groups more opportunities; Theodore Schultz’s human capital theory, which links health and education to productivity; and Arthur Lewis’s dual-sector model, which says that labor moves from agriculture to industry. The Doi Moi approach, which started in 1986, significantly modified Vietnam’s economic diplomacy. Vietnam decided to create more commercial ties with trading partner countries other than its communist friends after realizing that the Soviet bloc was behind the West regarding technology.[7] This included joining ASEAN in 1995, establishing a trade pact with the US in 2000, and entering the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2007. These milestones were very important for bringing Vietnam into the global economy and giving its new businesses access to new markets.

3.1 Poverty Reduction

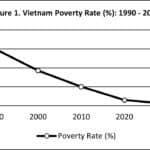

From 60% of the population lived in poverty in 1990, by 2020, poverty dropped to 6%, and extreme poverty reached 2% by 2023, driven by market reforms and targeted.[8] One of the most famous successes of Vietnam’s development journey is this amazing drop (Figure 1).

The National Target Program for Poverty Reduction focused on improving infrastructure in rural areas. This led to a 30% increase in rice yields in the Mekong Delta from 1990 to 2000 and made it possible for handcraft businesses to grow in the north.[9] This change in farming, along with changes to land ownership, gave smallholder farmers more authority and made a big difference in food security and income creation.

Microfinance is very important in Vietnam for giving women power and lowering poverty. By 2020, women had received 60% of the $10 billion in microloans. Women’s unions often carry out these programs, which have been good for both legal and economic empowerment.[10] The focus on women in microfinance programs is a deliberate attempt to close the gender gap and make the most of women’s economic potential. Conditional cash transfers from Program 135 built 200 schools in Lao Cai, which led to a 40% increase in H’mong enrollment.[11] These targeted interventions for ethnic minorities, while showing positive results, still face challenges in bridging the persistent gap in living standards between ethnic minority groups and the Kinh majority. Decentralized governance tailored interventions, such as coffee cultivation in the Central Highlands, reducing market access time by 50% in Quang Nam.[12] This localized approach allowed for greater responsiveness to specific regional needs and facilitated more effective resource allocation.

3.2. Public Health Reforms

With the help of financial incentives and government-led changes, the nation’s health insurance coverage increased from 16% in 1992 to 90% by 2020.[13] Vietnam’s commitment to the public good has been based on increasing health insurance coverage. By 2015, vaccination campaigns had reached 95% of people with measles and polio. The rates of death for mothers and babies have gone down a lot by 2019.[14] For instance, Since 1990, Vietnam has achieved impressive strides in lowering child mortality rates. Between 1990 and 2009, the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) fell from 58.0 to 24.5 per 1,000 live births, and the infant mortality rate (IMR) fell from 44.4 to 16.0 per 1,000 live births.[15] The Global Fund’s $500 million (2003–2020) and mobile clinics in Ha Giang, serving 80% of pregnant women, reduced neonatal mortality by 25%.[16] These international partnerships and grassroots initiatives highlight the multi-pronged approach to health improvement. However, chronic diseases like diabetes affect 10% of adults, straining capacity.[17] The healthcare system is facing new problems as the epidemiological trend shifts from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases. This means that the system needs to focus more on preventative care and long-term disease management. The fact that there are more healthcare facilities in cities than in rural and mountainous locations makes health disparities worse.

3.3. GDP Growth and Economic Transformation

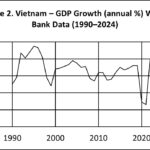

Vietnam’s GDP grew 6-7% annually, reaching $408 billion in 2022, with exports rising from $5 billion in 1990) to $371 billion in 2022.[18] This sustained high growth rate has propelled Vietnam into the ranks of lower-middle-income countries. FDI ($28 billion by 2020) drove manufacturing, with electronics (e.g., Samsung in Bac Ninh) and textiles employing millions.[19] The manufacturing sector, particularly in electronics, has become a key engine of growth, attracting significant foreign investment and creating numerous employment opportunities. For example, thanks to its dominance in Vietnamese industrial parks, Samsung has been able to escape the labor market issues in China, including the lack of skilled workers.[20] The company’s strategic investments have attracted foreign investors and helped Vietnam’s GDP rise.[21] Notably, 20% of Vietnam’s total exports are cellphones, which helps the country close its trade deficit.[22] Since 1990, Vietnam’s agricultural industry has experienced substantial change, consistent with Lewis’s structural change model. Between 1990 and 2020, the sector’s GDP share decreased from 38% to 12%, indicating a move toward manufacturing and services.[23] A successful economic development is marked by this change in structure, from an economy based on farming to one that is more and more based on industry and services. Kuznets’ curve shows that environmental costs are rising, which is why green technology like Hanoi’s waste-to-energy facilities are needed.[24] Numerous studies have supported the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory, which suggests an inverse U-shaped link between economic expansion and environmental degradation. At the provincial level in Vietnam, there are evidences in favor of the EKC, highlighting the contribution of green governance to the acceleration of environmental gains.[25] The environmental effects of economic expansion, such as air and water pollution, deforestation, and greenhouse gas emissions, are major risks to long-term sustainability, even while the growth itself has been outstanding. Vietnam’s CO2 emissions have gone up significantly because of more energy use for a growing economy.[26]

Since Doi Moi, Vietnam GDP per capita has grown significantly, lifting two third of its population out of poverty. Today, Vietnam GDP per capita is USD 4,717, according to World Bank Open Data.[27] Average GDP annual growth rate is 6,67% from 1990-2024.[28] (Figure 2)

3.4. Socialeconomic Advances

Over the past few decades, Vietnam has made notable strides in literacy and education. Between 1990 and 2015, the percentage of people aged 15 and over who were literate rose from 83% to over 95%.[29] Investment in human capital, particularly in technical and vocational education, has been crucial in meeting the demands of a rapidly industrializing economy. Female labor participation reached 73%, and social security covered 35% of workers by 2020.[30] Vietnam has kept a high number of women working for a number of reasons. Women have better job chances because of economic integration, especially with high-income countries has helped the economy grow significantly.[31] The growth of social security, even with its flaws, is an important safety net for an increasing number of workers. Vietnam’s National Green Growth Strategy uses renewable energy to lessen the effects of climate change and encourage long-term growth. The plan stipulates that by 2030, 47% of energy should come from renewable sources. This will help cut down on greenhouse gas emissions and energy utilization.[32] By 2030, Vietnam could provide 17% of its energy from renewable sources, but its rising energy needs will probably result in more coal use and CO2 emissions.[33] Small hydropower, wind, biomass, solar, geothermal, and tidal are examples of renewable energy sources in Vietnam.[34] Vietnam has a lot of potential for renewable energy, but it has some problems that make it hard to develop. These include a lack of adequate socioeconomic and environmental impact studies, limited infrastructure, and inconsistent rules. Vietnam’s ambitious goals show that the country is serious about moving toward a more environmentally friendly and sustainable economy. To lessen the environmental effects of fast industrialization, it is important to foster green growth by investing in renewable energy and using the concepts of a circular economy. But to make its growth better and help Vietnam’s long-term future, more research and effective solutions are needed to deal with the problems of using renewable energy for green growth.[35]

3.5. Economic Diplomacy: The Balancing Acts

The Doi Moi (Reforms) that started in 1986 changed Vietnam’s economy in a big way. They made it more market-oriented and opened the country to trade and foreign investment. Vietnam has had to make this significant transformation because the economy is stuck, and now they are looking for alliances with the world’s biggest countries, like the US and China. After the Vietnam War, things between the US and Vietnam stayed tense for many years. Vietnam’s foreign policy changed significantly in 1995 when this disagreement led to the acceptance of bilateral ties. The 2001 US-Vietnam bilateral commercial agreement made Vietnam’s Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) feasible, further strengthening this trend.[36] By 2013, the US and Vietnam had built a global connection that showed they were committed to enhancing economic links, working together to keep people secure, and keeping the area stable.[37] As a result, trade with the United States has increased, making it one of Vietnam’s most important export markets and a key foreign direct investment (FDI) source. However, this economic commitment was carefully weighed against Vietnam’s long-standing historical, cultural, and financial ties to China, which has been its most important trading partner and ideological friend for a long time.[38] China’s economic rise toward the end of the 20th century created opportunities and problems for Vietnam. Deep historical ties and an intricate web of trade, geography, and political links connect the two countries.

Vietnam is trying to get the most out of its diplomatic and economic initiatives while protecting its sovereignty in the face of rising trade tensions between the US and China. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stresses that Vietnam is dedicated to being a dependable partner for peace and development worldwide.[39] Vietnam strengthens its ties with other regional economies, boosts its global negotiating power, and supports its growth through exports by participating in multilateral trade agreements like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).[40] These agreements lower tariffs and make trade rules easier to follow. Vietnam also diversifies its economic partnerships by strengthening its ties with Japan and South Korea. This brings in foreign direct investment (FDI), which helps with technology transfer and building local skills. Japan’s significant investments in manufacturing and infrastructure, made possible by the Vietnam-Japan economic cooperation pact, show how important Vietnam is to Southeast Asia.[41] The Vietnam-Korea Free Trade Agreement (VKFTA) helps South Korea’s investments build similar electronics and textiles industries. Companies like Intel and Samsung have made significant investments in Vietnam, showing the attractiveness of its manufacturing base. Samsung is the most important contributor to foreign direct investment (FDI).[42] Vietnam’s participation in Free Trade Agreements like the CPTPP and EVFTA aligns it with global economic standards, making it more appealing to investors, especially from the EU, and encouraging long-term economic practices. Vietnam is becoming more resilient and independent by doing these things. It is also diversifying its economic links to better deal with the US-China conflict.

- Recommendation

Vietnam has made great progress, but it still has problems that need long-term, strategic solutions. Some of these are ongoing differences between regions, especially between cities and rural areas and between different ethnic groups; environmental damage caused by rapid industrialization; and the need to make social safety nets even stronger.

4.1. Equitable Resouces Allocation

To fix the problems that are still there, Vietnam should focus on fair resource distribution, especially in rural health and education. This would mean hiring more qualified doctors and teachers in locations that don’t have enough of them, improving the infrastructure of schools and health clinics, and offering incentives to draw and keep talented people in these areas. For example, specific targets could be set to reduce the doctor-to-population ratio in rural areas from the current national average of 8 doctors per 10,000 people to at least 15 doctors per 10,000 in priority rural provinces by 2035, according to the Ministry of Health.[43] Similarly, giving more scholarships and training programs to students from ethnic minority groups who want to work in health and education could help with both professional shortages and social inequality.

4.2. Public Private Partnerships and Green Infrastructure

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are a good way to pay for necessary healthcare and green infrastructure projects that will create many jobs. Vietnam might learn from Singapore’s effective waste management systems and Thailand’s successful hospital modernization programs, which used public-private partnerships well. For example, setting up a national PPP framework with clear rules and incentives for private sector participation might bring in money from both inside and outside the country for initiatives like renewable energy, innovative grid development, and building infrastructure that will last. Vietnam works hard to use green growth methods to fight climate change and promote long-term development. The country seeks to create green jobs as part of the National Green Growth Strategy for 2021–2030. Research shows that human capital helps green jobs expand. Right now, 15% of Vietnamese workers are in green jobs.[44] Also, PPPs could be utilized to create specialized healthcare facilities, such homes for the elderly or rehabilitation centers, to meet the needs of the Vietnamese population as they change.

4.3. Scaling Telemedicine and Rural Healthcare Accesses

Telemedicine has shown great promise as a healthcare model in Vietnam, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. High user satisfaction ratings have been found in studies that show how well it monitors patients with high blood pressure in Binh Duong province.[45] With an emphasis on doctor-to-doctor contact, the deployment of telehealth systems at Phu Tho General Hospital has demonstrated benefits in healthcare outcomes. A recent study at the Polyclinic of Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine found that there is a high demand for telemedicine consultations, especially in the fields of psychology and dermatology.[46] These pilot projects have improved remote patient care and facilitated communication between patients and healthcare providers by utilizing various technologies, such as cloud-based platforms, smartphone applications, and blood pressure monitoring devices. To make this program available across the country, we would need to improve digital infrastructure in rural regions, teach healthcare workers how to use telemedicine technologies, and create clear rules to make sure that everyone had access to quality care. The expansion might involve giving money to remote patients so they can use telemedicine services, making sure that cost doesn’t get in the way. This kind of development could make it easier for people in rural areas to get care by cutting down on the need for them to drive large distances for appointments. This would also lower healthcare expenditures for rural households.

4.4. Strengthen Social Safety Nets and Just Transition

It is also important to improve social safety nets so that workers affected by economic restructuring, especially in the agriculture sector, can have a Just Transition. This can be done by raising unemployment compensation and offering retraining programs. Vietnam’s industrialization and urbanization have resulted in a large-scale conversion of agricultural land, affecting farmers’ employment and lives.[47] Traditional farming livelihoods have been affected by land loss brought on by these processes, requiring farmers to modify their approaches. Many farmers may lose their jobs if Vietnam continues to industrialize and move people to cities. Comprehensive social security programs, such as unemployment insurance, vocational training, and job placement services, can help people and communities affected by the changes by making it easier for them to find work and get back on their feet.[48] This aligns with the ideas behind inclusive growth, meaning that development benefits are spread widely across society. Also, social assistance programs that help specific ethnic minority groups that are more likely to be poor need to be improved to bridge the gaps in fairness that already exists.

4.5. International Cooperation and Sustainable Development Practices

Leveraging international cooperation is vital for scaling up renewable energy initiatives and promoting sustainable industrial practices. Vietnam may secure substantial financing, including $1.5 billion from the Green Climate Fund, to expedite its transition to a low-carbon economy.[49] Leveraging ASEAN’s expertise and best practices in sustainable development, such as Thailand’s eco-industrial zones, can foster knowledge sharing and regional cooperation. This involves participating in global conferences, forging agreements with other nations to exchange technology, and collaborating on regional projects to drive long-term progress. Trade agreements should explicitly mandate environmentally friendly practices from foreign direct investment (FDI) companies, ensuring that foreign investments align with Vietnam’s environmental goals rather than undermining them. International labor and environmental standards emphasize that robust environmental impact assessments and accountability mechanisms are critical to achieving this. By embedding sustainability into its economic diplomacy, Vietnam can attract responsible investors and strengthen its reputation as a leader in green growth.

4.6. Economic Diplomacy

Vietnam utilizes a well-planned strategy based on its long-standing diplomatic principle of “Four No’s” to deal with these problems and challenges.[50] No military bases in other countries, no ties between nations, no military alliances, and no use of force. This theory shows that Vietnam wants to keep some level of independence in its relations with other countries. This lets it build diplomatic and economic ties without aligning with significant power. Vietnam actively participates in multilateral organizations such as ASEAN, the Regional Economic Partnership (RCEP), and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to strengthen its sovereignty.[51] This diversification makes Vietnam’s economy more independent and able to handle geopolitical upheaval.

Vietnam’s strategic diplomacy, rooted in a historical commitment to non-alignment, has effectively protected national interests and driven economic growth while maintaining independence in an increasingly fragmented world.[52]

Vietnam’s foreign policy to China is flexible and forward-thinking because it carefully balances the goals of both China and the United States. Study of Fatharani (2022) shows how dangerous it may be to rely on only one side, which is why the holistic approach to Vietnam is so interesting.[53] Vietnam has discovered a way to stabilize its economy by using its historical ties to other economies and its geographic proximity to vital trade routes. This is achieved by expanding its corporate alliances and actively seeking international investments.

Vietnam has been proactively aligning its policies to keep up with the changing nature of global trade. Its strategic coastal location and proximity to major shipping routes will strengthen its position as a key industrial and logistical hub. At the same time, it will keep an eye on geopolitical changes caused by the growing importance of emerging markets. With infrastructure, education, and innovation investments, Vietnam’s competitive edge will grow even further. This will make it an essential part of future global supply chains. Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh of Vietnam and Prime Minister Christopher Luxon of New Zealand announced a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership on February 26, 2025. Similar agreements were made with Indonesia and Singapore on March 11-12, 2025, during General Secretary To Lam’s visits to President Prabowo Subianto and Prime Minister Lawrence Wong. These were Vietnam’s 11th and 12th such partnerships. These achievements build on the 2023 Vietnam-Australia Comprehensive Strategic Partnership and show how well Vietnam can navigate the changing global economy and politics. The Vietnamese government is creating a strong basis for a knowledge-based economy by prioritizing digital infrastructure, artificial intelligence, and innovation ecosystems. This will make Vietnam a dynamic middle power in the world arena.

- Conclusion

Vietnam’s rise from a war-torn, poor country to a dynamic, market-based economy shows how powerful strategic reforms and economic diplomacy can be. The Doi Moi reforms of 1986 led to amazing progress in reducing poverty, improving public health, increasing GDP, and making social progress, making Vietnam an example for other emerging countries. Trade agreements and foreign direct investment have helped the country become part of the global economy, which has contributed to steady economic progress. Targeted programs like microfinance and health insurance expansion have also helped millions of people. But problems like differences between rural and urban areas, environmental damage, and socioeconomic inequality among ethnic minorities show how important it is to have long-term, inclusive plans. Vietnam can tackle these problems while promoting sustainable development by putting a high priority on fair resource distribution, expanding telemedicine, encouraging partnerships between the public and private sectors, enhancing social safety nets, and making the most of international cooperation. With an excellent, balanced diplomacy strategy, Vietnam ensures that its economic growth continues to benefit society as a whole, securing a strong and equitable future for all its residents.

6. Conflict of Interest

The author states that there is no conflict of interest.

7. Acknowledgment

I acknowledge all the support from Euclid University.

References

Baum, Anja. ‘Vietnam’s Development Success Story and the Unfinished SDG Agenda’. IMF. Accessed 15 July 2025. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/02/14/Vietnam-s-Development-Success-Story-and-the-Unfinished-SDG-Agenda-48966.

Dang, Hai-Anh H., Klaus Deininger, and Viet Cuong Nguyen. ‘Did Program Support for the Poorest Areas Work? Evidence from Rural Vietnam’. Accessed 15 July 2025. https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/17445/did-program-support-for-the-poorest-areas-work-evidence-from-rural-vietnam.

Dang, Hai-Anh H., Shatakshee Dhongde, Minh N. N. Do, Cuong Viet Nguyen, and Obert Pimhidzai. ‘Rapid Economic Growth but Rising Poverty Segregation: Will Vietnam Meet the SDGs for Equitable Development?’ Review of Development Economics n/a, no. n/a (forthcoming). https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.13175.

Do, Thi Thu. ‘Green growth in Vietnam: Current status and policy implications’. 2025. https://tapchitckt.hvtc.edu.vn/tabid/1631/baibao/406/title/green-growth-in-vietnam-current-status-and-policy-implications/Default.aspx.

Dung, Vu Xuan, and Duong Thuy Le. ‘The Relationship between Government Spending and Poverty Alleviation in Emerging Markets: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam’. Asian Affairs: An American Review 50, no. 4 (2023): 276–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/00927678.2023.2262355.

Fatharani, Fitri. ‘Analysis of Vietnam’s Response to the US-China Trade War in Times of Pandemic’. Atlantis Press, 24 December 2022, 720–30. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-65-7_58.

Hai Anh, Nguyen, and Nguyen Cao Ha Trang. ‘The Impact of Human Capital on Green Job Growth in Vietnam’. International Journal of Social Science & Economic Research 09, no. 03 (2024): 753–70. https://doi.org/10.46609/ijsser.2024.v09i03.007.

Hoang, Trieu-Hoa, Ba-Tam Le, Thi-Thanh-Xuan Mai, and Thi-Linh Pham. ‘Green Governance and the EKC Hypothesis: Evidence from Vietnamese Provinces’. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 8, no. 6 (2024): 6. https://doi.org/10.55214/25768484.v8i6.2686.

Hoang, Van Minh, Juhwan Oh, Tuan Anh Tran, et al. ‘Patterns of Health Expenditures and Financial Protections in Vietnam 1992-2012’. Journal of Korean Medical Science 30, no. Suppl 2 (2015): S134–38. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.S2.S134.

Ke, Zhihao. ‘Climate Shocks in Vietnam, Agriculture, Migration, and Structural Transformation’. Applied and Computational Engineering 136 (March 2025): 100–105. https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/2025.21320.

Kozlov, Vyacheslav A., Osor R. Ochirov, Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, et al. ‘THE ROLE OF SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS VIETNAM CO. IN THE VIETNAMESE ECONOMY’. EKONOMIKA I UPRAVLENIE: PROBLEMY, RESHENIYA 4/3, no. 124 (2022): 120–32. https://doi.org/10.36871/ek.up.p.r.2022.04.03.010.

Lim, Sunghun, and Anh Phuoc Thien Nguyen. ‘Shifting Trade Winds: Southeast Asia’s Response to the United States–People’s Republic of China Trade Dispute’. Asian Development Review 41, no. 02 (2024): 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0116110524400134.

M, Oh, Jung Eun,Mtonya,Brian G. ,Kunaka,Charles,Lebrand,Mathilde Sylvie Maria,Pimhidzai,Obert,Ð?c, Ph?m Minh,Skorzus,Roman Constantin,Jaffee,Steven. ‘Vietnam Development Report 2019 : Connecting Vietnam for Growth and Shared Prosperity’. Text/HTML. World Bank. Accessed 15 July 2025. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/en/590451578409008253.

Mao, Wenhui, Yuchen Tang, Tra Tran, Michelle Pender, Phuong Nguyen Khanh, and Shenglan Tang. ‘Advancing Universal Health Coverage in China and Vietnam: Lessons for Other Countries’. BMC Public Health 20, no. 1 (2020): 1791. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09925-6.

Meessen, Jérôme, Claude Croizer, and P. Verlé. ‘The Vietnam Green Growth Strategy: A Review of Specificities, Indicators and Research Perspectives’. 2015. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Viet-Nam-Green-Growth-Strategy%3A-A-review-of-and-Meessen-Croizer/6637d7b411cfd3c1f4d0687108106860d8b4b79b.

Nakamura, Haruhiko, and Tomoo Marukawa. ‘How Can the Value Added of Vietnam’s Export Industries Be Increased?’ The Japanese Political Economy 50, no. 2 (2024): 120–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/2329194X.2024.2331531.

Narayan, Seema Wati, Tri Tung Nguyen, and Xuan-Hoa Nghiem. ‘Does Ecoconomic Integration Increase Female Labour Force Participation? Some New Evidence From Vietnam’. Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking 24, no. 1 (2021): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.21098/bemp.v24i1.1577.

Nguyen, D. Hinh, and Van Minh Hoang. ‘Guest Editorial: Public Health in Vietnam: Scientific Evidence for Policy Changes and Interventions’. Global Health Action 6, no. 1 (2013): 20443. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.20443.

Nguyen, Q. ‘Long Term Optimization of Energy Supply and Demand in Vietnam with Special Reference to the Potential of Renewable Energy’. 2005. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Long-term-optimization-of-energy-supply-and-demand-Nguyen/03f031d031ae359a7b4ed9e03e3c520e291006c1.

Path, Kosal. ‘The Origins and Evolution of Vietnam’s Doi Moi Foreign Policy of 1986’. TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 8, no. 2 (2020): 171–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2020.3.

Phan, Thi Thanh Nhan, Zsuzsanna Plank, and Levente Hufnagel. ‘A Scientific Review on the Issues of Sustainability in Vietnam During the Period from 2011 to 2021 | IIETA’. 2024. https://doi.org/10.18280/ijsdp.190404.

Phu, Vien Vinh, Do Minh Thai, Nguyen Le Thanh An, Tran Ngoc Viet, Nguyen Phuong Nam, and Vo Van Toi. ‘Efficiency Evaluation of a Pilot Telemedicine System to Monitor High Blood Pressures in Binh Duong Province (Vietnam)’. In 8th International Conference on the Development of Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam, edited by Vo Van Toi, Thi-Hiep Nguyen, Vong Binh Long, and Ha Thi Thanh Huong. Springer International Publishing, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75506-5_21.

Pietrasiak, Małgorzata. ‘Vietnam Game Between USA and China’. International Studies. Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal 22, no. 1 (2018): 1. https://doi.org/10.18778/1641-4233.22.04.

Quan, Nguyen K., and Andrew W. Taylor-Robinson. ‘Vietnam’s Evolving Healthcare System: Notable Successes and Significant Challenges’. Cureus 15, no. 6 (2023): e40414. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.40414.

Raihan, Asif, Md. Atik Hasan, Liton Chandra Voumik, Dulal Chandra Pattak, Salma Akter, and Mohammad Ridwan. ‘Sustainability in Vietnam: Examining Economic Growth, Energy, Innovation, Agriculture, and Forests’ Impact on CO2 Emissions’. World Development Sustainability 4 (June 2024): 100164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wds.2024.100164.

Ron, Aviva, Guy Carrin, and Tran Van Tien. ‘Viet Nam: The Development of National Health Insurance’. International Social Security Review 51, no. 3 (1998): 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-246X.00018.

Sheldon, Peter, and Seung-Ho Kwon. ‘Samsung in Vietnam: FDI, Business–Government Relations, Industrial Parks, and Skills Shortages’. The Economic and Labour Relations Review 34, no. 1 (2023): 66–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/elr.2022.3.

Suu, Nguyen Van. Agricultural Land Conversion and Its Effects on Farmers in Contemporary Vietnam. Focaal. 1 June 2009. https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2009.540109.

Tạp chí Cộng sản. ‘Việt Nam không tham gia liên minh quân sự là chính sách quốc phòng đúng đắn’. Tạp chí Cộng sản. Accessed 5 March 2025. https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/media-story/-/asset_publisher/V8hhp4dK31Gf/content/viet-nam-khong-tham-gia-lien-minh-quan-su-la-chinh-sach-quoc-phong-dung-dan.

Thắng Nguyễn Trần Minh, Sang Trương Tiến, Hoàng Nguyễn Văn, et al. ‘Thực trạng sử dụng dịch vụ tư vấn y tế từ xa tại Phòng khám Đa khoa trường Đại học Y khoa Phạm Ngọc Thạch năm 2021 – 2022’: Tạp chí Y Dược học Phạm Ngọc Thạch 2, no. 1 (2023): 1.

Thanh, Long Bui, Lucía Morales, and Bernadette Andreosso-O’Callaghan. ‘The Role of Microfinance in Women Empowerment: Global Sustainable Perspectives in the Case of Vietnam’. In Sustainable Development and Energy Transition in Europe and Asia. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119705222.ch1.

The White House. ‘Joint Statement by President Barack Obama of the United States of America and President Truong Tan Sang of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam’. Whitehouse.Gov, 25 July 2013. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/25/joint-statement-president-barack-obama-united-states-america-and-preside.

Tran, Ha Ninh. ‘Renewable Energy in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) of Vietnam’. In Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Local Development and Techno-Economic Aspects, edited by Hoy-Yen Chan and Kamaruzzaman Sopian. Springer International Publishing, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89809-4_3.

Trinh, Nguyễn Võ Hoàng. ‘Geoeconomic and Foreign Policy Implications of Vietnam’s Economic Dependence on China’. Trường Chính sách công và Quản lý Fulbright, Đại học Fulbright Việt Nam, 2024. https://dlib.fulbright.edu.vn/handle/123456789/841.

Tu, Thuy Anh, Ты Тхюи Ань, Thi Mai Phuong Chu, Тю Тхи Май Фыонг, Thi Lan Huong Truong, and Чыонг Тхи Лан Хыонг. ‘Impacts of the US-China Trade Tension and RCEP on Vietnam-China Trade Balance’. The Russian Journal of Vietnamese Studies 8, no. 1 (2024): 1. https://doi.org/10.54631/VS.2024.81-626487.

Tung, Le T. ‘Role of Unemployment Insurance in Sustainable Development in Vietnam: Overview and Policy Implication’. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 6, no. 3 (2019): 1139–55. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.6.3(6).

Van Can, Luc, and Tu Ngoc Dang. ‘Challenges in Searching for Vietnam’s Growth Drivers Through 2030’. Asian Economic Policy Review 19, no. 2 (2024): 252–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12458.

Van Minh, Hoang, and Philip Nasca. ‘Public Health in Transitional Vietnam: Achievements and Challenges’. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 24 (April 2018): S1. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000759.

Vietnam MOFA. ‘- Chính sách đối ngoại của Việt Nam trong giai đoạn hiện nay’. MLNews. Accessed 8 March 2025. https://www.mofa.gov.vn/vi/cs_doingoai/cs/ns040823163300.

Vietnam, U. S. Mission. ‘The U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) – Resources for Understanding’. U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam, 27 June 2020. https://vn.usembassy.gov/the-u-s-vietnam-bilateral-trade-agreement-bta-resources-for-understanding/.

Vinh, Hoang Xuan, Luu Huu Van, Nguyen The Vinh, et al. ‘Middle-Income Traps: Experiences of Asian Countries and Lessons for Vietnam’. Multidisciplinary Reviews 7, no. 5 (2024): 2024100–2024100. https://doi.org/10.31893/multirev.2024100.

VnExpress. ‘Vietnam Aims for 15 Doctors per 10,000 People by 2025 – VnExpress International’. VnExpress International – Latest News, Business, Travel and Analysis from Vietnam, 2024. https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-aims-for-15-doctors-per-10-000-people-by-2025-4716651.html.

Vu, Van-Hoa, Jenn-Jaw Soong, and Khac-Nghia Nguyen. ‘The Political Economy of Vietnam and Its Development Strategy under China–USA Power Rivalry and Hegemonic Competition: Hedging for Survival’. The Chinese Economy 56, no. 4 (2023): 256–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2022.2136690.

World Bank. ‘GDP Growth Annual (Vietnam)’. World Bank Open Data. Accessed 12 August 2025. https://data.worldbank.org.

World Bank. ‘GDP per Capita (Current US$) – Viet Nam’. World Bank Open Data. Accessed 12 August 2025. https://data.worldbank.org.

World Bank. ‘Publication: Accelerating Clean, Green, and Climate-Resilient Growth in Vietnam: A Country Environmental Analysis’. 2022. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/b11c8c18-f440-56f7-aa24-4557a71376fc.

World Bank. ‘Vietnam’s Economy Forecast to Grow by 6.3% in 2023, World Bank Report Says’. Text/HTML. World Bank. Accessed 15 July 2025. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/03/13/vietnam-s-economy-forecast-to-grow-by-6-3-in-2023-world-bank-report-says.

Zitelmann, Rainer. How Nations Escape Poverty: Vietnam, Poland, and the Origins of Prosperity. Encounter Books, 2024.

[1] Anja Baum, ‘Vietnam’s Development Success Story and the Unfinished SDG Agenda’, IMF, accessed 15 July 2025, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/02/14/Vietnam-s-Development-Success-Story-and-the-Unfinished-SDG-Agenda-48966.

[2] Oh M Jung Eun,Mtonya,Brian G. ,Kunaka,Charles,Lebrand,Mathilde Sylvie Maria,Pimhidzai,Obert,Ð?c, Ph?m Minh,Skorzus,Roman Constantin,Jaffee,Steven, ‘Vietnam Development Report 2019 : Connecting Vietnam for Growth and Shared Prosperity’, Text/HTML, World Bank, accessed 15 July 2025, https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/en/590451578409008253.

[3] Van Minh Hoang et al., ‘Patterns of Health Expenditures and Financial Protections in Vietnam 1992-2012’, Journal of Korean Medical Science 30, no. Suppl 2 (2015): S134–38, https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2015.30.S2.S134.

[4] Aviva Ron et al., ‘Viet Nam: The Development of National Health Insurance’, International Social Security Review 51, no. 3 (1998): 89–103, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-246X.00018.

[5] Thi Thanh Nhan Phan et al., ‘A Scientific Review on the Issues of Sustainability in Vietnam During the Period from 2011 to 2021 | IIETA’, 2024, https://doi.org/10.18280/ijsdp.190404.

[6] Hai-Anh H. Dang et al., ‘Rapid Economic Growth but Rising Poverty Segregation: Will Vietnam Meet the SDGs for Equitable Development?’, Review of Development Economics n/a, no. n/a (forthcoming), https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.13175.

[7] Kosal Path, ‘The Origins and Evolution of Vietnam’s Doi Moi Foreign Policy of 1986’, TRaNS: Trans-Regional and -National Studies of Southeast Asia 8, no. 2 (2020): 171–85, https://doi.org/10.1017/trn.2020.3.

[8] Hoang Xuan Vinh et al., ‘Middle-Income Traps: Experiences of Asian Countries and Lessons for Vietnam’, Multidisciplinary Reviews 7, no. 5 (2024): 2024100–2024100, https://doi.org/10.31893/multirev.2024100.

[9] Vu Xuan Dung and Duong Thuy Le, ‘The Relationship between Government Spending and Poverty Alleviation in Emerging Markets: Empirical Evidence from Vietnam’, Asian Affairs: An American Review 50, no. 4 (2023): 276–303, https://doi.org/10.1080/00927678.2023.2262355.

[10] Long Bui Thanh et al., ‘The Role of Microfinance in Women Empowerment: Global Sustainable Perspectives in the Case of Vietnam’, in Sustainable Development and Energy Transition in Europe and Asia (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119705222.ch1.

[11] Hai-Anh H. Dang et al., ‘Did Program Support for the Poorest Areas Work? Evidence from Rural Vietnam’, accessed 15 July 2025, https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/17445/did-program-support-for-the-poorest-areas-work-evidence-from-rural-vietnam.

[12] Dung and Le, ‘The Relationship between Government Spending and Poverty Alleviation in Emerging Markets’, 290.

[13] Wenhui Mao et al., ‘Advancing Universal Health Coverage in China and Vietnam: Lessons for Other Countries’, BMC Public Health 20, no. 1 (2020): 1791, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09925-6.

[14] Nguyen K. Quan and Andrew W. Taylor-Robinson, ‘Vietnam’s Evolving Healthcare System: Notable Successes and Significant Challenges’, Cureus 15, no. 6 (2023): e40414, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.40414.

[15] D. Hinh Nguyen and Van Minh Hoang, ‘Guest Editorial: Public Health in Vietnam: Scientific Evidence for Policy Changes and Interventions’, Global Health Action 6, no. 1 (2013): 20443, https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v6i0.20443.

[16] Quan and Taylor-Robinson, ‘Vietnam’s Evolving Healthcare System’.

[17] Phan et al., ‘A Scientific Review on the Issues of Sustainability in Vietnam During the Period from 2011 to 2021 | IIETA’.

[18] World Bank, ‘Vietnam’s Economy Forecast to Grow by 6.3% in 2023, World Bank Report Says’, Text/HTML, World Bank, accessed 15 July 2025, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2023/03/13/vietnam-s-economy-forecast-to-grow-by-6-3-in-2023-world-bank-report-says.

[19] Luc Van Can and Tu Ngoc Dang, ‘Challenges in Searching for Vietnam’s Growth Drivers Through 2030’, Asian Economic Policy Review 19, no. 2 (2024): 252–67, https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12458.

[20] Peter Sheldon and Seung-Ho Kwon, ‘Samsung in Vietnam: FDI, Business–Government Relations, Industrial Parks, and Skills Shortages’, The Economic and Labour Relations Review 34, no. 1 (2023): 66–85, https://doi.org/10.1017/elr.2022.3.

[21] Vyacheslav A. Kozlov et al., ‘The role of SamSung Electronic Vietnam Co. In the Vietnamese Economy’, EKONOMIKA I UPRAVLENIE: PROBLEMY, RESHENIYA 4/3, no. 124 (2022): 120–32, https://doi.org/10.36871/ek.up.p.r.2022.04.03.010.

[22] Haruhiko Nakamura and Tomoo Marukawa, ‘How Can the Value Added of Vietnam’s Export Industries Be Increased?’, The Japanese Political Economy 50, no. 2 (2024): 120–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/2329194X.2024.2331531.

[23] Zhihao Ke, ‘Climate Shocks in Vietnam, Agriculture, Migration, and Structural Transformation’, Applied and Computational Engineering 136 (March 2025): 100–105, https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/2025.21320.

[24] Phan et al., ‘A Scientific Review on the Issues of Sustainability in Vietnam During the Period from 2011 to 2021 | IIETA’.

[25] Trieu-Hoa Hoang et al., ‘Green Governance and the EKC Hypothesis: Evidence from Vietnamese Provinces’, Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology 8, no. 6 (2024): 6, https://doi.org/10.55214/25768484.v8i6.2686.

[26] Asif Raihan et al., ‘Sustainability in Vietnam: Examining Economic Growth, Energy, Innovation, Agriculture, and Forests’ Impact on CO2 Emissions’, World Development Sustainability 4 (June 2024): 100164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wds.2024.100164.

[27] World Bank, ‘GDP per Capita (Current US$) – Viet Nam’, World Bank Open Data, accessed 12 August 2025, https://data.worldbank.org.

[28] World Bank, ‘GDP Growth Annual (Vietnam)’, World Bank Open Data, accessed 12 August 2025, https://data.worldbank.org.

[29] Hoang Van Minh and Philip Nasca, ‘Public Health in Transitional Vietnam: Achievements and Challenges’, Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 24 (April 2018): S1, https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000000759.

[30] Rainer Zitelmann, How Nations Escape Poverty: Vietnam, Poland, and the Origins of Prosperity (Encounter Books, 2024).

[31] Seema Wati Narayan et al., ‘Does Ecoconomic Integration Increase Female Labour Force Participation? Some New Evidence From Vietnam’, Bulletin of Monetary Economics and Banking 24, no. 1 (2021): 1–34, https://doi.org/10.21098/bemp.v24i1.1577.

[32] Thi Thu Do, ‘Green growth in Vietnam: Current status and policy implications’, 2025, https://tapchitckt.hvtc.edu.vn/tabid/1631/baibao/406/title/green-growth-in-vietnam-current-status-and-policy-implications/Default.aspx.

[33] Q. Nguyen, ‘Long Term Optimization of Energy Supply and Demand in Vietnam with Special Reference to the Potential of Renewable Energy’, 2005, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Long-term-optimization-of-energy-supply-and-demand-Nguyen/03f031d031ae359a7b4ed9e03e3c520e291006c1.

[34] Ha Ninh Tran, ‘Renewable Energy in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) of Vietnam’, in Renewable Energy in Developing Countries: Local Development and Techno-Economic Aspects, ed. Hoy-Yen Chan and Kamaruzzaman Sopian (Springer International Publishing, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89809-4_3.

[35] Jérôme Meessen et al., ‘The Vietnam Green Growth Strategy: A Review of Specificities, Indicators and Research Perspectives’, 2015, https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Viet-Nam-Green-Growth-Strategy%3A-A-review-of-and-Meessen-Croizer/6637d7b411cfd3c1f4d0687108106860d8b4b79b.

[36] U. S. Mission Vietnam, ‘The U.S.-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement (BTA) – Resources for Understanding’, U.S. Embassy & Consulate in Vietnam, 27 June 2020, https://vn.usembassy.gov/the-u-s-vietnam-bilateral-trade-agreement-bta-resources-for-understanding/.

[37] The White House, ‘Joint Statement by President Barack Obama of the United States of America and President Truong Tan Sang of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam’, Whitehouse.Gov, 25 July 2013, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/07/25/joint-statement-president-barack-obama-united-states-america-and-preside.

[38] Małgorzata Pietrasiak, ‘Vietnam Game Between USA and China’, International Studies. Interdisciplinary Political and Cultural Journal 22, no. 1 (2018): 1, https://doi.org/10.18778/1641-4233.22.04.

[39] Vietnam MOFA, ‘- Chính sách đối ngoại của Việt Nam trong giai đoạn hiện nay’, MLNews, accessed 8 March 2025, https://www.mofa.gov.vn/vi/cs_doingoai/cs/ns040823163300.

[40] Thuy Anh Tu et al., ‘Impacts of the US-China Trade Tension and RCEP on Vietnam-China Trade Balance’, The Russian Journal of Vietnamese Studies 8, no. 1 (2024): 1, https://doi.org/10.54631/VS.2024.81-626487.

[41] Sunghun Lim and Anh Phuoc Thien Nguyen, ‘Shifting Trade Winds: Southeast Asia’s Response to the United States–People’s Republic of China Trade Dispute’, Asian Development Review 41, no. 02 (2024): 57–80, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0116110524400134.

[42] Sheldon and Kwon, ‘Samsung in Vietnam’.

[43] VnExpress, ‘Vietnam Aims for 15 Doctors per 10,000 People by 2025 – VnExpress International’, VnExpress International – Latest News, Business, Travel and Analysis from Vietnam, 2024, https://e.vnexpress.net/news/news/vietnam-aims-for-15-doctors-per-10-000-people-by-2025-4716651.html.

[44] Nguyen Hai Anh and Nguyen Cao Ha Trang, ‘The Impact of Human Capital on Green Job Growth in Vietnam’, International Journal of Social Science & Economic Research 09, no. 03 (2024): 753–70, https://doi.org/10.46609/ijsser.2024.v09i03.007.

[45] Vien Vinh Phu et al., ‘Efficiency Evaluation of a Pilot Telemedicine System to Monitor High Blood Pressures in Binh Duong Province (Vietnam)’, in 8th International Conference on the Development of Biomedical Engineering in Vietnam, ed. Vo Van Toi et al. (Springer International Publishing, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75506-5_21.

[46] Thắng Nguyễn Trần Minh et al., ‘Thực trạng sử dụng dịch vụ tư vấn y tế từ xa tại Phòng khám Đa khoa trường Đại học Y khoa Phạm Ngọc Thạch năm 2021 – 2022’:, Tạp chí Y Dược học Phạm Ngọc Thạch 2, no. 1 (2023): 1.

[47] Nguyen Van Suu, Agricultural Land Conversion and Its Effects on Farmers in Contemporary Vietnam, Focaal, 1 June 2009, https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2009.540109.

[48] Le T. Tung, ‘Role of Unemployment Insurance in Sustainable Development in Vietnam: Overview and Policy Implication’, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 6, no. 3 (2019): 1139–55, https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2019.6.3(6).

[49] World Bank, ‘Publication: Accelerating Clean, Green, and Climate-Resilient Growth in Vietnam: A Country Environmental Analysis’, 2022, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/b11c8c18-f440-56f7-aa24-4557a71376fc.

[50] Tạp chí Cộng sản, ‘Việt Nam không tham gia liên minh quân sự là chính sách quốc phòng đúng đắn’, Tạp chí Cộng sản, accessed 5 March 2025, https://tapchicongsan.org.vn/media-story/-/asset_publisher/V8hhp4dK31Gf/content/viet-nam-khong-tham-gia-lien-minh-quan-su-la-chinh-sach-quoc-phong-dung-dan.

[51] Nguyễn Võ Hoàng Trinh, ‘Geoeconomic and Foreign Policy Implications of Vietnam’s Economic Dependence on China’ (Trường Chính sách công và Quản lý Fulbright, Đại học Fulbright Việt Nam, 2024), https://dlib.fulbright.edu.vn/handle/123456789/841.

[52] Van-Hoa Vu et al., ‘The Political Economy of Vietnam and Its Development Strategy under China–USA Power Rivalry and Hegemonic Competition: Hedging for Survival’, The Chinese Economy 56, no. 4 (2023): 256–70, https://doi.org/10.1080/10971475.2022.2136690.

[53] Fitri Fatharani, ‘Analysis of Vietnam’s Response to the US-China Trade War in Times of Pandemic’, Atlantis Press, 24 December 2022, 720–30, https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-65-7_58.